Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Vodeo Games founder Asher Vollmer discusses what's under the hood of Beast Breaker, and how he finally figured out what he wanted to do in a post-Threes! world.

Vodeo Games founder Asher Vollmer lit the mobile games world on fire when he released Threes! The game's popularity on iOS and Android gave Vollmer a bit of indie game bona fides in 2014, and the surprise success left him thrilled--but also trying to figure out what to do next.

Recently, Vodeo Games released Beast Breaker, which is like Threes! in that it has its roots in the casual play genre (it's a riff on Brick Breaker), but with a structure and style aimed at fans of Monster Hunter, and stories that feature talking animals but also mature themes.

It's not the first game Vollmer's worked on since Threes! but it's a game that only could have emerged in his journey to find out what kind of games he wanted to make after releasing such a successful title.

Before Beast Breaker's release, Vollmer took some time to chat with Game Developer about the journey to making this game, and how its development was also about exploring better ways to make games.

How do you make a Vodeo game?

After Threes! Vollmer went through a number of other game projects before spinning up the LA-based mobile game company Sirvo Studios, and was interested in making one of his favorite kind of games--the adventure game. That led to the Apple Arcade exclusive Guildlings, a game that Vollmer said ultimately was misaligned with his personal design sensibilities.

"It just was not what my brain wanted to be working on," he quipped. "I didn't want to be managing a content pipeline! I wanted to be playing with toys." He praised the Sirvo Studios team, describing it as Jamie Antonisse's game (Antonisse directed Guildlings), and said his role in shipping it was polishing up the UI and other features before launch.

On that realization, Vollmer handed off Guildlings and Sirvo and went wandering for a bit, thinking about the kinds of games he wanted to make. He came to two realizations--one, there was a kind of game he wanted to work on, and two, he wanted a team working on it in a healthier way.

Vollmer says he'd become enchanted by the magic of the Monster Hunter games, and how monster encounters in those games aren't straight combat--they're "a great solid loop that you can do a lot with." The loop in question being one where players hunt monsters, take their loot, and turn it into weapons with which to fight bigger monsters.

So could that kind of gameplay be done on a simpler scale? Maybe. He became attached to the idea of simplifying the genre to be something like Holedown. But when Vollmer figured out the design, he realized it would take him five years to do it on its own.

And that led to the assembly of the team at Vodeo Games. But with one timeline figured out for Beast Breaker, Vollmer began thinking about the timeline for another game, and another, and so on. How could he be sure that Vodeo Games could be sustainable?

The solution was straightforward--two-year dev cycles, with a goal of annual or semiannual releases. Games at Vodeo are supposed to have a strict prototyping and design cycle, followed by a production cycle. If an idea or gameplay tweak emerges during the latter part of a game's development, it has to be discarded or punted ahead to be used in a future game.

Vollmer's casual invocation of short development timelines might sound surprising to developers who've worked two, three, or four years on even a mid-sized game. "I think games need about two years to get to that really sweet, polished game design point," Vollmer said.

"In one year, you can figure out a good game idea. It takes a year of just ideation, experimentation, iteration, and just calendar time of living with an idea before it's good." He described how many of his game ideas have felt just "fine" for about 10 months, but toward the end of that year something comes together and binds a series of different elements.

The team hasn't quite worked out all the kinks in the production process yet (Vollmer wanted to be transparent, and said the team did crunch on Beast Breaker, pulling some long days), but the hope is that a combination of four-hour workdays and deliberate management choices can improve the sustainability of this rapid process.

One year ideation--one year production. That'll be the path forward for Vodeo Games. Vollmer said it's felt freeing for the team. "It's been incredible for people working on a game to be like 'oh, we screwed that up, it's okay, we'll do better next time.'"

Cultivating chaos

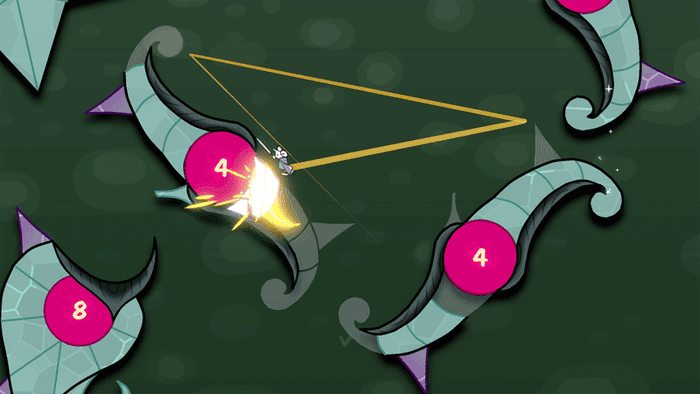

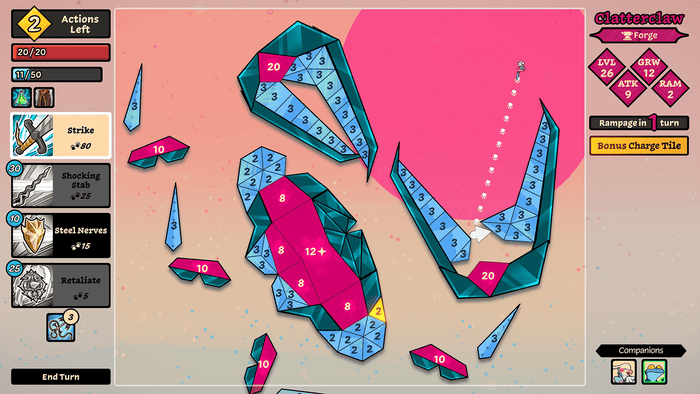

Beast Breaker is a game where your character bounces around like the ball from Brick Breaker, but instead of bricks, you're hitting the armor and cores of monstrous supernatural beasts. Vollmer said honing that design loop was about capturing the visceral feeling of an action brawler game--but it took some turn-based thinking to actually nail the gameplay loop.

"I love turn-based games, I love the strategy in them and the way I can lean back, take my time, and think about making a decision," he said. "When you try to pull mechanics straight from live-action games [like Monster Hunter], things fall apart."

He explained how in real-time games, an easy way to ramp up difficulty is to throw more enemies, and more kinds of enemies at players. So in an early turn-based build of Beast Breaker, Vodeo tried at first to drop a bunch of enemies into the map that would be attacking different areas, with the little mouse player trying to fight them all.

"It was terrible," Vollmer said. "There were so many variables for the player to consider that it weighed them down and turned this small interesting decisions into 'okay, I have to consider every possible move I could make, or I will die.'"

Scaling back from that prototype meant leaning more into the Brick Breaker mechanics. "The simple idea of there being something past those blocks, but you have to break those blocks--it was juicy enough to make players go for it."

That led to the beasts comprising "armor" and "core" pieces. Armor takes damage, but regenerates, while core pieces need to be destroyed to kill the beast.

One other interesting variable for the Vodeo team was the distance that the player character travels while attacking a beast. This is communicated to players when they pick their attack type as "steps." "There was this constant question of, how does the player know where they're going to end up?" Players knew they would stop, but with the large attack zones created by the beasts, it sometimes felt difficult to avoid them.

Giving players information on how far they would travel helped make more interesting choices, and actively let them gain power while also increasing randomness. They can do more damage if they travel further and bounce off more objects, but they have less control over where they land, and may be in an inopportune spot.

A little bit of Eulalia

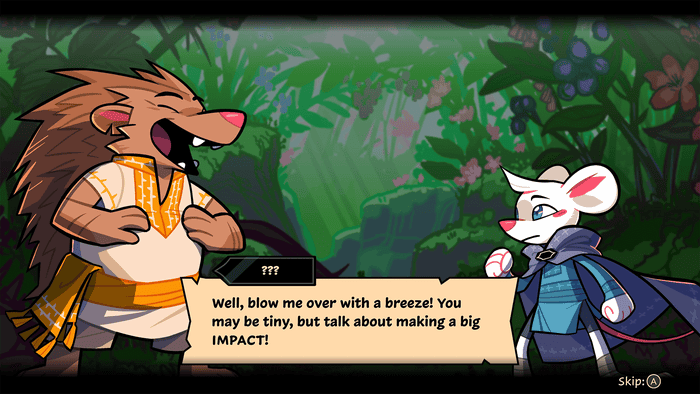

There are a lot of deliberate choice in having Beast Breaker's protagonist be a talking mouse in a world of Redwall-esque talking animals. "The very first thing about the main character being a mouse came from just trying to reinforce the feeling of how big the beasts are," Vollmer said. "I was like 'the beasts are really big. What's a small character we can put next to them? Okay, a mouse--you're a mouse character,' and it blew out from there."

Even though the game's characters and art style aren't deeply enmeshed in the core combat loop (though they anchor a very satisfying weapon-upgrading an exploring experience that helps give players more power), they are tuned to help players feel invested in the beast-hunting experience. Vollmer said there was a clear narrative beat he wanted the team to hit, which was the notion that even with cute animal characters, the monsters of Beast Breaker are "not a natural part of this world."

"I didn't want it to be an elephant hunt," he said. He feels that it's one of Monster Hunter's weaknesses--that players are constantly preying on natural creatures of the world for personal gain. "These creatures are invasive and terrible. They're bad for people, bad for the environment, and bad for everything."

Creating a distinction between the beasts and the world they're invading meant loading the world up with personality, which brought Vodeo Games to the various NPCs you meet. Each one of them--from the protagonist's grandmother, to their hedgehog friend, to a creepy snake character--are meant to embody a different reaction to this ongoing catastrophe.

It's all in service of making sure players don't just feel like big game hunters when they're breaking beasts--they're meant to feel like heroes.

The intent behind Beast Breaker's production and design go hand-in-hand, and it's neat to read the game not just as a distraction, but a thoughtful effort from a team of talented game-makers. If you want to check it out for yourself, it's now available on the Epic Game Store and Nintendo Switch.

You May Also Like