Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Which strategy titles offer instructive examples of good design that every developer could benefit from? We asked several industry luminaries for their picks.

Strategy games, like a number of genres buoyed by the rise of independent development and digital distribution, have been enjoying something of a renaissance lately. But this boom of recent titles didn’t appear wholly formed out of the ether. These titles owe a huge debt to a decades-old foundation that rarely gets explored or given the credit it deserves.

With this in mind, we reached out to a number of current strategy developers and asked them to name some of the old titles (and unsung modern classics) that influenced them, games that they think other developers could draw inspiration from. Here are a list of their picks, and some insights from industry luminaries on the special lesson that each game imparts.

What strategy titles do you think offer a master class for game developers? Let us know in the comments below!

(For more along these lines, be sure to check out Gamasutra's lists on instructive uses of procedural generation,AI, progression and event systems, procedural generation, and crafting.)

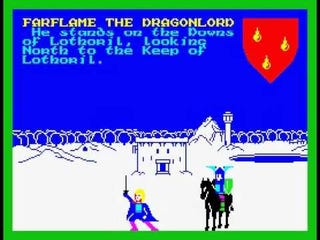

The Lords of Midnight is one of the earliest examples of a grand strategy title in the contemporary sense. This 1984 ZX Spectrum release showed what was possible when you pair strategy game staples like armies and territory control with unique personalities. (It has since been ported to C-64, MS-DOS, WIndows, iOS and Android.) Pitting a band of four heroes against the aptly named villain Doomdark the Witchking, The Lords of Midnight was one of the first hybrids of strategy and role-playing (with some adventure elements sprinkled in).

It made a very strong impression on Henrik Fåhraeus, game director at Paradox Interactive.

“This fantastic old game (and its sequel, Doomdark's Revenge) by the late and great Mike Singleton still stands out as something totally unique,” says Fåhraeus. “It’s a first person[!] strategy game, where great lords moved around the land with their armies and tried to recruit others to their cause depending on their respective personalities and existing loyalties. It is pretty dated now, of course, but I'm sure the basic concept still has untapped potential...I used some of these ideas in the Crusader Kings design.”

TAKEAWAY: Give life to the resources and accounting endemic to strategy by imbuing your game with personality, and avoid the pitfall of becoming a number-driven grind.

Great game AI has been a back-of-the-box bullet point for decades, but more often than not it’s stilted, awkward and--worst of all for strategy games--easily exploitable. But when it is done right, it not only makes a game more challenging and success more rewarding, it makes it much easier to get immersed in the world a game is simulating. Alan Emrich of Victory Point Games looks back at titles like Reach for the Star: The Conquest of the Galaxy by the industry pioneer Roger Keating for examples of AI design done right.

Reach for the Stars is the first commercially published 4X strategy game, and it established many of the conventions of the genre. Emrich is the guy who coined the term 4X, and he worked on several Masters of Orion titles. He speaks of Keating's classics with something akin to awe.

“Roger knows how to build tough AI for these and other games he has worked on,” Emrich says. “His games are a symposium on how a player and an AI can interact. Check it out if you want your head handed to you versus an intelligence that is demonstrably ‘playing cricket,’ but is just a whole lot better than you.”

TAKEAWAY: Keating’s classics walk a difficult tightrope, balanced between believable intelligence and impossible difficulty. The key is writing fallable machines, AI opponents that believably mimic human players.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Strategy games are generally considered to be the dull, plain cousins of slicker action games. It’s a nasty stereotype that’s often borne out by hardcore grognard fare, but one that's thoroughly repudiated by games like Homeworld. Marco A. Minoli of Slitherine Ltd. points out that this venerable scifi RTS was not only intellectually satisfying but also jaw-droppingly gorgeous, as visually appealing as anything else available when it was released in 1999, which added immeasurably to players' immersion in its farflung universe.

“It is really a game that brought a totally new approach to real-time strategy, and to innovative visuals altogether," says Minoli. "When it was first announced in 1999, players were not only captured by the 3D graphics and gameplay features, but also by the really iconic and innovative visual style, a first for strategy games at that time.”

TAKEAWAY: A little flash can not only make your game more appealing, but add verisimilitude.

While there’s definitely a place for style and slick graphics, Minoli also points out that with a strong enough core of entertaining gameplay, graphics can be a secondary concern. Substantive and engaging gameplay will always be the beating heart of the strategy genre. Nothing exemplifies this like Introversion's visually simple but utterly nervewracking 2006 game Defcon. This high-level strategy sim captures the tension and horror of nuclear brinksmanship at the paranoid peak of the Cold War. The simple graphical interface, reminiscent of the classic 1983 film War Games, somehow made the stakes seem even greater.

“The first game made by Introversion was a real stunner,” Minoli says. “It was one of the first 'indie games,' coming out of nowhere in the new era of development. It took advantage of digital downloads when very few companies were mainly distributing online. And it became famous entirely thanks to its gameplay. Defcon showed the world that a developer with great ideas could create a success story even without huge budgets.”

TAKEAWAY: Ensuring players have fun should always be your chief concern; anything that doesn’t add to that is expendable.

There’s a temptation in design to embrace the kitchen sink approach: instead of trying to predict what players will enjoy, just throw everything you can think of at them, and something is bound to stick. But, according to Scott Brodie of Heart Shaped Games, sometimes simplicity is best, as in Oasis. This 2005 turn-based strategy title by Mind Control Software casts players as an Egyptian ruler looking to expand your sphere of influence as you seek the 12 mystical glyphs that grant unimaginable power.

“Oasis (or Defense of the Oasis, as the mobile port is known) has been a big influence for me," says Brodie. "Besides being important as one of the first modern indie strategy games to break through, it is masterful in drawing gameplay depth from a small set of systems and inputs. A lot of strategy games operate at an 'epic' scale, with tons of game pieces and resources to manage. Oasis achieves the same depth with far less. I also just love some of it's smaller design choices, like how it presents temporary power-ups as characters that join your leader, or how it uses a few simple audio and camera tricks to turn bouncing dots into dramatic battle scenes. It's just a memorable, well-crafted game that could get overlooked because of its roots as a casual game.”

TAKEAWAY: Overcomplicating and bloating your game with unnecessary content and mechanics often has the opposite of the intended effect and scares players away rather than attracting them.

Games that do a handful of things exceptionally well can be far more compelling than games that do many things middlingly. Soren Johnson of Mohawk Games points to Unity of Command as an excellent example of this. This 2011 operational-level strategy wargame doesn’t attempt the impossible task of covering every aspect of a global conflict like WWII, but instead tightens its focus to a more manageable scale. It zeroes in on the gritty realities of waging war, from changing weather to logistics, and sprawls across the entire Eastern Front of World War II.

“Few strategy games are brave enough to be about one thing, especially when that one thing is supply lines!" says Johnson. "However, by doing so, Unity of Command avoided the fate of most WWII computer wargames, which tend to muddy their design by modeling as much of the conflict as possible. Every aspect of the game emphasized the importance of maintaining a supply line during a battle while, abstracting almost everything else about Eastern front battles. As a nice bonus, the supply mechanics enabled legitimate comebacks by punishing an over-aggressive attacker who allows his or her troops to get cut off or encircled. Most strategy games struggle to make comebacks even possible, let alone a natural result of the core rules.”

TAKEAWAY: Focusing on your strengths means your best foot is always forward, and that you have more time to develop ideas you know will work, rather than devoting resources to concepts that may not even make it into the final version of the game.

Emrich felt it was vital to acknowledge strategy’s roots in tabletop experiences, and says that videogame designers could learn a lot from physical games that can't rely on interactive tutorials or user-friendly avatars to make sure players grasp all of their systems. One title that stands out to him is the recently released 3rd edition of Dawn of the Zeds.

“Dawn of the Zeds demonstrates the fine art of documentation writing for intricate, sprawling subject games," he says. "Its rules are encoded with writing discipline, its examples are incredibly illustrative of the nuanced interactions of gameplay, and its organization works well, both when first encountered and read like a book, and again when later referenced for a quick answer.” [BONUS RECOMMENDATION: Emrich says that the 1999 game Totaler Krieg offers a similar master class in clarity.]

TAKEAWAY: Use writing intelligently, sparingly, and make sure the text is good clean copy that conveys what you need to as simply as possible.

You May Also Like