Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Too often, graphic adventure games can suck. But they don't have to.

[this article by Ryan Henson Creighton is re-posted from the Untold Entertainment blog, which is awesome]

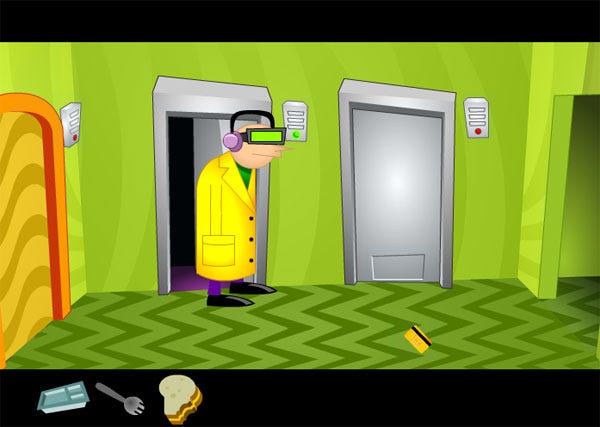

It's no secret that i love graphic adventure games. They're the reason why i'm in this industry today. i've worked on a number of them (including Jinx 3: Escape from Area Fitty-Two, Heads, Summer in Smallywood, Sissy's Magical Ponycorn Adventure, and the upcoming Spellirium), and have devoted considerable resources to developing UGAGS: the Untold Graphic Adventure Game System (our company's answer to SCUMM), which has helped me to build that list of games. i've also written lots of articles about the genre (check the "Further Reading" section at the bottom of this post!)

The UGAGS oeuvre to date.

Call me a snob, but i like graphic adventure games for the mere fact that their characters have something going through their minds other than "shoot". i like that their plotlines boil down to more than just "kill mans" or "glorm points". And i like standing in a room in a graphic adventure game, alone with my thoughts, without having to worry about time limits or pyrotechnics wizzing past my face every few seconds. As Monkey Island creator Ron Gilbert put it during his Maniac Mansion postmortem at GDC 2010,

"The magic of an adventure game is staring at the screen, wondering what to do next. It's that quiet contemplation."

With the massive Kickstarter windfall for an unspecified graphic adventure game, Tim Schafer, Ron Gilbert and Double Fine proven that there is still a market and a fondness for the genre. That being said, there are some legitimate and persistent problems with graphic adventures. Here's a short list of the most common ones, and my thoughts on ways in which we, as graphic adventure game designers, can fix them.

True, it's magical for a video game to leave you guessing, instead of ramming a tutorial down your throat at every turn like most modern games do. But if you get stuck enough, long enough, that magic turns to salty poop and you really just want to get unstuck. If the only recourse for the player to get unstuck is to consult GameFAQs, you've failed as a designer. i've abandoned numerous graphic adventure games because i "cheated"; solving the rest of the game became a lot less enjoyable and i gave up, thoroughly racked with guilt-derived stomach cramps.

Throw the bridle on the snake to turn it into Pegasus. Why oh WHY didn't i think of that??

But if the game gives you a way to cheat, or to get a hint, it's somehow legit and i don't feel as bad. It's game-sanctioned cheating - a subtle, but powerful, difference. Modern graphic adventure games like Machinarium use an in-game help system.

Machinarium puts you through a twitch-based minigame before giving you a hint.

Another interesting way to handle this is to design your game such that the player can never get stuck. You just plod through the game, missing cues left and right, until you crash into the inevitable, unsatisfactory ending. But if you're keen and clever and aware, you can strike out off the beaten path, do all the difficult things, and get a much better ending. Games that use this approach include Kult/Chamber of the Sci-Mutant Priestess, The Last Express, and The Colonel's Bequest.

It's possible to coast through The Last Express without ever figuring out whodunit, whatsgoingon, or whosthatladywiththegun

One year at GDC, i heard a woman speak who was an advocate for female gamers (if you know her name, speak up!) Her heartfelt conviction, ladies, is that if you buy a game and you can't access all of the content on the disc because the designer won't let you, take the game back to the store and ask for your money back. Years ago, this struck me as utter blasphemy ... and yet here i am, developing Spellirium so that all of the challenges are no-fail, and you can sail through the game from beginning to end without the game requiring you to be awesome. It's awesome-optional. But for those players who DO excel, there are treats and rewards.

When graphic adventure games moved from using text-based parsers to entirely mouse-driven interfaces, they were distinguished from their parser predecessors by the term "point n' click". This term was later twisted to the pejorative "hunt n' peck" because numerous graphic adventure games, in lieu of offering clever and interesting puzzles, would hide important items in a 2-pixel-square hit area so that the player's only recourse was to slowly scan each and every location by trawling the cursor slowly over the screen in rows, like he was a human dot matrix printer. Listen: i could be a very rich man today if i had built HOGs (Hidden Object Games). They're immensely popular. But the entire genre is based on this one terrible flaw of graphic adventure games. HOGs, by definition, are pixel hunts. i can't do it. i just ... no. You know?

Finding the pair of tweezers in the messy bedroom is not my definition of a fun time - it's my definition of every goddamn day of my life

How do you fix this problem? The obvious answer is to make bigger hit areas. But i've seen other games go even farther. Telltale's Back to the Future on the iPad enables you to multi-finger diddle the screen to make all of the location's hotspots light up. Like the "every player's a winner" strategy i mentioned above, this seemed too broad and too giving. i mean, the game might as well be playing itself at this point, right?

The more i thought about it, the more i thought back to adventure games where the only reason i got hopelessly stuck was because i didn't know that that part of the screen was an exit to another location. The joy of an adventure game should be in being a character, playing through a story, and feeling clever for solving some problems - not in discovering that you can click that plant that looks like it's part of the background.

One of the most despised phrases in the annals of graphic adventure gaming is "you can't do that -- at least not now" which, if you've played through the King's Quest series, you've read at least a few hundred times in your miserable existence. Graphic adventure game cock-blocking occurs when the designer has not thought through enough interaction possibilities, and has thrown up a vague, generic message to the player. This is essentially computer programming error code handling, with messaging that's barely more helpful than actual computer programming error codes.

The reason why cock-blocking is so common is that it takes a lot of effort to account for every possible thing the player might try to do. Indeed, for games with a text parser, it's nigh-impossible for the designer to anticipate every single combination of words, including gibberish, the player may hurl at the parser. With verb-based adventure interfaces like the one in Maniac Mansion, the permutations shrunk significantly.

Sidenote: this is the exact moment in Maniac Mansion when the majority of players wet their pants.

A corollary to item use cock-blocking is a situation where the player tries to use a long, rigid item to pry something off another something, but he doesn't use the correct long, rigid item that the designer was thinking of. Stick - no good. Pole - no good. Broom handle - ding ding ding! Here's how graphic adventure developer and wittily snarky pundit Ben "Yahtzee" Croshaw puts it in his Depressingly Common Adventure Game Design Flaws series (the rest of which i've avoided reading, for fear of being wittily snarked at for plagiarism):

"The best game I have ever played for intuitive puzzles has to be the aforementioned Zak McKracken And The Alien Mindbenders. There's a whole horde of inventory items in Zak McKrack, and I could give a thousand examples of puzzles with several alternative solutions. How about using a monkey wrench to wake up the bus driver, but also being able to do the same with any other long, hard item in your inventory, AND having the option of waking him with a merry kazoo interlude instead? You can use a butter knife to get a cashcard from under a desk, but you can also use any of the several pieces of paper, all of which can also be used for drawing maps. Then, when you try to lever up floorboards with the butter knife, it's obviously too flimsy, and you get left with a bent butter knife. Having so many possibilities and so many avenues to explore not only constantly rewarded the player's intelligence but provided the vital encouragement needed to make them push through to the very end."

Before Spellirium, UGAGS games got right around this problem by not offering any item interaction whatsoever. If you clicked on a hotspot, and you had the inventory item that interacted with it, you automatically used the right item. In Jinx 3, if you were carrying the spork, you could tap on the prison wall with it. If you held the banana, you could flush it down the toilet to create a flood. This covered off any puzzle design blunders that i may have committed. Left to his own devices, would the player really know he should tap on the wall with the spork? With auto-item use, i never had to worry about it.

Why force the player to say "use keycard on door" when the interaction is obvious?

Since you can use items on hotspots in Spellirium, i've developed a new system to minimize cock-blocking. Given a hotspot like a locked door, i can obviously define what happens when you use the iron key on it. But i can also list other items the player might try to use, like the metal pole (to bash the door down?), and i can have Todd respond in kind: "This metal pole is too flimsy to bash the door down." That makes the player feel good, because i'm acknowledging that he had a good idea, and it's so much more satisfying than "i don't understand that" or "i can't do that."

The next line of defense is generic item commands. If i haven't written an item-specific response, the logic falls through to the hotspot's generic response, like "i can't use that to get through the door." This is a little more frustrating than a specifically-written response, but at least it's something. One game that i noticed did a LOT of work to provide an item-specific response for every imaginable item/hotspot combination is The Whispered World. Very well done.

A very common and frustrating mistake that adventure games make is to send the player off in search of something that is represented in the background artwork, but the background element is not wired for interaction. While it's not a graphic adventure game, i was recently playing the abysmal Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword, and a character asked me to go find a piece of paper - "ANY piece of paper". The setting for this fetch quest was an academy packed to the teats with books, parchments, scrolls and papers of every imaginable kind ... but i couldn't pick any of them up. i had to go hunt down the exact piece of paper the game wanted me to find.

Don't surround the player with non-interactive books, and then ask him to find "any" piece of paper.

A related problem is the too-damned-interesting-background-art error. This is where you have something in the background that every player clicks on, but you haven't written a description for it. And the player figures there MUST be something up with that video camera hidden in the plant. But there's not.

In an attempt to address this, we're developing a heatmap system for Spellirium where we can analyze players' clicks. If we notice enough heat on a particular area of the screen that we haven't wired up for interactivity, of if there's a hotspot that gets clicked non-proportionally to its relevance, we know we have some splainin' to do to the player.

Heatmaps: they're not just for Halo any more.

Again, while it's not a graphic adventure game, there's a lot we can learn from the steaming pile that is Skyward Sword. Throughout the game, non-player characters ask you to make a choice. "Link! Will you save my kitten from the tree?" You know that, as the hero, you kind of have to save the kitten. Yet you're given the option to say "No." And when you do that, the story does not move forward. You MUST re-engage the NPC. You MUST say "Yes" this time. You MUST save the kitten. What was the point of the interaction, other than providing the illusion of interactivity?

The reason why designers do this is, of course, to save work - a LOT of work. If, whenever you made a binary decision, the ramifications spun off wildly into two alternate timelines, you'd be building an impossibly large game. But i can't stand it when it's obvious during a conversation that no matter what i "choose" to say, the conversation is always going to go a certain way.

The solution is a trick of good creative writing. It's fine for the conversation to always lead into the same funnel. It's not fine for the player to know that. Through clever writing, you can make the player think he's affecting the conversation, even when he's not. If you're crafty, you can even give the player a binary decision with two seemingly opposite inputs, but steer them both around to the same outcome. Consider this conversation snippet from Spellirium between Todd and Lorms:

Todd:

Uh ... okay. You can tag along, I guess. [C1]

It's probably better if I go alone. [C1]

[C1] (Todd walks to the edge of the screen)

Lorms: Where are you going?

Todd: I dunno. That way?

Lorms: Do you have a plan? Do you even know how you're going to find your friends?

With one option, the player decides that Lorms can come with him. With the other option, the player decides to go it alone. Lorms is one of Spellirium's main characters. Make no mistake: he's coming on the journey. But despite what the player chooses, he feels like the game is honouring his choice, and the conversation and actions that flow from that point feel natural - even if the player chooses two completely opposite responses.

The graphic adventure game genre is far from perfect, but there are many things we can do as savvy designers to account for the crimes perpetrate on players past. We have been bad, but we will atone. But will it be enough to resurrect a genre that's been on life support for the past twenty years?

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like