Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

We reached out to developers to ask for their favorite examples of great boss fights that are worthy of close study. They tended to favor the classics.

They're extremely common in video games, but boss fights are hard to do well. Indeed, many designers stumble on one aspect or another when crafting their big encounters — perhaps leaning too hard on the need to challenge the player, or maybe failing to incorporate (and subtly tweak) the mechanics learned and practiced in the lead up to that fight.

There are many potential points of failure, but you can avoid them all if you take heed of the lessons presented by other games past and present. To that end, we reached out to developers to ask for their favorite examples of great boss fights that are worthy of close study. Those who responded tended to favor the classics of yesteryear, in testament to the fact that newer is not always better. Here are their suggestions.

The Metal Gear Solid games have long had memorable boss fights — be it Psycho Mantis in the first game, Fat Man from MGS2, or Liquid Ocelot in Guns of the Patriots. But Naughty Dog designer Matthew Gallant thinks The End from Metal Gear Solid 3 is the best of the bunch. "It's a sniper duel in a huge jungle arena," he explains. "The End is sneaky and camouflaged, forcing the player to outwit him. The fight creates a very palpable sense of being hunted."

Gallant calls it "the most mechanically-rich boss fight" he's ever encountered, praising the assemblage of tools and mechanics it draws upon. In particular, the player can use binoculars to search for the glint off his sniper scope, find footprint trails with thermal goggles, use a directional microphone to listen for breathing or muttering, kill (and eat!) The End's spotter parrot, and sneak up on him to use the game's "hold up" maneuver — which causes him to drop a special camouflage and non-lethal tranquilizer gun.

And as if that's not enough, the player can avoid the fight altogether by shooting The End with a sniper rifle after an early-game cutscene. Or, even more cleverly, it's possible to play on the information that The End is close to death. "If the player saves during the boss fight and loads their save more than a week later," explains Gallant, "then they find that The End has died of natural causes."

Takeaway: If your game has a rich set of mechanics, there's nothing to say you can't incorporate them all into a boss fight, and it can heighten the tension if you make it as much a battle of wits as of brawn.

The oft-imitated SNES classic Super Metroid bears all sorts of design lessons in weapons, levels, difficulty curves, and more, but for Nefarious creator Josh Hano it's especially worthy of study for its boss fights. He points to the Mother Brain encounter, in particular, for its use of aesthetic and mechanical cohesion.

"Namely, when Brain destroys the now grown-up metroid you 'adopted' in the opening cut scene," explains Hano. "If you're at all invested in the story you want to absolutely trash her for it. The game creators knew this, and so they gave you the ultra laser, a new ability that can absolutely wreck Mother Brain. Mechanically it's a simple point and shoot laser, but it feels completely satisfying to use."

Takeaway: Give the player an emotional reason to hate your boss and they'll find it all-the-more rewarding to take them down.

Hano also praised Super Metroid's Draygon fight for its inclusion of a secret trick to end the fight early. "He has a move where he grabs you, and flies around the room with you," says Hano. "You may use your grappling hook to grab onto a sparking bit of broken machinery and channel electricity into the beast. Which really felt like you were outsmarting a much tougher opponent because if you don't use that secret, he is a very difficult fight."

Playtonic Games director and Rare alum Gavin Price agrees. He loves that it allowed the player to turn the arena against the boss, especially since "arenas usually always favor the boss and load the odds in their favor." Like the Mother Brain fight, this also tied into a deeper theme. "The boss fight found a way to still encourage the game's core (and more passive) theme of experimentation and exploration amidst a mechanically-challenging fracas," says Price.

Takeaway: Keep your boss fight designs consistent with the game's underlying themes as well as its mechanics. And if you've encouraged experimentation elsewhere, reward it here.

Battletoads may be best known for its extreme, ultra-punishing difficulty, but the NES side-scrolling beat-'em-up was also filled with ambitious and clever design ideas. Price speaks highly of the boss fight at the end of the first level. "This boss looked to be the normal affair with a brief glimpse of it at the end of the level as a huge leg plunged down," he explains. But then the game switched things up and changed from the standard side-scrolling viewpoint to the boss' point of view.

"With a very novel and fun twist that shows that regardless of mechanics and cameras the game usually relies on," says Price, "a boss can be its own mini-game like experience and break up the regular gameplay with a fresh take on things."

Takeaway: Variety is the spice of life — a change in perspective or a new twist on a core mechanic could be just the spark to get the player excited about tackling the next stage of the game.

Portal spends the entire game building up to a big fight against its malevolent AI antagonist GLadOS. GLadOS taunts and teases and betrays the player repeatedly under the guise of innocent tests that'll be rewarded upon completion with cake. When the player finally reaches GLadOS, they're primed for battle, and after a brief non-violent confrontation things quickly escalate. The game then cleverly channels the film 2001 and, as game design consultant Mike Stout (formerly of Insomniac and Activision) noted in his 2010 feature on boss battle design, it breaks from convention.

"Instead of a transformation, a false defeat, or anything like that -- GLadOS simply taunts the player and invokes the idea of 'death' [by referring to the companion cube the player incinerated early in the game]," Stout wrote. It's an emotional priming for the big test, as GLadOS goes all-out to kill the player, ahead of an even bigger final payoff — explosions, fireworks, and a song (but no cake).

Takeaway: A boss fight is a story within the larger story of the game, and as such it should have beats that build anticipation and charge emotions. Also, a few well-placed words can have more impact and raise the stakes further than a larger-than-life physical transformation.

Super Nintendo boxing game Super Punch-Out is nothing but boss fights, but Price believes each and every one of them is worthy of close study. "Super Punch-Out manages to find 16 unique and brilliant ways to test the players pugilistic powers based on very few actual moves available to the player," says Price. "Many games struggle to do this once."

The secret is in the character animations. "Each animation’s speed and sequence of events are distinct and very well thought out to be able to equip the player with all the visual information they need to overcome the challenge," explains Price. Watch opponents' animations closely and you'll get clues to help you predict when, where, and how they'll attack or become vulnerable, and you can devise strategies accordingly. It's an important lesson, Price argues, as Super Punch-Out shows that even a single battle mechanic can be challenging and engaging if executed well. Moreover, by providing this kind of visual information, the designers managed to avoid unnecessary player confusion and frustration.

Takeaway: One well-executed, carefully-tuned mechanic is all you need, but either way it's vital to have clear visual feedback that not only shows the effects of a player's actions but also provides clues as to where the boss' weakness lies.

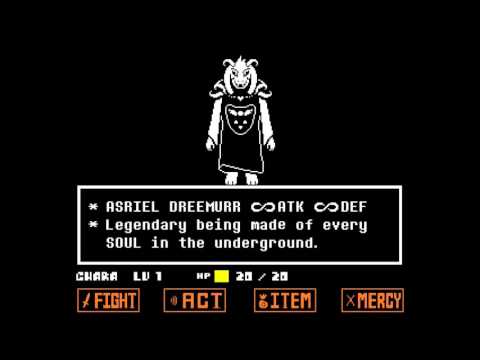

Torment: Tides of Numenera lead area designer George Ziets points to indie RPG Undertale as his favorite example of great boss fight design. He believes that combat (along with every other part of a game) is an opportunity to reveal story and to offer the player options that would change outcomes with characters. Ziets says that Undertale does this especially well. "The game was great at creating layered characters with hidden motivations beneath their (often humorous) outward behavior, and the deeper characterization was almost always revealed during the combat sequences," he explains.

More mechanically speaking, its boss fights are puzzles, always with more than one solution, and usually incorporating dialogue, items, and the opportunity to show enemies mercy. "It is up to the player to discover how best to resolve them," he explains. "And the most obvious approach of killing your enemies is never the ideal result."

Ziets suggests that nearly every Undertale boss fight is worthy of study, for the imaginative variation in mechanics and use of humor to make bosses more sympathetic characters. But he picked a few examples to highlight: in one battle, against the Royal Guards, selecting the "clean armor" option reveals unrequited romantic feelings between them and unlocks a non-violent, happy ending to the fight; the "So Sorry" encounter, by contrast, disguised character interactions in the form of fights. Other battles revealed character and personality. "In the encounters with Metaton and Alphys," says Ziets, "the player could learn about Alphys' crush on Undyne and her tender feelings toward her robotic creation, Metaton, despite his dangerous behavior."

Takeaway: Boss fights present conflict between characters, and that conflict need not necessarily be violent if it's about developing relationships or empathy or furthering a story beat.

When it comes down to it, boss fights are about testing mastery, rewarding progress, and furthering the story. The best examples put a fresh spin on a game without alienating or unduly confusing the player, and they come with clear motivations — you don't just fight a big baddie because they're there.

Be willing to play with your player and their expectations, to present conflict and characters in a new light, but remember they still need to be consistent both thematically and mechanically — otherwise you risk losing the players who can't or won't put up with any radical departures from the systems, ideas, and motifs you've spent the rest of the game establishing.

You May Also Like