Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This round-up from various conference talks, blogs, and streaming discussions is a treasure trove of insight into what made Breath of the Wild great.

.webp?width=1280&auto=webp&quality=95&format=jpg&disable=upscale)

Nintendo is not what you’d call an open, chatty company; its internal development is a process we’re rarely given a look at, making the fine details of its success sometimes a mystery. With Breath of the Wild, we may not have a universe of readily available insight as we might with other games, but over the years, Nintendo’s team has opened up on a few occasions to give us a peek behind the curtain, with a few tantalizing bits floating to the top.

With the sequel on the horizon, we thought it was a good time to revisit some of those lessons, as well as add in a few of our own observations. Here’s what we’ve learned.

Breath of the Wild was intentionally built as a convention-breaker, as technical director Takuhiro Dohta explained in the first part of the GDC 2017 talk, Breaking Conventions with Breath of the Wild. The design goal was to turn the game from a passive experience, where players were led through a linear story, to a more active one that encouraged player engagement by eschewing the progression gating that historically has accompanied its open-world design. This meant removing the unscalable walls from previous titles and letting players climb over any surface, and also buffering the consequences of their more impulsive behaviors by giving them a cushion (the paraglider) to mitigate fall damage.

The resulting feature, along with other, more traditional means of travel, rewarded player curiosity by allowing them to take the scenery however fast or slow they liked. Walking, riding horses, paragliding and even shield-surfing: if players were in a hurry to get to a tempting new spot or simply taking in the sights, they had a way to take each location at the pace they preferred. For a game as big as Breath of the Wild, this was key.

It’s not uncommon for games to feature special navigation tools to help the player find their way, including forms of “detective vision” that let the player see around or through obstacles as a timesaving measure. But carefully designing the player’s horizon can eliminate the need for many of those tools. In a talk at CEDEC 2017 entitled Field Level Design in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (later translated by Matt Walker), director Hidemaro Fujibayashi and senior lead artist Makoto Yonezu delved into this topic further, highlighting how the topography of Breath of the Wild played an immensely strategic role in the players’ progression.

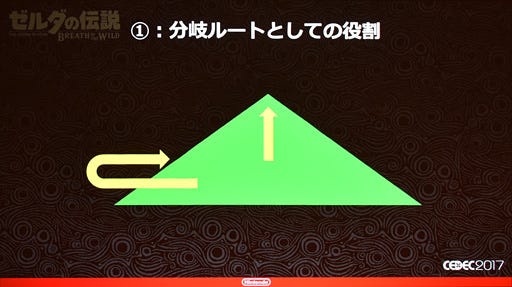

A slide from the CEDEC 2017 talk illustrates part of the triangle approach, depicting a mountain and the choices the player has in direction.

The idea is to use the shape of a triangle to inform how structures are situated on the landscape, with an example being mountains. Per Walker’s translation, “using triangles carries out 2 objectives-gives players a choice as to whether to go straight over the triangle; or around, and it obscures the player’s view, so designers can utilize them to surprise players, make them wonder what they’ll find on the other side.” Variation can also be added to these triangles (which the designers used in the case of collectibles, like Korok seeds), and Nintendo also used three different sizes of the triangle as a model for what the player will see or experience:

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

“The largest are landmarks that serve as visual markers, the medium-sized triangles serve to obstruct the player’s view — whatever is behind them— and the smallest triangles serve the tempo , be it to change whatever buttons the player is pressing or for more concrete play.” Meanwhile, the game’s towers (among its only waypoints) were initially used to enforce linearity, which contradicted the team’s design goals and did not appeal to players. So those structures were relocated to instead inspire players to explore off the beaten path and become sidetracked, reinforcing the game’s infinite play loop.

Nintendo’s goal with Breath of the Wild was to create myriad permutations of possible interactions between the player’s actions, items, landscapes, and reactive objects, resulting in a complex experience where “countless events occur, and the player can freely create solutions,” or "active multiplicative” gameplay.

This results in multiple solutions to in-game challenges, rewarding the player’s ingenuity and spontaneity. And while some of those interactions were small and inconsequential (for example, the fire from a torch turning an apple into a Baked Apple) they were also often unpredictable, adding surprise and charm to each discovery. My favorite? Turning Chuchu Jelly into an elemental version by shooting it with a Rod.

Sure, a lot of players didn’t appreciate that the weapons in Breath of the Wild had limited durability. In the previous games, you never had to worry about them breaking at all. But if there’s anything that the Legend of Zelda games could be accused of, it’s discouraging variety. In the past, tools were niche-use items for specific puzzles or enemies, and weapons were more of the general type. Often, once you found your preferred sword or arrow type, you were good for the whole game. Breath of the Wild never lets you get too comfortable and forces you to strategize by adapting to and becoming proficient with all the different weapons you find on the fly, highlighting how important it is to actually support and accommodate variety if you want players to actually take advantage of it.

Continuing from our previous point, sometimes resource scarcity is a good thing. The cooking feature in Breath of the Wild not only provided many opportunities for hunting and gathering, but it also kept players on the move and engaging with the environment, encouraging creativity and exploration. While this may be tedious in other games, mixing and matching ingredients to find the best recipe and max out its boosting effects was fun, and Link's cooking animations and the mouthwatering appearance of each completed dish added a sense of reward. Watch senior editor Bryant Francis and Game Developer alumni Kris Graft debate this and other points in their Twitch stream discussion from 2017.

If you want to study other aspects of Breath of the Wild’s technical design, be sure to visit the GitHub summary of the CEDEC 2017 talks, which covers:

the UI of Breath of the Wild and the thought process behind its graphics, font, design and animation

the game’s open-air audio design and why Nintendo went with atmospheric events over a looping score

their three-step approach to project management, with a look at their technical artist pipeline, and how they streamlined the QA process

a dive into their in-game bug-reporting system

You’ll also be enthralled with the overworld note-leaving system that the team used to organize their to-do tasks in the game on both a micro and macro level.

There’s also a can’t-miss 2D Bread of the Wild prototype, done in the style of the original game, depicted in the GDC 2017 talk Breaking Conventions with The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild.

And hey, while you’re at it, maybe check out this Nintendo of America video of Breath of the Wild devs talking about what they loved most about the game, just because it’s cute and fun.

For more analysis, be sure to check out these blogs from our community:

An analysis of the game’s open world design by Nic Phan, entitled Breath of the Wild Open World Analysis: Gravity to Go Forward.

A deep dive analysis from Eloi Duclercq entitled The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild from a UX point of view.

And some thoughts from Jon Irwin on one of Breath of the Wild’s most dramatic changes to the Zelda formula, entitled Link can jump in the latest Zelda. Here's why that's a big deal.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like