Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

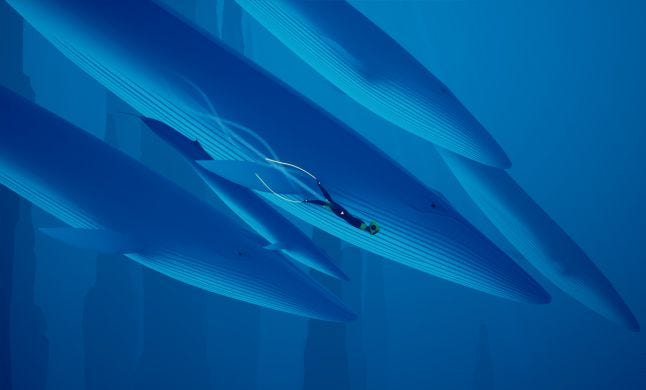

As Giant Squid releases Abzu, lead engineer Brian Balamut chats with Gamasutra about the practical challenges (and personal upsides) of making a chill nonviolent underwater exploration game.

Brian Balamut is a certified scuba diver.

That might never have happened if Balamut didn’t also happen to be a game developer, and the lead programmer on Giant Squid’s underwater diving game Abzu.

Out this week on PlayStation 4 and PC, Abzu is being pitched as a non-violent game about exploration (both external and internal) inspired by studio founder (and former Journey art director) Matt Nava’s time scuba diving.

It's less a realistic Scuba Simulator 2016 and more an attempt to convey, through game design, what it feels like to go scuba diving. Balamut says working on the project has had a pronounced effect on his life, starting with his decision to become a certified diver shortly after joining Giant Squid in 2013.

“During the first month I was like ‘well, I’m making an underwater game, so I’m gonna learn to scuba dive,” Balamut told me recently. In the process, he and Nava went diving near Catalina Island, off the coast of California and not too far from Giant Squid’s Santa Monica headquarters. “It’s especially beautiful because it’s like a conservation area, so it’s just full of life. It’s sort of what inspired the very first area of the game, the green kelp forest area.”

Abzu is very much the game for Giant Squid, which Nava formed after leaving thatgamecompany in 2013. It’s the studio’s inaugural project, and now after three years of development Balamut says he’s thankful to have made the choice to work on a non-violent, exploration-focused game where "make everything feel good" was one of his chief design goals.

“It's much nicer to work on positive, affirming games that are about connecting to nature and...all these more positive themes, than violence or something like that,” says Balamut. He previously worked on a number of projects, most notably PlayStation All-Stars Battle Royale, and seems to view his time on Abzu as a good reminder that the nature of the game you work on can often go to work on you.

“I don't want to work on like, Shooterman 2000 or games like that for three years. That's just blood and death, non-stop. It desensitizes you to that stuff, a little bit,” continues Balamut. “I like playing those games, but I don't think I'd want to work on something like that -- an ultraviolent game -- for years of my life. Like, this game is ten percent of my life so far.”

Of course, every developer is different; lots of folks have no trouble working on ultraviolent games. But spending months or years working on violent, disgusting games does mess with some devs, and Balamut agrees with the notion that the emotional palette you work within when designing a game (think: excitement, fear, fondness, awe) has some effect on the way you see the world while you make that game.

For his part, Balamut says he's spent years trying to design and implement gameplay mechanics that effectively convey the emotions he feels when he's underwater, free to float and explore a gentle (if alien) world.

"The motion of the fish...the diver's motion...it's all very smooth. Which thematically kind of matches up with the ocean. Everything in the ocean is really fluid and smooth and rhythmic," says Balamut. "So we wanted to make sure that like, the camera is always gently moving and not doing a lot of hard cuts or pops. So like, one-frame pops are sort of our enemy."

It's all about flow, and designing a game that players can easily immerse themselves in -- common design goals that are tricky to achieve, even if you're working on a game that's literally about being underwater.

For Balamut, the best way to convey emotions through game design (or at least, the positive, chill ones Abzu is chiefly concerned with) is to design a game that's intuitive and easy for players to immerse themselves in, then keep them in that state.

"I think you just need to try and make sure everything feels good, feels smooth. That way you aren't taken out of the world, and you aren't thinking about 'oh, I need to go do this objective,'" says Balamut. As an example, he points to the way Abzu handles player movement.

"As you're just swimming around, that's designed to be just intrinsically rewarding. Like, we have this button that lets her do different flips. And it's just based on which way you're rotating her, how you're moving the stick. And it has no gameplay purpose. It's purely an aesthetic thing, to let you express the way she's swimming in different ways," he says.

"Boosting is sort of like that too, where she can do different levels of boost that do make you faster, but it's sort of like -- there's a rhythm to it. She does the boost animation, then a bigger one and a bigger one, sort of like Mario's triple jump. And that's just about the feel of like, interacting with the diver."

This isn't new, of course -- researchers have been studying the way humans settle into periods of cognitive flow for decades, and game developers have long tried to apply those findings to designing better games. Abzu is an especially intriguing case, in part because it's so heavily focused on very chill, exploration-focused non-violent gameplay (still a relative rarity in contemporary console games) and because of the very real ways its developers' time underwater has influenced its design.

Balamut says that in addition to being a genuine source of happiness and comfort, his time spent scuba diving had some concrete effects on the design of Abzu. Sure, some of the game's environments are inspired by real-world diving locations (see the Catalina Island comment, above) but on a more fundamental level, Abzu is designed to convey to players what it feels like to exist underwater.

"Feeling the movement of the tides really got to me. That's hard to replicate through game design, unfortunately, because it's a feeling thing. But whenever the diver idles, like, she sways with the tides. And then we actually anchored her so that, gameplay-wise, she stays in the same spot, but she's still moving with it," says Balamut. "And then graphically there's all sorts of things you learn, like the importance of subsurface scattering, like that kind of halo-ing effect around kelp leaves underwater. The light shafts, the way they look underwater, the way color changes underwater, so the reds fall out with distance, and the murkiness of it."

However, Balamut does acknowledge that real water is way murkier than Giant Squid could afford to make Abzu's water, because players need to be able to see what's around them in the game. And what's around them, mostly, is fish -- lots and lots of fish. Perhaps more fish, individually wriggling, writhing and otherwise animating onscreen at once, than any game ever released on the PlayStation 4.

This was what Balamut says was the hardest thing to implement in Abzu. It’s an Unreal Engine 4 game, but getting what Balamut describes as “ten to twenty thousand individually animating fish running on the PS4” without torpedoing performance required Giant Squid to create some “custom tech” that could render giant schools of fish on-screen.

“[The little fish], they're all actually static meshes. They're instanced. There's a single draw call per mesh -- like, per species. And we rely on morph target animation, rather than skeletal, for manipulating their mouth,” says Balamut. “Which means that they can all be rendered at the same time, and with just different parameters for like, this guy's mouth is halfway open. As opposed to a skeletal system, where each....unless you're doing like, instanced skeletal stuff, which is kind of crazy. So that worked out really nice.”

Plus, Giant Squid had to figure out how to realistically replicate the way fish break apart and coalesce to form things like schools and bait balls. The goal, says Balamut, was to create realistic motion: having schools of fish that turn in such a way that each individual fish makes its own semi-unique rotation, rather than having every fish tilt in a direction at once like a flock of computer-generated cylinders with fish skins.

Balamut wound up reading through a lot of scientific research on schooling and flocking, and while he learned a lot from the experience he wound up having to do quite a lot of iteration to get the fish in Abzu moving just right.

"It's an n-squared problem; like, this fish needs to know about all the other fish. And the way I solved that was, I take all the fish and I spatially sort them. Like, this fish is in this part of the world," says Balamut. "And then in memory they're spatially sorted, so where they are in the world determines where they are in memory. And then when I update them, I update them in chunks. So like, these fish know about each other because they're in similar areas of the world, and then also similar areas in memory, which means it's really fast."

Balamut says that took a while to figure out, but wound up being a big boost for Giant Squid because the studio could then put a lot more fish on-screen without bogging down performance.

"It was an enormous speed-up. It made it so we could scale to an order of magnitude more fish," says Balamut. "It's a little bit of a cheat, but it's way faster. I haven't seen that anywhere else, in all my research. I'm not sure if that trick is out there."

Now, with Abzu out the door, Balamut says he's still thinking about fish. Specifically, the way they move and behave underwater, and how games can do a better job of replicating that kind of realistic animal behavior. Balamut and his compatriots at Giant Squid may now be some of the game industry's top experts on the subject, and Balamut says it might never have happened if he hadn't decided to dive headfirst into scuba -- and Abzu.

You May Also Like