Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A few years ago, I set a goal for myself: Make 100 games in 5 years. This post is an update at the 2.5 year mark.

For the past two and a half years, I’ve been working through a challenge, a goal that will carry on until June 1st, 2017: making and releasing 100 games in 5 years. This piece covers a bit on how the challenge came to be, how I’m doing now at the halfway mark, and what I’ve learned from this method of game development.

I’ve read several year-in-reviews, and (although I’ve never done one myself) the idea of penning one was intriguing. It seemed like a great way to organize the past twelve months into a single meaningful document. Sort of like a postmortem of a year: peering back on development and growth, laying out what went right and wrong, how it could be improved upon. But quickly I realized that this past year’s games couldn’t easily be untangled from an overarching goal set in June; a June roughly two and a half years ago.

“11 games in a year? That’s almost a game a month,” friends would tell me.

“They’re mostly short freeware games” I’d think to myself. I can’t recall if I ever answered back with that.

But if I did ever say it, I’m sure they’d have responded with something akin to “James, drop the adjectives. You’re pretty much making a game a month.”

Either way, my development speed didn’t feel fast. It felt like I was sluggishly crafting these interactive things, inept hands in Geppetto’s workshop. My first self-made game was Landers, a short critical game that put the player in the shoes of an invader from Space Invaders. The second was a game about not killing a cow. Then a few others, including the cat licking game.These games didn’t really have any uniting theme or art style or subject matter; they were kind of all over the place.

Heading into 2013, I wanted to find my voice. I kept working on new projects: one, two, three more releases. Besides my tendency to use pixelated graphics (I promise that I’m trying to cut back), the themes were still all over the place. This one is a critical game about first impressions; that one is a silly game about a screaming teapot. There were few shared ingredients within the batch.

I wanted to uncover my voice, so the goal was set: 100 games in 5 years. Of course, this idea didn’t come from thin air, nor did I spontaneously decide to make critical games. While at Miami University of Ohio, I was taught rapid prototyping by Lindsay Grace, who introduced me to the Experimental Gameplay Project and inspired me to create critical games. Through his Critical Gameplay Lab, specifically games like Wait, Levity, and Black/White, I grew fond of questioning accepted game conventions and the idea of making games with a deeper meaning. His mentorship was invaluable.

For a bit more context, at the time the challenge was set, I was buying into Gladwell’s 10,000 hours to succeed theory. While 100 games in 5 years doesn’t equate to 10,000 hours of work, and regardless of how real Gladwell’s theory is, this felt like a good, reachable, yet challenging, goal. A way to keep on my feet and move forward. Mastering rapid game-making wasn’t the aim, I wanted to discover my artistic continuity within the medium.

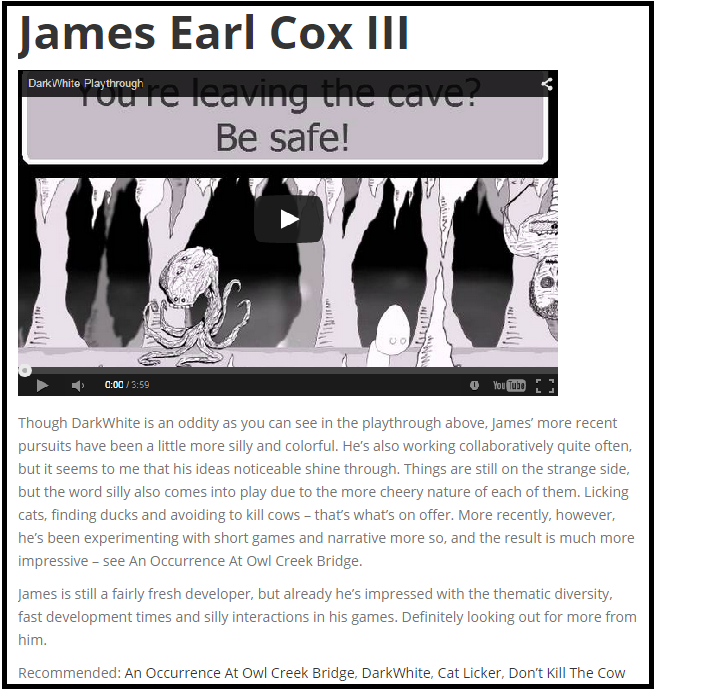

As I continued producing freeware games, indie news outlets began to pick them up. IndieStatik covered a few of them. There was a piece on my intermedia adaptation game An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, and I’m pretty sure Potato or Big Minta Bronson: A Vegetable Love Story made it into a Ludum Dare round-up. Then in April of 2013, this article came out: Who Is the Next Cactus? It covered several freeware developers: Jake Clover, Zak Ayles, and Jack King-Spooner to name three. An excerpt can be seen below.

I felt out of place next to the amazing developers on the article’s list. They had unique art, strange, fascinating worlds to explore, a plethora of artistic vision that I felt lacking in. There was one element where I excelled, though: making games and doing it fast. Then it struck me, I was overlooking quick development as a skill, one I’ve been developing over the course of this challenge.

Since then, the tone of 100 games in 5 years has changed. Rather than trying to find a voice through rapid development, the goal has become almost the opposite: Explore the edges of games, continue creating interactive experiences, and hone rapid development as a skill. Collaborating is welcome and encouraged.

The table below summarizes my progress in this challenge:

Year | Games | Press | Conference Selections |

|---|---|---|---|

———- | ——————- | ——————- | ——————————— |

2012: | 11 | ~12 | 2 |

2013: | 17 | ~29 | 5 |

2014: | 34 | ~43 | 11 |

Total: | 62 | ~84 | 18 |

(The number of games made each year; how many articles mentioned them within that year; and conference selections, based on how many games were displayed at conferences, festivals, and expos)

Significant events associated with games created during the 100 games challenge:

Don’t Kill the Cow is a runner up for People’s Choice at Meaningful Play Conference.

Don’t Kill the Cow is awarded People’s Choice at GLS 9.0

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge is awarded Silver at Serious Play Conference

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge is awarded Most Meaningful Game at Meaningful Play Conference

An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge is displayed at the Smithsonian Pop-Up arcade

World the Children Made is awarded Silver at Serious Play Conference

World the Children Made is awarded Game of the Year by AIMS Games Center

World the Children Made is awarded Best Digital Game 2014 by AIMS Games Center

Kill the Kraken (big field game) is awarded Best Spectacle at Come Out & Play

Kill the Kraken is a special select for IndieCade

2001: A Space Masquerade (big social game made with Brian Pickens) is displayed at Come Out & Play, San Francisco

EnviroGolf is displayed at EGX in London as part of the Leftfield Collection

(write-ups and conference listings can be found on each game’s page at SeeminglyPointless. Most of the digital games can be found and played on my Game Jolt page)

A few things to point out; I listed Kill the Kraken and 2001: A Space Masquerade as being displayed at Come Out & Play and Indiecade, noting these two games are not digital. While most of the games I’ve created so far are digital, six are analog. Also, for the press section, these numbers may differ slightly as websites come and go.

Ten of the games I made are hidden around the internet, experiments waiting to be discovered or utilized in other activities. I don’t list the names of these games here or on my site, but they are still included in the count (as well as the six non-digital games). Ideally, I’d like to surpass the goal with enough freeware digital games to make it over “100 freeware games in 5 years.”

2014 was the most successful year so far. My game output more than doubled that of 2012 and provided encouragement that this challenge can be met. Out of all the games, my favorite children are An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge, Don’t Kill the Cow, Temporality, and Bottle Rockets. Interestingly, these games are all on the more serious/art game end of the spectrum.

Also, I didn’t get this far alone. A strong development community is vital. They can playtest, collaborate, inspire ideas, and provide feedback. It’s almost like a writers’ colony, except online and with games. For freeware games, Game Joltprovides an inspiring and supportive development community. A recent post of mine describes some valuable experiences with Game Jolt’s developer community (here). Even outside of Game Jolt, there are too many people to name who helped me reach this point. During these 2.5 years, I certainly learned that a strong support system is essential.

In line with the Experimental Gameplay Project’s findings, the caliber of the design seems to have no correlation to length of brainstorming sessions or how much time I spent working on an idea. On a similar note, I often find it hard to know if a game will be liked or not. My brother and I made EnviroGolf, a game based on a silly joke between us, in a week and it was written up on Kotaku. In contrast, my partner at the time and I spent two months working on Runner and it remains relatively untouched.

I’m happy to say that, even with increasing numbers every year, the quality of these games has not gone down. There is sure to be a creation cutoff point, and I wouldn’t be surprised if I hit the development wall in 2014, but even so, 34 quality freeware games in a year ain’t shabby, and at this rate I’ll be sure to reach the 100 game goal on time.

While the 100-in-5 rapid turnaround time may not be as intense as Adriel Wallick’s One Game a Week, the Experimental Gameplay Project, or the 90 Day Dev Challenge, there are several advantages to the path I’ve chosen, as well as some downsides.

Games never die (mostly). Plausibly the reason for the article count increase every year is because these games are still fresh and being found; none of them are more than 2.5 years old. Similar to how I revisit Terry Cavanagh’s Naya’s Quest and Don’t Look Back, people frequent these 100-in-5 games over time. Some games take off as soon as they are released; others go unnoticed for months before being played. Murder Clown was relatively quiet until Markiplier played it. Having a growing number of games out there increases the likelihood of exposure.

This challenge hones scoping and rapid development. While game jams can teach you how to cut features and settle on realistic goals; it’s hard to get a feel for scoping without making and releasing games. Not just one game, or a jam game, but multiple complete games. At this point, I can usually tell within a day or two how long a project will take for me to make.

Because the challenge is 100 games in 5 years, development times can be adjusted as needed until a game is good to go public. One of my key rules is that I will not release a game until it feels complete. While some of these games only took a week or two to make, others were worked on across several months. Development times can vary depending on collaboration partners’ schedules as well. This differs from the One Game a Week Challenge and 90 Day Dev Challenge as the 100-in-5 allows each individual game to be a recognizably standalone artifact; yet this is also part of the first disadvantage of making 100 games in 5 years.

Because each game is a standalone artifact, because I don’t have a defining style, and because I often work with others, these games often aren’t linked to each other, nor to me. People might remember that silly-game-about-racing-fish-people-set-to-a-Kanye-remix, but they probably won’t remember who made it, much less that the same person made a serious game based on a Civil War short story. Unless the developer has a name for themselves, works mostly solo, or has a recognizable style, the player may not recognize that these artifacts are connected.

Another downside is that, because these games are not being developed further, the excitement generated from press often fades radpidly. Rather than build to a release, or grow an audience for a title, these freeware games typically exist solely as present experiences.

Possibly

the most obvious disadvantage is that this is a 5 year commitment. If you can’t pace yourself, it will end badly. And it might not fit well with other long-term commitments. This challenge worked out well for me because it will conclude as I graduate from USC’s Interactive Media and Game Design MFA program. I didn’t plan it that way, but I’m happy it’s turning out as such.

Lastly, as of now, I can’t say I would recommend this challenge to anyone. Since it hasn’t finished yet, we don’t know what the long term outcomes will be. More so, it feels like an experiment with long term rapid development, rather than an example to set. It can be exhausting at times, and the tunnel is long. But none of this is bad; it’s a learning experience, and I wouldn’t be doing it if I didn’t love it.

And so we head into 2015. If I’ve learned anything from these past 62 games, it’s that you never know what to expect. However foggy the future is, there will be more games—lots of them.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like