Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The article addresses creating an in-game balance and will be interesting to anyone who takes part in the creation of games, especially producers and game designers.

The making of a good game involves the collaboration of a few teams: artists that create look & feel, game designers that come up with mechanics and narrative, programmers & QA that provide bug-free code. Balancing the game is key for the whole thing to work—and ideally, it should be done by a Game Economy Designer, who balances all numerical indicators in the game, ties them to each other, and, if necessary, works on monetization.

In spite of the fact that in small companies creation of the game economy often becomes a responsibility of a game designer, economic expertise is extremely important for balancing: it allows to see the big picture, draw parallels with real life utilizing various scientific methodologies.

In 2010s the largest publishers began to hire economists as game economy designers, and Room 8 Studio followed this trend by establishing a game economy team, led by a professional economist with experience in applying scientific methods in a variety of game genres.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

So, what are the basic steps in creating a balanced in-game economy?

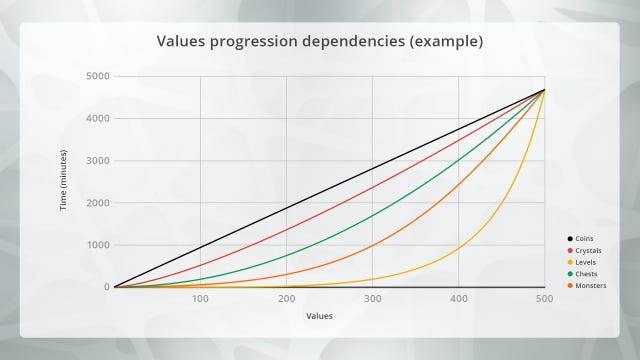

From the classical theory of value, and simply from common sense, we know that time is the main resource for anyone: there’s never enough of it. Therefore, we will compare all game values to time, placing the latter on the X-axis in our coordinate system. The main value of a game is something that motivates players to spend time in the game. There are 4 player types by their most valued in-game actions:

Explorers, who enjoy discovering areas, going through narrative and learning about hidden places;

Achievers, who prefer to gain "points", levels, equipment and other concrete measurements of succeeding in a game;

Socialisers, who enjoy game's communicative facilities, and apply the role-playing that these engender;

Killers, who thrive on competition with other players, and prefer fighting them over bots.

Best games offer a combination of these values so that each player is engaged. In this step, express each of these values in terms of time so that if, for example, a person wants to climb to the top of the leaderboard, they must play the game for a month and go through the entire content. Or if they want to shoot all the monsters, then again—they must play for this same month. And so on. We need to calculate these indicators as if for the abstract ideal player, who makes their every move perfectly. Thus we translate values into functions where the ordinate of the coordinate system is time, and we can have anything at the base, ranging from levels a player passes to the number of dead monsters. Then, knowing how many levels an average player passes in one session and how many they pass per day, we can say, for example, for how many weeks 300 levels will generally last.

To keep the player interested, the function of the game’s complexity must be a curve that grows either exponentially or linearly. In any case, an increase in complexity will take place quickly.

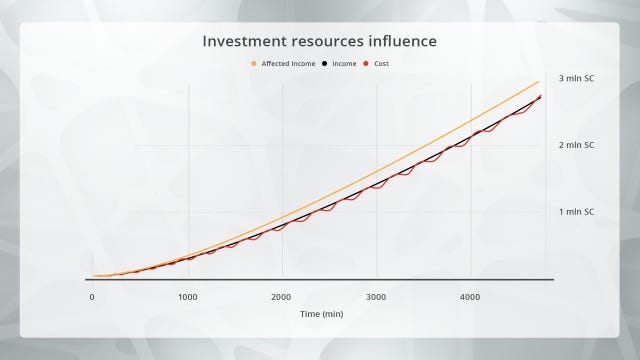

Investment resources are those that influence the speed at which the player receives the main value of the game. Such resources should be expressed in terms of time, and then limited in order to maintain balance. It is very important not to have investment resources, that can bring long-time profits, depend on chance or random factors.

There are certain resources that may slightly affect the development of the character—for example, one-time boosters, that help players finish a level a little faster. Although the effect of such boosters is largely insignificant, they should be taken into account and evaluated in relation to time. Non-investment resources do not affect the player’s development. For example, skins that just visually delight players. However, they should be taken into account as well, since players spend money on them, similar to the luxury goods that people buy in real life economy. Sometimes even a character’s experience can be a resource. One can’t spend it, nor buy anything for it, but it may be vital for the game’s progress. For instance, until the player gets a certain amount of experience they cannot get some kind of upgrade. Thus, these experience points become the resource that may be in deficit. Usually, resources of all types are described by the game designer at GDD creation, but the game economy designer still needs to carefully check all the mechanics to spot any additional resources that were not taken into account.

When making progress, players earn in-game currency, called soft currency, or certain content types which they pay for. Using the dependencies we’ve defined in step one, we can now match game values to each other and to the soft currency. Then, build dependency graphs that show that, say, in order for a player to get through all the content, they will need one month or 1 million soft currency. This method allows you to put correct prices and determine how much everything is worth. For example, a player gets 60 coins for passing a level. How often will they get these 60 coins? At what point in time will they collect, for example, the 3,000 coins needed for an upgrade? What will they spend and at what points? Having such a schedule, the game economy designer adjusts the player's income and expenses for all the in-game resources.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

At this stage, we usually do not operate with absolute numbers, but rather with variables and dependencies.

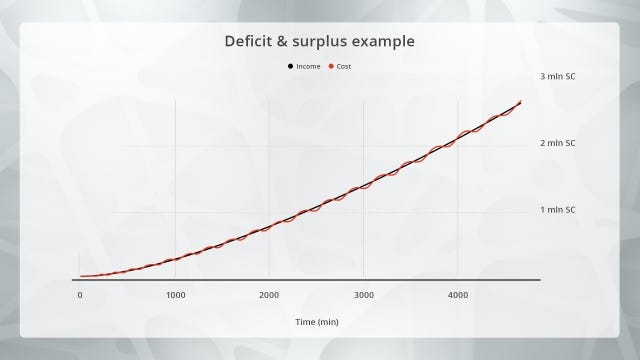

To engage players, let them experience the whole range of emotions. The player won’t feel the buzz of victory if he or she haven’t tasted the bitterness of defeat, because the juice of the game comes from the balance between difficult & easy, interesting & boring. Accurate adjustment of this balance allows players’ vivid emotions, for example, of the very last move win. Expenses curve may vary in a sine wave, as well as income, or one of them can be linear. In this case, the player will experience a deficit in some periods, a surplus in others. Such a situation is absolutely similar to the real-life economy and economic cycles. In the period of the overheated economy, the people have a surplus, and feel the deficit of the currency in the periods of economic crisis. I also like to implement real-life economy trends in the in-game balance. The reaching of maximum profit earnings by the player is similar to the overheated economy, where the shop increases prices like the households increase the desired salary on a real labor force market, also the number of goods offered in the shop is set to the minimum because the overheated economy doesn’t have such a thing as unemployment. Creating such flow, we influence the player's feelings, because sometimes he has to strain himself, and then gets rewarded.

The best practice is to offer 2-3 emotions per game session. There are difficult levels, though, when a player feels the only rage during the whole session: rage forces one to pay to get through obstacles, and such tricks can be used for monetization.

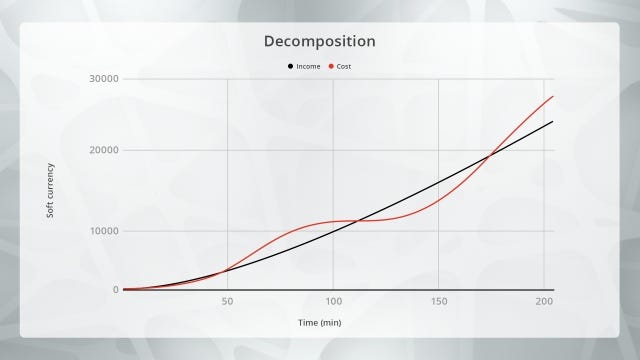

Now that there are dependency plots for a period of time ahead, you need to break them up into segments and balance them inside these segments, getting the zero-sum game as the output. This means that if you count all the total revenues and all expenses, they will add up to 0 and this is an example of a perfectly balanced economy. In free-to-play games, sometimes the expenses are designed to be greater than the income: it forces the player to pay. To avoid pay-to-win pressure, use ‘walls of patience’ — when a player can pass a level, but they have to make an effort or spend significant time to do it. Alternatively, they can donate or watch an ad, thus obtaining the opportunity to pass the level quickly. Start decomposition by setting correct timeframes for future balancing:

The first-time user experience, which must be calculated for every second

The first day, calculated for each hour

The first week, calculated for each day

After that, balance things out for every week. If there are any special requirements for the game in terms of the deficit, then slightly increase spendings.

Having worked through all these 5 steps, at the output you will get a balanced and manageable economy with defined dependencies.

Balancing the game economy can seem like a daunting task to even for the most experienced game designers. However, there are rules, guidelines, and models you can adhere to that can help you get the best out of your game and truly get started. If you don’t have the skillset on your team to model the game economy, the task can be easily outsourced. The guidelines we’ve covered are a great base for building a balanced game economy. But every game is unique and needs a custom approach, which involves continuous monitoring of players’ behavior, adding new levels, content, sales events, boosts, new mechanics, etc. All these influence your game economy where any change requires a clear understanding of how it affects players’ behavior, retention and, ultimately, revenues. We’d be happy to help with:

Game economy design & consulting

Analysis and decomposition of your gameplay & balance

Level design

Have a project in mind? Contact us to discuss how we can leverage our experience to help you create the next best game.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like