Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

This War of Mine seen from the perspective of one of the designers. What design features make it stand out how they contributed to the game's success? What can a game designer learn from it?

I spent the last two years of my life as a part of the great project which has been This War of Mine. I’ve been involved since the very beginning, mostly as a game designer and partially as a writer. Now, that my adventure with both This War of Mine and 11 bit studios is over, I let myself look on a game from a distance. I’ll do my best to analyze those key design features that I think did the most for its benefit. These are the things that I will remember for my future projects.

I had a pleasure to have my face and body used for one of the characters.

I had a pleasure to have my face and body used for one of the characters.

(Mind that the article is not an official statement of the company, it’s my own opinion, a view on the game seen from one of the designers’ seat.)

It was clear since the beginning that we’re going to make a game that is unlike any other. It was meant to be, as far as we knew, the first game about the civilians in the warzone, which demanded a different than usual approach to its design. There just wasn’t a tested game design formula for this kind of project, because this kind of game never existed. So the key was to find the ways to symbolize the real problems of such events as a game mechanics in respectful and credible way, avoiding “gamisms” as much as we could.

If I was to guess, before the release, how the game’s innovation will affect its popularity, it would be a huge miss. Because of how different TWoM is, both in terms of the theme and the gameplay, personally I was seeing it as a niche game, that will be appreciated only among a small crowd with discerning taste. Thankfully I was wrong.

… Or perhaps I was right about the discerning taste, but I underappreciated the size of the audience. This mistake taught me that the players still like to be surprised. That they don’t solely crave another Spectacular Action Game 6 HD, but will also appreciate new ideas. Why won’t we give them a fix?

Let’s face it, you can’t make better Call of Duty than Call of Duty. But perhaps you can afford to try making better This War of Mine than This War of Mine. Or a one-of-its-kind game that will automatically become… well, the best of its kind. What I mean is that the more derivative your design is, the bigger the competition and thus the harder it is to stand out.

Papers, Please is a one-of-its-kind game done by one man and a great success.

Papers, Please is a one-of-its-kind game done by one man and a great success.

Of course This War of Mine is an usual example and no matter how innovative is the design, it won’t GUARANTEE you such a success. Still, my take is that the smaller the game, the more it should look for an innovation (or a niche) and TWoM reassured me about this. The last years were rich in successes of relatively small games that seem to support this idea. Like Papers, Please, which was a great inspiration for TWoM. Or like Vanishing of Ethan Carter, FTL, Gone Home and Thomas Was Alone, to name a few.

I think that the only way for a small developer to fight a blockbuster is to compete in a different category.

There’s one particular ingredient of This War of Mine that I started to really understand and appreciate when the game was already released and the players started to tell the stories of how they playthrough looked like. Then I realized that the strongest storytelling device the game utilized was… well, it’s awareness of being a videogame. But a videogame, where game mechanics not only don’t conflict with the narrative, but they’re used as its fundaments.

Steam reviewers often tell parts of their playthorughs as stories.

(http://steamcommunity.com/profiles/76561197993844742/recommended/282070 )

I don’t think that games, in order to become stronger as narrative medium, need to reject what they are and try to incorporate more from other media, such as cinema. In my opinion it’s the opposite – I think they need to embrace what they’re good at and use it wisely to create stories that couldn’t exist elsewhere. In short, it’s about making sure that decisions the player makes as a part of the game (and their consequences) are meaningful for the narrative. The games were about making decisions long before branching storylines of The Witcher or The Walking Dead. Whether you jump or fall, slash or block, shoot or miss, drive straight or turn – all those little moments that make up the gameplay may become a part of an interesting narrative. More – they can SHAPE the narrative, and that’s an unbelievably powerful feat, that film nor literature cannot do.

It’s not necessarily obvious. When I play Uncharted, I don’t feel that killing an enemy number #4859 with my machinegun is a part of the story where I’m animating this witty adventurer. My goodness, he’d just kissed a girl in this brilliantly crafted cut-scene, and now he’s some kind of psycho?! For me the revelation that the things can be done differently came when I encountered Papers, Please. It’s really a “gamey game”, with very visible core loop. But the decisions you make are part of the monotonous protagonist’s life and they visibly affect it. They tell his story. Your story.

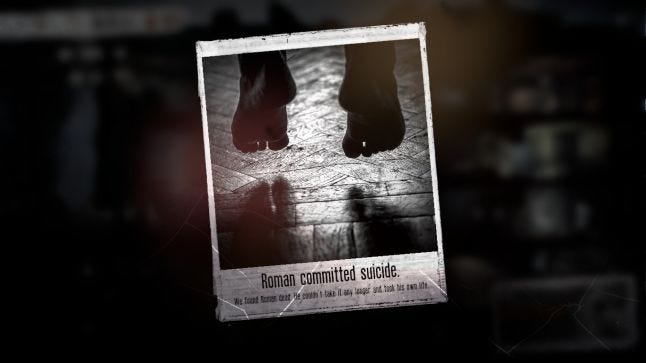

Of course not your failure as a game designer, but the player’s, as a character in the story. There’s a particular characteristic of This War of Mine that, I must admit, wasn’t intentionally planned, but emerged from other game design decisions. I noticed it when I was watching Indie (Dan Long, http://www.twitch.tv/Indie) streaming a preview version of the game on Twitch. The playthrough was fairly typical, giving Indie enough space to joke around with his audience. Until the things got bad. A character died, than another, ultimately leaving the remaining member – Bruno - of the group lonely and broken. The game ended when Bruno committed suicide. Seeing Indie’s reaction I realized that his failure was the most interesting thing in this playthrough.

If you consider your favorite stories, for example in film or literature, they don’t always revolve around success. The character may become hurt or defeated, also you usually don’t ask a refund for a book just because the main hero dies at the end. Meanwhile the games accustomed us not to treat the failure as a “real” part of the story (unless it’s a scripted, plot-driven failure). Back to the old Nathan Drake (nothing personal, I still love those games) – if he’s suddenly taken down by the enemy #4860, you probably curse and reload the checkpoint like it never happened. Because if it did, it’d be a really shameful way for a hero of a good story to end his life.

If we assume, like I previously argued, that the player’s gameplay decisions and their consequences may be treated as a fabric for the narrative, so should be with his failures. They should be given enough weight and acknowledgement to become a real part of the story. And preferably an interesting one.

One of the most important things I’ve learnt during my whole time at 11 bit studios (3 years) is how to prototype. And that you won’t get away without doing prototypes, at least at the beginning of the project.

There’s much that has been said about prototyping games, and I certainly recommend to look it up if you haven’t done any prototype yet, but basically it comes to one thing: making your design work and test it BEFORE it lands in the game. My biggest mistakes came from being overconfident and assuming that things will work just because they looked good “on paper”. In reality, sometimes the simplest prototype is enough to discover the problems. And by “the simplest” I mean that it doesn’t even have to resemble the real game – it can be a mockup in Paint, simple board game, a level built in Lego, a spreadsheet, a simple mingame written in Basic... Just use the fastest method to test your current problem.

When we started to work on TWoM, we made a several prototypes for the crucial systems, each with a few iterations. For example the characters’ needs system was first done as a series of spreadsheets, while combat and crafting were tested as small applications done in C# by the designers. Only after we got the fundaments right, we build a bigger prototype combining all of it in something that looked like a very rough version of the game.

One more thing. I’m speaking from a design standpoint, but similar principles can be applied to other aspects of the game as well, like technical or artistic decisions. Make the simplest version first to check whether it works. Iterate till it does.

Trying out the prototype by yourself is a good idea, but it’s better to give it to someone else. The same applies to bigger and more advanced chunks of your game, ultimately even the whole game. And at some point it might be the best to organize formal, structured playtests to assess the players’ experience from the game. Fortunately this was always a part of 11 bit studios’ ethos and had been done consciously throughout the development of This War of Mine. Knowing how much was improved using the feedback from the tests, I’m quite sure that otherwise the game wouldn’t be nearly as good.

How to do it is a topic for at least a separate article. My take is to do it as early as possible (starting from showing the first prototypes at least to your family and friends) and as often as possible, making sure you’re still on track after every major change in the game. However it doesn’t mean it cannot be overdone – the biggest trap is being uncritical about the players’ feedback. Don’t let them decide, it’s still your game. I personally prefer a doctor’s approach: ask how they feel, but not what remedy they’d like to take.

There’s no one recipe for the game’s marketing, but nowadays contacting people that can show it on YouTube and Twitch is without doubt worth considering. It’s been done with TWoM and went really well, resulting with many great videos that attracted many viewers interested in the game.

But I’m afraid it won’t work for any game. Some can be spoiled by “let’s play” video or a stream, especially those that rely on a linear plot. This War of Mine seems to be different – people, after watching, still want to play. This property wasn’t planned in the game’s design, but from hindsight I can speculate what aspects of it worked here. I think it’s because of the importance of the personal attachment to the events on screen and the ability to build the story on individual decisions – no matter how many playthroughs you see, you won’t see everything. Because you won’t see YOUR playthrough.

A Polish YouTuber Remigiusz “Rock” Maciaszek was scanned and had a cameo in the game (https://www.youtube.com/user/RockAlone2k)

So I’d like to propose a bold experiment, which I may also try one day. Let’s design a game having YouTube and Twitch in mind from the very beginning. If this way of promotion is indeed so powerful, trying to adapt may be a good idea. So let’s create a game that gives the YouTubers and streamers something worthy of SHOWING, but also has something for the rest, worthy of PLAYING.

----

When working on TWoM I knew it’s a special game, but ultimately the reception is beyond my expectations, and probably a surprise to everyone in the company. I’m glad I could contribute, but it also worked the other way – the influence of the project and the great team I’ve been part of will stay with me for a long time.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like