Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Concluding his much-linked article series on the success of Zynga's 70 million user CityVille, following Part 1, design veteran Tadhg Kelly draws further from his What Games Are blog to examine the social features, channels and takeaways from the game's success.

[Concluding his much-linked article series on the success of Zynga's 70 million user CityVille, following Part 1, design veteran Tadhg Kelly draws further from his What Games Are blog to examine the social features, channels and takeaways from the game's success.]

Now let’s move on to the social features. I already touched on publishing as an example of how social features increase visibility, and how they are used for unlocking gates. But they also play a key part in building retention in the game.

There are three kinds of social activity in CityVille: prompts, suggestions and visitations.

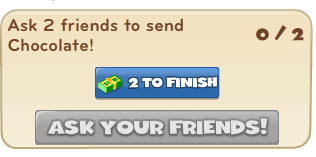

CityVille asks you to invite friends, share your latest accomplishment, or ask your friends to send help so that you can complete a task. In one ten minute session of CityVille that I played yesterday evening, the game prompted me with a question three times, and that is not unusual.

CityVille is constructed to routinely prompt users to take an action. The actions are in the form of a response to a question. Although there may appear to be many variations, there are actually only four types of question that it asks:

Would you like to tell your friends what you have done? (as in the image above)

Would you like to ask your friends for help?

Would you like to send a friend a gift?

Would you like to grant a friend’s request for help?

The game asks these questions mostly in relation to specific events. However because of the way that the game’s activities, timers and open loops work, those events happen very frequently. Here are some examples:

When you attain a level

When you run out of energy

When you build a building that needs employees

When you leave the game open in a browser window for five minutes

When a particular task needs friends to complete

There are also prompts that it asks only at certain points during the game. The following image is from FrontierVille because I missed the chance to screen-grab the one that CityVille asked, but the same function is in CityVille:

This is a cross-promotion prompt. At the start of the game it asks a lot of these sorts of questions, but they tend to trail off into the more routine questions by the time you’ve reached level 5 or so. Other kinds of prompt include gameplay tutorials, guides, reminders and game crashes.

The purpose of a prompt is to get the player to either broadcast to all of their friends, or send a request directly to another friend. There are fairly stringent rules over prompts and how they can be used: They have to clearly ask the player to share or invite friends, for example. The reason is to prevent developer abuses. (See Channels below for more).

Suggestions are buttons, links and tabs in the game that remind the player that they can interact with other players or Facebook friends if they choose. Perhaps the most obvious of these is the friend bar at the bottom of the game:

This bar allows you to travel to your friends’ cities, and also to send them gifts. If you click on any of their images, you will see a Gift button.

Suggestions centre around giving gifts. Most of them are free to the giver (you can give someone energy without it costing any of yours), and they generate publishable stories that the player can share, to let the receiver know that they have received a gift.

The result is an attempt at generating reciprocity. The goal of the gift economy in CityVille is to make players realise that they can actually progress much faster in the game, at no cost, if they give as many gifts to each other as possible. An economy-of-favours emerges, and everyone wins.

One of the most interesting social dynamics in the game is the ability to set up businesses in other players’ cities. It requires their approval of course, but the general idea is that you can apply to set up a franchise of one of your businesses, and this generates pellets for both of you:

Your friend can treat it as a rental opportunity and simply collect coins and experience points from it, like any other building. And you can visit it to do likewise.

Another kind of visit is the performing of game activity in another friend’s city. When you visit, you can harvest or collect on behalf of a friend, and they in turn can choose to accept your help:

This is an example of accepting help. If I choose to say yes, both of these friends’ images will move around my city, harvesting crops and generating resources. Helping friends out in this fashion costs the helper energy, but it also generates coins, XP and, most importantly, reputation points.

Reputation points are like a social form of level (represented by the heart icon on the right of this image). Reputation acts as a secondary requirement on some game activities, just like levelling does, but its primary purpose is to do with XP and coin generation. The more reputation you have, the more XP that someone who hires you will get, and the more you will get also.

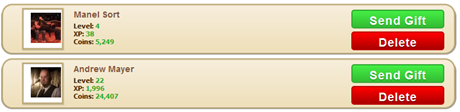

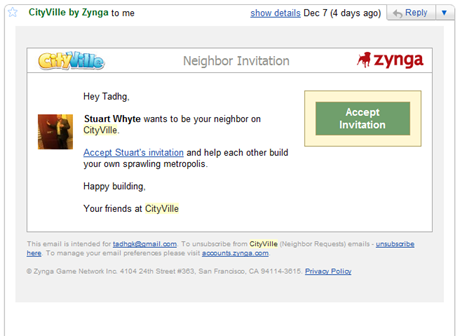

In a similar vein, players can send requests to each other to become neighbors. Neighbors can more easily find and send gifts to each other. Also, some city buildings and tasks require that a player has a specific number of neighbors. Neighbors thus become another kind of gating mechanism.

The objective of all social activity in the game is to generate publishing actions. Publishing, as I’ve already mentioned several times in the article, is the act of getting the player to spread the word about CityVille out onto Facebook. Simple publishing is the act of broadcasting your game high scores onto the platform, but there are more sophisticated channels that can be better used to gather attention.

Specifically, CityVille wants players to generate one of these four kinds of action:

A Wall-publish

A Cross-Wall Publish

A Notification Request

An Email

Wall Publishing: Wall publishing is the most straightforward social action to understand. As I wrote in the first part of this article, wall publishing most commonly takes the form of high scores announcements, or high scores with incentives.

All wall publishing is governed by a specific policy to which a developer must adhere: A game must clearly ask the player whether they want to share a game activity, and then must proceed to a second Facebook screen (see above) that once again asks if the player wants to go ahead and publish this story to their wall. Only then will the story actually be published.

Unsurprisingly, this creates a lot of fall-off. Moreover, a recent change in the policy by Facebook has restricted the visibility of wall publishing such that only players who have already installed the game can see stories published from the game. This change was brought about because Facebook noticed that many of their non-gaming users really disliked these kinds of stories cluttering up their walls, while gaming users disliked stories from games that they were not already playing.

Cross-Wall Publishing: Cross-wall publishing, on other hand, is where the game publishes on a friend’s wall rather than your own. It has the same restrictions as regular wall publishing, but has the advantage that it generates a notification to the player who owns the wall (so they’re more likely to notice it).

CityVille uses cross-wall publishing to tell players when a friend has visited their town. The friend still has to choose to actually publish the story, but as you can see from the screen-grab above, the result is a game story that is more relevant to me than a general achievement publish would be.

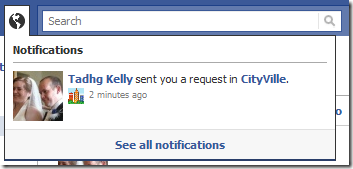

Notification Requests: When Facebook introduced their first major redesign of users’ home pages from a narrow to a wide format, they included a feature called notifications. Notifications tell you if a friend has commented on a status update, posted on your wall, tagged you in a photo, or other similar activities.

Social game developers, including Zynga, abused notifications utterly. If you had ever installed Mafia Wars, for example, you would receive notifications from the game every day asking you to come back and play, offering bonuses, inducements and so on. Notification spam became a huge irritant for users, and so eventually Facebook turned off the channel for developers.

More recently, Facebook appear to have partially relented. While games are still not permitted to advertise directly to players through the notification channel, requests from players to other users are permitted (see above). This includes users who have not installed the game.

Requests have always been a feature of Facebook, but since they started appearing in the notification stream they have become much more visible than before.

Email: Last but not least, email from the game is a valid channel. Email has been available to developers for about a year, but it is often under-used. The hazard with email is that players often consider it to be more personal and private than, say, notifications. So the use of email needs to veer away from spam and more toward relevant communications. CityVille is currently using email as a way to spread requests, not for large scale advertising. This makes it more useful to read (Although on a personal note I think I will soon add a filter to my Gmail to junk those mails).

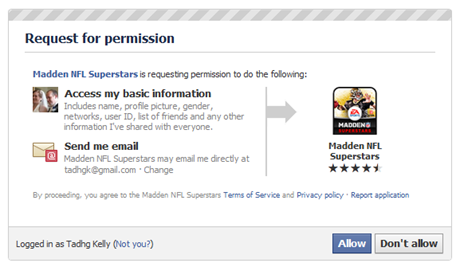

Some of the restrictions around how you can publish, or when, can be overcome by extended permissions. In order to email players, for example, the developer must get their permission to do so first. In order for the developer to access their social graph information, likewise. Other permissions are more added-value types. Players can give you permission to automate the process of wall-publishing, for example, to reduce it to just one step rather than two.

There are several ways to ask for permission. Some games try to make a mini-game out of it by inviting players to complete several steps in a social bar at the top of the game to get a prize, like this (taken from Pet Society):

Others, like CityVille, bundle their permission question in as a part of the install question when the player first enters the application:

And some do both.

The mandatory method is more effective of course, although there is the possibility that if you ask too much of the player at installation then they might get put off.

To understand the social dynamics of CityVille, realise that they are selfish.

In each case, the dynamics exist to tantalise a player with a tangible reward. If you visit your friend, you get a prize. If you send them a free gift that costs you nothing, they might send you one back. If you set up a bakery in their town, you will both gain from that. If you harvest their crops for them, you will gain reputation points.

It’s all incentive-driven. One of the ironies around social games is that they aren’t particularly social. They don’t encourage deep social interaction because such interaction is useless to the developer. Social games are not trying to be connections or meaningful experiences for players. That is a wholly different kind of game, and not one that they can easily become given the environment in which these games are played.

Instead, they are built as amusements. Socialising in amusements is more akin to having spare Poker chips at the table that you give to someone else, and maybe they’ll give you some back later. It is reciprocal trade, assistance for incentive, not charity. While this does not preclude the possibility that some players will engage in acts of charity for personal reasons, the social dynamics are not created with that in mind.

They are built to work with self-interest.

For the final part of this article, there are two things that I want to cover:

Money: How does the financial model work?

Comments: What works in CityVille? What doesn’t?

Nobody knows exactly how much profit Zynga makes from their games. There is only guesswork, analysis of second hand information, anecdotal stories, correlations from other companies and data points around the web. The general consensus seems to be that the answer is: A Lot.

The most common executive-summary pieces of knowledge or social games go something like this:

The average game makes $0.25 per MAU per month in revenue

Another way of saying that is that the average game makes $0.03 per DAU per day

Somewhere between 1% and 3% of users pay in any given month

Somewhere around 20% of users of a game will pay once over the course of their lifetime of play

A small (0.1% or less) percentage of users will become heavy users (the unfortunately named whales)

Whales will spend a lot (> $100)

Players will spend as much on intangibles (gifts, objects of status, virtual Christmas trees) as on tangibles (gameplay benefits).

ARPU is low (lots of players never pay at all) but sustainable over the long term, unlike retail

Obviously this is all hazy. But it tells a story, and that story is that games-as-a-service is both a real opportunity, and one that is reliant on both visibility and retention (as already discussed in the first two parts of this article). The longer and louder a game booms, the more paying customers you will find. And the more whales you will find also.

This means that a social game needs something to sell. In CityVille’s case, that something is game cash.

CityVille, like many online games, has two virtual currencies. There are actually five different number quantities that the player earns (reputation, goods, experience points, coins and cash) but only the last two are currencies. Reputation and experience go toward accumulating social and game levels, while goods are for resupplying existing buildings. Game coins and game cash, on the other hand, are used to buy stuff.

So why have two currencies and not one? The simple answer is that a dual system allows Zynga to separate high revenue actions from low revenue actions more easily, so that one can spiral with inflation while leaving the other untouched.

In many early massive multiplayer games, inflation was a noticeable problem for game economies. What tended to happen in games with only one currency is that they either served the early part of the game, or the late part, but not both.

Suppose a game allowed a player to buy magic swords for 100 gold pieces. To an early-stage player that could either be really expensive or relatively good value, depending on how difficult or easy it was to earn 100 gold pieces. The problem is that the late-stage player already has been using those gold earning opportunities for weeks or months, which means that if 100 gold pieces is hard to earn then he is satisfied. If it’s easy to earn, however, he is falling down in gold.

So what?

So if gold is hard to earn, this creates a disincentive for new players to join, because it will take a long time for them to get anywhere. Conversely, if gold is easy to earn, then the early-stage player is happy, but the late-stage player has nothing to really aim for. So they will hit their maximum mastery quickly and then leave through boredom.

The solution, adopted by many games, is to have two currencies.

CityVille sets it thus: You have an easily-earned currency (coins) that you collect from most actions, and hard-to-earn currency (cash) for high value transactions.

You get coins for harvesting crops, collecting taxes from buildings, trading with your train, and some bonus actions. Coins are plentiful, and you use them to buy buildings, plant new crops and other day-to-day activities. They are perfect as a resource for the early-stage player to worry about, but by the time you reach level 10 or so the typical player will not worry about so much about coins any more.

Cash, on the other hand, is almost impossible to find. The game only awards you one point of cash every time you gain enough experience points to earn a level. This means that the denominations of cash are very small (you spend it in ones and twos) and you spend it quite carefully.

Many of the transactions associated with cash involve using it as a way to shortcut key tasks. In the example image above, I need to either ask two of my friends to send chocolate, or spend two of my hard-earned cash, to complete a mission. To ask for that chocolate, however, involves a publishing action on my Facebook wall.

What cash is essentially offering is trade-offs. Cash is an option that you can use to avoid social embarrassment or to skip forward in time. It is not generally used to purchase objects (although there are a few exceptions). Cash buys you progress, not stuff.

The other thing about cash is that the manner in which you earn it obscure. Because the cash only increases when you gain a level, it is easy to miss. It appears, on the surface at least, that the only real way to accumulate cash is to get out your credit card.

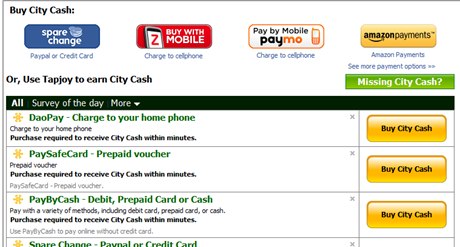

There are three general routes to payment. The first is this button:

Simple to understand, the Add Coins & Cash button takes the player to this dialog:

Notice that Zynga are actually offering both coins and cash for sale. Cash is clearly the more prominent of the two, but it’s interesting given how easy it is to accumulate coins in the game. Perhaps it works, there’s no information to tell.

Also notice that the pricing is based on packs of cash, not an exchange. It is also US-style, where they add taxes on at the point of sale rather than including it in the price, as the EU does with VAT. Subbing 12% off the value of each (which is what the tax appears to be), what Zynga are actually charging for cash is:

15 cash for $2

40 cash for $5

75 cash for $9

170 cash for $19

465 cash for $49

1000 cash for $99

The top transaction values cash at $0.13 a piece. The bottom transaction values it at just under $0.10 however, with the rest forming a sliding scale clearly showing that more dollars spent is more advantageous.

In all likelihood, very few players actually buy that $99 pack. Pricing psychology often works in such a way that a very highly priced item helps to set the tone for the value of all other items (in consumers’ minds), leading them to choose the mid-range item. It is likely that the $2 pack is not the most popular for the same reason. It seems poor value, even though in reality it’s only marginally less so. Most players will likely transact at the $9 price, because that seems to be a good range.

The surprising thing about the pricing here is that there is no $999 pack offering 12,500 cash. It would probably get only a microscopic number of transactions, but it might move more average customers from $9 to $19.

An offer is an available discount, membership or survey that the player can fill in, in exchange for which they receive some cash.

Offers were very popular among social game developers eighteen months ago, but they started to attracted heavy criticism for resurrecting the bad old days of lead-generation marketing (which had been tried and proved not to work well because it attracts poor quality leads).

What really caused a storm for offers was, however, ScamVille. Techcrunch ran a series of impassioned articles investigating exactly what was going on with FarmVille’s offer walls, and discovered that it was a hotbed of mobile phone scams, spam email sites and all the other sleaze that sits on the underbelly of the Internet.

This led to offer walls being pulled from a raft of games, and then returned slowly in a more controlled and managed fashion.

It also led (anecdotally) to a drop in their effectiveness. At the same time, Facebook began to push hard to get their major developers including Zynga to adopt Facebook Credits as their primary source of payment.

Although credits took a larger percentage for processing transactions than other vendors’ solutions did (30% as opposed to 10%), Facebook’s argument was that they would be more trusted, and so yield more transactions. (Again, anecdotally, this seems to be true). Facebook Credits do not include an offers wall.

CityVille still uses offer walls, but currently only as alternative payment providers:

The offer wall is located behind the Earn City Cash tab. And here’s what it displays:

The offer wall is provided by a third party company named Tapjoy (formerly Offerpal). Currently, it only contains alternative payment methods that the Facebook Credits system doesn’t cover well, but the typical use of such systems is to run surveys, offers and Netflix subscriptions. (It is also possible that those options are displayed in other geographical territories than the UK.)

Quite whether this system is really that effective for CityVille is debatable. It feels very much like a legacy system these days compares to the clean ease of use that Facebook Credits brings, and will probably end up being deprecated at some point in the medium future.

Finally, there are payment cards. In many supermarkets across Britain and the US (and beyond), there are cards for sale that you can redeem for credit in social games on Facebook. These cards are targeted at consumers who might not have credit cards, similar to credit-based mobile phones.

They work pretty simply. You buy the card, redeem it in CityVille or one of Zynga’s other games, and you receive cash to that value.

Payment cards are a relatively recent innovation, first introduced by Playdom, and adopted by some of the other major developers this year. They are highly accessible, and their continued widespread availability would suggest that they are working.

To be fair though, payment cards are very much a late-stage innovation for companies that have already achieved considerable scale. They require production and shipping and more traditional bricks-and-mortar retail concerns like that, which is generally pretty expensive.

I’ve been through CityVille with a toothcomb and examined how the application is structured. I’ve talked about the importance of visibility, retention, open loops, social aspects, reciprocal trade and – now – the payoffs.

Will it stay popular? Undoubtedly so. But for all that success, however, there are some comments to be made on it, in terms of things that it could be doing better:

Energy: The energy mechanism is archaic. In the old days of social games, energy was really the only system that prevented players from burning through a game very quickly, but with CityVille already deploying many timers, it seems overly punishing on players to have them watch their crops die in the fields just for a lack of energy. The thinking here is clearly to get players to buy more energy, but that creates nothing but negative feelings. My suggestion here would be to either abandon energy altogether, or to significantly relax it in some fashion.

Cruft: The game does not need so many payment options. The Tapjoy inclusion in particular smacks very much of an unwillingness to clean house. While there are always metric arguments to be made for that extra percentage or two of revenue that may result from such things in the shorter or medium term, design cruft tends to obscure larger issues. The hazard of a metrics-only focus is that it tends to devalue cruft concerns, leading to a company’s products becoming formulaic and stale. MySpace was cool until it became overrun with cruft, and Yahoo likewise, and it’s hard to decide to be elegant in design because there is often be no immediate reward for doing so.

Automation: Harvesting and collection behaviours work very well in a game like FarmVille where they are natural, but the lack of automation for manual labour in larger play areas (such as a city will become) is a net negative. CityVille will need to include some degree of automation of collection and harvesting features eventually if the game is to scale its experience. Perhaps these options already exist at later levels, but if they do I have not seen them yet.

$999: The game should have a massively priced pack of cash. Just to see what happens.

Cash: It would be nicer if the game was not tying cash transactions to social embarrassment. In particular, creating tasks that are obliging either wall publishing or paying cash cannot instil anything other than a negative feeling toward the game. Time-skipping or individual requests/invites are ok, but forcing players to either out themselves in public or pay up is not the sort of thing that sits well with the charm and thauma that the game is aiming for.

Next Game: I think Zynga needs to strike out with its next game. Farms, poker, mafias, restaurants, cities and fish are all well and good, but they are also pretty run of the mill now. Zynga’s history has long been to wait for other companies to find trends and then to make their own versions, but the period of time that it is taking them to developing those versions is growing. FarmVille arrived into the market mere weeks after FarmTown, but that’s not a pattern on which Zynga can rely indefinitely. They are already late to the city-sim genre, and it’s only their existing scale that’s making that work for them. I wouldn’t want to base a 5-year strategy for the company on that sort of tactic because it is inherently unstable.

CityVille is a genuinely interesting case of what happens when a social game developer that has all massive resources at its command puts its mind to the task of making a big game. It’s Zynga’s major effort for the latter half of this year, and it has to be said that the execution in all areas is mostly excellent. The game is charming, engaging, socially connected, technically extraordinary on the back end, and just very very impressive.

No doubt many developers are casting envious eyes upon it and asking how could they get in on some of that action, and will be spinning up their plans to make a city simulation as we speak. This is a massive mistake, but they’re going to do it anyway.

I was motivated to write it this article by what I consider to be was a lot of ignorance on the part of would-be developers as to what the levers of power in social gaming really are. Clearly there are many, from Metcalfe’s law effects on visibility, to open loop game design. Some of these you can easily clone, but let’s be honest: Unless you have $50m for advertising and five games to cross promote, you’re not going to really be able to play in the same pen as Zynga.

Zynga are in a position similar to Facebook and Google, where they have become such a dominant incumbent with so many invested users that they have created a buffer around themselves. Hearing a social game company talk about how they are going to spend $300k on development, making their own cheap knock-off games, and then become The Next Zynga is like listening to small startups convincing themselves that they just need to make a better search engine to take down Google.

These people are fooling themselves, and usually doing so with no-brainers. Instead, the secrets to success are:

Be Radical: Radically innovate a new kind of game. This is always an opportunity for those brave enough to try. Treasure Madness, Farm Town, Restaurant City, Bejewelled Blitz, Happy Aquarium and many others were all major innovations in their time, and even though Zynga has copied most of them, the original games didn’t just die off. If you make something radical, it can work really well and it may become a stepping stone to something bigger.

Get Bought: The next option is to build a great game and, if Zynga or someone else comes a-calling, join them. The original developers of YoVille and Warstorm were both acquired by Zynga, and their founders and investors have presumably done quite well out of it. Zynga, being huge and independent as they are, can afford to make acquisitions like this just to see what might happen.

Stay Small: While the Zynga strategy rewards the mainstream amusement-level engagement handsomely, it has no interest in niche ideas that are thought to only have a loyal but small audience. Facebook may not be the best venue in which to try such ideas, but deep engagement with games is possible if you approach it right. Vikings of Thule has been plugging away with a little card game for a couple of years and has a raft of loyal users who come back to play it regularly. It will never be a huge hit, but it’s perfect for a tiny team that just wants to make a game.

Be The Platform: You don’t have to be on Facebook. BigPoint aren’t, and it’s worked out very well for them. By not being on Facebook, but instead using Facebook Connect or similar features, you are likely to not get quite the hoard of users that a Zynga game can generate so quickly. On the other hand, you have much more ownership over the customer and they are in a less distractible state than when inside the Facebook interface. Both of these can be very strong advantages. They certainly have been for Moshi Monsters.

This brings an end to the article. I hope you have found it very engaging. The topics covered in this article touch on some of the foundations of what’s going into the What Games Are book. The book aims to discuss the subject of games in a grounded but broad way, encompassing not just social games, but casual, so-called hardcore, the motivations of game playing and the art of game creation.

It’s a fascinating subject to many of us, and I hope that you’ll choose to subscribe to my blog to hear more and discuss. Thanks for reading.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like