Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

James Earl Cox III, a student in USC's Interactive Media & Games division, set an ambitious goal for himself: over the next five years, he would develop one hundred games.

"If I don't create something before I try to sleep, I'll be laying there in the dark, trapped by ideas."

After completing the game Landers back in June of 2012, developer James Earl Cox III set an ambitious goal for himself: over the next five years, he would develop one hundred games.

Cox, a student in USC's Interactive Media & Games division, has now completed 77 games, which means he's well on the way to meeting his goal on time.

Running a gamut of play styles, genres, stories, and themes, Cox explores many varied territories with his games. Still, why so many in such a short time? For Cox, it involves a powerful need to create, a desire to grow his skills as a developer, and a constant search for the answer as to what games and play can mean for people.

"I first started sweating out digital games in 2012 and wound up releasing 11 that year alone." says Cox.

This kind of output in a period where many developers might not even complete a single game can seem extreme, but in an era of experimentation and game jams, it's not impossible. Even so, it's quite a sustained effort, one Cox keeps up with to hone his skills as a developer.

"With so many indies floundering every year on their first release, I wanted to ensure that I had a unique design voice and strong practice before going full time."

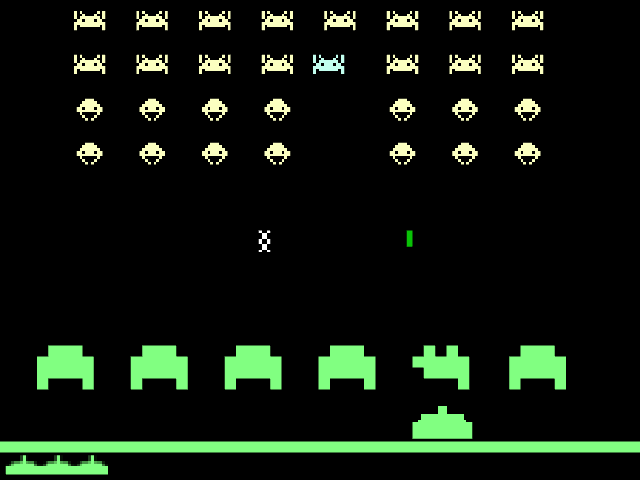

Cox's Landers, a "a Space Invader-inspired and themed critical game"

Cox saw many indies, even ones with strong, quality games, failing to capture an audience. For various reasons, good games are slipping through the cracks. A developer needs to take any opportunity to get a leg up these days, and partly because of that, Cox felt a need to fill out his portfolio before making an attempting to make his way in games full time.

"Making 100 games in five years was a sort of self-ransom; one of the better ideas that young me had." says Cox. Game development skills come from experience. Many developers find success after a few creations, building their abilities up with each successive game. As Cox wanted to build up that experience, what better way was there to do that than to force himself to make one hundred games in a five year span?

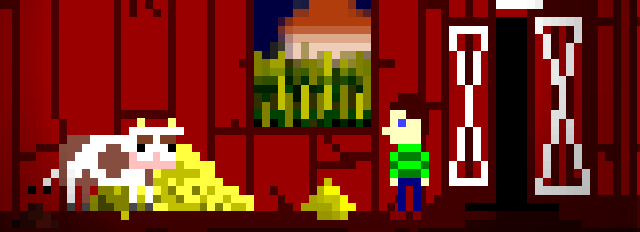

Don't Kill the Cow

Based purely on the numbers alone, Cox would build up a great deal of experience working on different genres, finding his voice, and creating play styles. He'd have a great deal of work to show for his time, and learn all manner of skills along the way.

"Before digital games, I wrote. If not games, I'd find some other outlet; I have to create." Cox enjoys the act of making things, and games offer him a blank slate to paint on in various ways. Giving in to this desire would help him build up the experience he wanted, but also give him an outlet for the ideas that were always floating through his head.

"Too many ideas are always floating around. I try to write them down before they disappear."

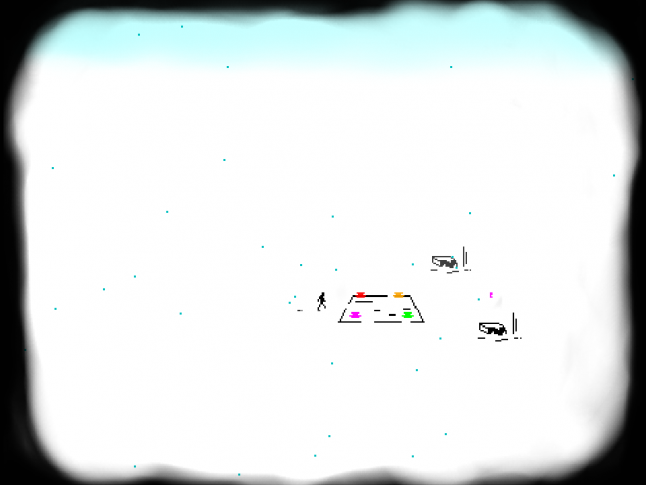

Nivearum

Cox maintains his creative flow through managing several projects all at once, letting them float through his mind and grab his attention as needed. "Some games take time to mature; the overall idea is solid but they need something more," he says. "I juggle two or three of those projects to keep them from going stale."

In other instances, an idea grabs hold of him and refuses to let go. "At times, the game falls into place instantly, and I become engulfed in a fever dream of development," says Cox. "Bottle Rockets' mechanic and story struck hard, and I couldn't escape until I coded it. The four days it took to make Bottle Rockets were spent working until I fell asleep and then getting back to it when I woke. The game's featured song was the only thing I listened to: Aphex Twin's Alberto Balsam on repeat for all four days. Nothing feels as good as releasing a passion game."

Cox is only building up steam with each release, getting faster and sharper with the skills he's gained from almost five years of fever-pitch design. "Depends on the game, but generally I'm spending less cumulative hours on each subsequent game. Development time for An Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge (my ninth game) took about three months back in 2012. Yet, in 2014, Bottle Rockets, EnviroGolf, and Temporality each took roughly four days to make," says Cox.

These aren't just junk projects he's slapping together, either. Cox is producing some quality work with his intense development regiment. "Temporality was on display in National Arts Center Tokyo alongside Ok Go's I Won't Let You Down music video, both Jury Selects. EnviroGolf made it into EGX's Leftfield Collection," says Cox. With each release, he is growing his skills as a developer, creating intriguing works.

With his self-imposed goal, Cox set out to improve himself as a developer and give himself the creative outlet he needed. Still, this was the equivalent of hurling himself into a marathon, one that would last for years. Even the most creative person would have some difficulty constantly coming up with new projects, wouldn't they? Even if they didn't, how would they choose what to work on? What ideas would work, and which wouldn't?

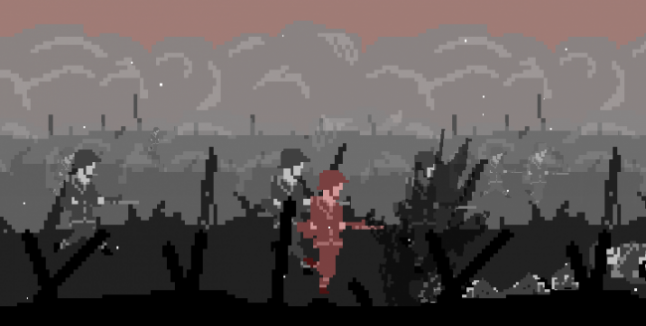

Temporality

Temporality

"Two things have to fall into place for me to feasibly make a game: I have to have the technical ability to make it, and it has to emotionally grip me," says Cox. "If I can't forget the game, if it haunts me, there's a good chance I'll drop what I'm doing and make it."

Cox wants to touch upon something deep inside the player when he creates something. That can involve handling deeper meanings, finding that mixture of fear and arousal that comes from looking up adult imagery for the first time in You Must Be 18 Or Older To Enter. It can also mean playing off of something silly, like a fish racing game.

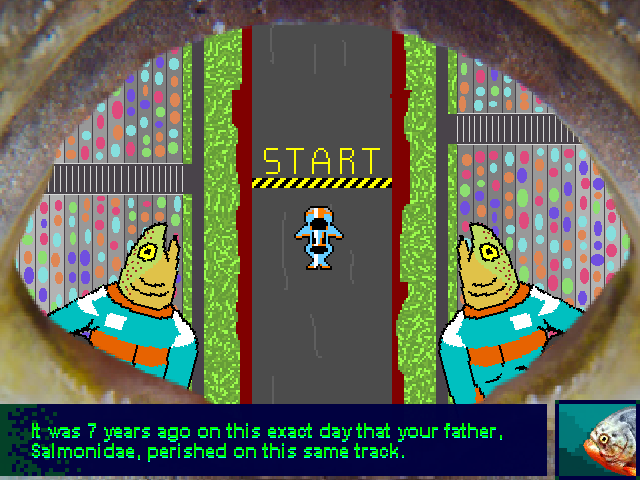

Yet, even in that silliness of games like You Don't Know The Half Of It: Fins Of The Father, there is a powerful emotional core. Players may be laughing at the concept, but within that fish racing game, there is a narrative of a child going through the race that ended his father's life seven years before. There is a story of legacies being passed on that is touching despite the lighthearted nature of the game itself.

This is the interesting core of games - something designed around play and leisure can touch players on an emotional level. Something that is, arguably designed to entertain, can also help us look deeper into our humanity and emotional fragility.

Fins of the Father

When asked what else interests him in a concept, Cox replies, "Subverting player expectations; why do we have to move right? Do we really need collectibles?" Players have come to expect certain things about games, but to Cox, this is a form of stagnation. Doing something because it has always been done that way is not a valid reason when creating.

This means that Cox tries to ask himself why games do things in certain ways, and how he can do something other than what would be expected. In doing so, he can create something truly new that will shake the player up and make them look at games differently.

This does not just extend to mechanics, but rather what can be construed as a "game" at all. What goes into the creation of something to play with? What is it about an interactive experience that makes it into a game? When does something we can manipulate become a game and not just a physical interaction? Cox's works attempt to dive deeper into this question, seeking an answer to the origin of play and games within our minds.

"When I was little, I would smash the buttons on arcade machines during the 'Insert Coin' preview screen, believing I was playing the game. You'll see kids do it today too," says Cox. "But are those kids playing a game? They think they are. I want to make that experience for adults. How much interaction can you remove while retaining the 'game' part of the game?"

What is it that clicks in the mind when we play a game? When is the point when our mind switches over from tedious task and assigns fun to it? Games are just a mixture of button inputs, but through a mixture of visual feedback, sound, and perceived motion, players feel that they are enjoying themselves. Something about the connection between these things, at their core, is what turns our actions into a game. For Cox, it is not just about subverting gameplay expectations to create a unique experience, but it is also a means to discover where play originates.

Simplicity has become important to Cox, as it gives clarity to what a game aspires to do. "Keep the design simple," he says. "Cut out any features that aren't core to the game's message. They're just bogging down the experience. A small game with a unique mechanic beats a long game bloated with bland ones."

Something as simple as when to work can be important for a new developer to know as well. "I work best untethered. Just a short while ago, I tried regimenting myself with a standard wake/sleep cycle. It was an unproductive disaster," says Cox.

In finding what doesn't work for him, he's also seen how to work around those limitations. Sometimes, the answer can be as simple as looking for outside help to bolster the strengths he lacks. "My brother Joe, he and I work amazingly together. Several of my games were co-designed with him (including EnviroGolf), and we often collaborate on the art together. I can't make music to save my life, and that's a skill he's nailed."

Cox's need to create has helped him explore many ideas on what play means, how to subvert player expectations, and build experience as a developer. It's helped him explore aspects of how he works best at design, and what things work well for him. Despite the gargantuan task always looming overhead, Cox continues to look at it with excitement.

"This 100-Games-in-Five-Years will end just as I graduate from USC's Interactive Media and Game Design master's program," he says. "It's nerve-wracking at times; I have to make 23 more games. Crap, that's a lot. God do I love it."

You May Also Like