Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

'Iwata was a so-called otaku,' recalls Yash Terakura, who mentored Satoru Iwata when he was a college kid eager to learn more about computers. 'Of course, we did not have that term at that time.'

The late Satoru Iwata is well-remembered for his role as the president and CEO of Nintendo. But not many know the details of his early years in game design, when he exercised his prodigious programming skills.

And while he did not become an official Nintendo employee until 2000, his relationship with the company dates back to 1983 – a year when Nintendo desperately needed programmers who could harness the technology of their new Famicom system, which would be known overseas as the NES.

This article features an interview with one of Iwata's early mentors, who would go on to be a colleague at HAL America, the North American publishing subsidiary of HAL Laboratories. It also attempts to nail down the details of the first Nintendo games that Iwata ever worked on, one of which would reportedly turn out to be an adaptation of a hit American arcade game.

“I have known Iwata for over 30 years," Yash Terakura recalls in an email. "Iwata was one of many college and high school students who used to flock my office to gather new information on Commodore computers. I think he was a sophomore or junior in university at the time.”

"Iwata was a so-called 'otaku.' Of course, we did not have that term at that time. I would say that he and other students were Commodore groupies."

Terakura would go on to be a colleague of Iwata's at game developer HAL Laboratory, where he would establish an American subsidiary called HAL America and serve as president of the publishing operation that brought HAL games to the NES, SNES and Game Boy. But when they first met, Iwata was a college kid eager to learn more about computers.

Terakura was the manager of engineering for Commodore Computers at the time, working on the development of the Vic-20. "Iwata used to come to my office to help me when I was in Commodore’s Tokyo office," says Terakura.

Terakura remembers Iwata as curious and devoted assistant. “In 1979 or 1980, Iwata was stopping by my office almost every day after school," he writes. "He helped me make test programs, sorted my books and floppy disks, and did other minor things. He was helping so that he could obtain news about our new products, as well as technical information not available to the public."

Satoru Iwata with former Commodore Computer engineer and HAL America president Yash Terakura [right] in November 2002 [Image courtesy of Terakura]

"He was a so-called 'otaku.' Of course, we did not have that term 'otaku' at that time," says Terakura. "He and other students were Commodore groupies.”

Iwata enrolled in the Tokyo Institute of Technology and majored in computer science in April 1978 at the age of 18. [Read more background here.] During his sophomore year, he began working part-time for game developer HAL Laboratory, which was officially established in February of 1980.

"It was my good luck that the Famicom system's CPU was the 6502. The CPU was unknown to all but those who had a special liking for it."

“Iwata was a software engineer, but he wanted to learn more about hardware," recalls Terakura. "I did teach him some hardware engineering."

Nintendo was doing some hardware engineering of its own in 1981. According to an “Iwata Asks” feature, Masayuki Uemura, head of Nintendo’s Research & Development Department 2, was put in charge of working on a system to play video games on home television sets. This was just one year after the release of the Game & Watch, and four months after the release of the Donkey Kong arcade game.

Uemura would work with semiconductor manufacturer Ricoh on developing the CPU of what would eventually be the Famicom. The engineers at Ricoh suggested a 6502.7 CPU, a modified version of the 6502 CPU. [Read more about the development of the Famicom here.]

The 6502 core CPU (RP2A03) on a NES (Nintendo Entertainment System) NTSC board, manufactured by Ricoh, is bordered in red

“It was a CPU unknown to all but those who had a special liking for it,” Iwata has said. “It was my good luck that the Famicom system's CPU was the 6502. By chance, the computer I used for fun in university was a Commodore PET. Its CPU was a 6502, so by the time I started working, I was a 6502 expert."

“Iwata knew a lot about 6502 machine language, the programming side,” says Yash Terakura. "I taught him about the hardware aspect of the 6502."

Iwata would join HAL Laboratory full-time in April 1982 after graduating from the Tokyo Institute of Technology, bringing his knowledge of the 6502 with him.

Nintendo and Atari were close to signing a deal in 1983 that would have given Atari worldwide rights to sell the Famicom system outside Japan [as chronicled in the book Game Over by David Sheff.] Nintendo would provide the Famicom hardware and develop software, while Atari would market, sell, and distribute all of it outside Japan. Satoru Iwata would develop software for this Nintendo-Atari deal.

In his second year at HAL Laboratory, Iwata had heard about Nintendo’s plans to introduce its 8-bit Famicom console to Japanese retailers. He had the confidence to approach Nintendo directly in 1983 seeking an opportunity to develop games and program for the console.

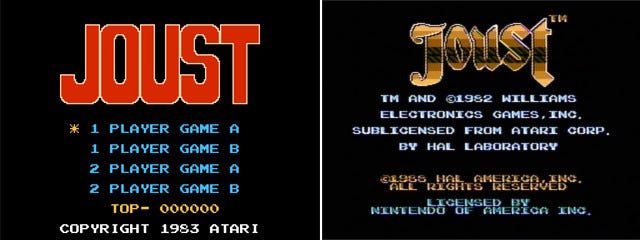

The first Nintendo Famicom game that Iwata would produce was not a Nintendo property, but an arcade game Atari had licensed from Williams Electronics: Joust. At that time, Atari had already acquired a license for Joust from Williams Electronics, releasing it for the Atari 2600, 5200, and even the Apple II and PC under its Atarisoft label.

According to an Atari inter-office memo with terms of the deal disclosed dated June 14th, 1983 (One month before the Famicom would be released in Japan), Atari could order Nintendo to program four Atari games of their choice for their own Famicom release:

Nintendo will, in the interests of expediency for this Christmas season, program 4 Atari titles of our choice. Source and object code which meets our satisfaction (with respect to basic design, tuning, and bug-free) to be delivered to us no later than Sept. 1, 1983. The fee would be $100,000 / title or no non-recurring engineering fees would be charged as long as we buy a minimum of 100,000 cartridges.

Iwata confirmed his work on the game in an interview with a now-defunct Japanese magazine called Used Games. “I went to Nintendo and asked if I could make a Famicom game, then produced Joust over about 2 months,” he told the enthusiast magazine in 1999.

"Programmer Satoshi Iwata Who Supported The Nintendo Game", an article in Used Games magazine, Autumn 1999. (Via @GAMESIDE.)

When presented with a copy of the magazine article, a spokesperson for HAL Laboratories confirmed a brief translation of Iwata’s statement that he indeed programmed Joust for the Nintendo Famicom. The spokesperson did not have any further information on Iwata’s work on the game (or any supposed role HAL staff may have had) citing the amount of time that has passed.

The deal to have Atari distribute the Famicom outside Japan and publish the Atari games that Nintendo programmed never happened. (Sources differ on the reason it fell through.) Had the deal been signed, the fates of both Nintendo and Iwata would have been radically altered.

As for Joust, in the same 1999 magazine interview Iwata said: “Due to various reasons, the game wasn't released by Nintendo.”

Two other games appear to have been completed in 1983 for the Atari Nintendo deal. In addition to Joust, Atari had also licensed Stargate (also known as Defender II) from Williams for its Atarisoft label. Atari appears to have held the worldwide home console and computer rights for both games at that time. The other title appears to have been Atari’s Millipede. The production staff that worked with Iwata on these games in 1983 (either from Nintendo or HAL), and the other Atari games planned for the deal currently remains unknown.

But the games would eventually see the light of day. HAL would later release them in Japan and America with the help of Yash Terakura, Iwata’s former mentor from Commodore Japan. Both men came together again to form a new working relationship where Iwata and HAL staff would produce games in Japan, and Terakura would market and sell them in North America.

On the left is the Famicom title screen of Joust, published by HAL Laboratory in 1987, which displays a 1983 Atari copyright year. On the right is the HAL America version of Joust published one year later, which removes the 1983 Atari copyright year.

On July 15th, 1983, Nintendo would release the Famicom with the 6502.7 Ricoh CPU to the Japanese retail market. No game developer other than Nintendo would release Famicom games for a full year. Software engineers from other game developers needed time to learn how the Famicom’s Ricoh 6502.7 CPU generated graphics and sound.

The first years after launch were tumultuous for Nintendo. In addition to having their planned deal with Atari Inc. go nowhere, the company was dealing with an array of growing pains which included a recall due to defective hardware. It was not until early 1986 that Nintendo would have a licensee program in place. (Iwata and his Nintendo colleagues would discuss this challenging period in an Iwata Asks feature.)

The Famicom needed quality game software, and programmers that knew the 6502 CPU. Even though Nintendo rejected Joust, they realized that talent was in short supply and they couldn’t develop games solely on their own. Nintendo was impressed enough to have Iwata and HAL program games for the Famicom.

Iwata would go on to show Nintendo R&D staff how to utilize the 6502. In an “Iwata Asks” feature, Iwata recalls pointing out a technique to save memory to Nintendo’s R&D 2 chief Uemura: “I showed you something and was like, ‘Look what you you can do with the 6502’, there's this bug you can make use of,” says a chuckling Iwata.

Iwata and HAL would be kept busy in 1983 and 1984 on Famicom titles that included Pinball, Golf, F1 Race, Balloon Fight, and Mach Rider. Nintendo would design the games, and HAL and Iwata would program them.

Many have noted that the central flight mechanic in Balloon Fight is similar to the one in Joust, which Iwata also worked on. In 2013, Iwata showed off Balloon Fight to long-suffering Chief Arino on an episode of the Japanese TV show GameCenter CX. The CEO of Nintendo spoke fondly of the game he had worked on "back in his programmer days."

Terakura was there to see Iwata climb the corporate ladder at HAL. “Since he was the manager of engineering at HAL Japan, he was somewhat involved with everything,” remembers Terakura. "He came to US office few times, and I went to the Japan office every so often.”

Iwata was no longer the eager young devotee who had gladly helped out around the Commodore office. “He was a very quiet person, and he was nice to others," Terakura recalls. "But when it came to a design or concept of a project, he could be very hard headed. He did not agree with other people unless he was very sure that their idea was better than his."

Terakura left HAL around the time that it was forced to declare bankruptcy, and saw Iwata less frequently thereafter. "I started my own company, but we kept in touch," he says. “I go to Japan often, so I was planning to call him and have a dinner in August or so. I guess that will never happen."

****

John Andersen is a journalist, product consultant, and video game historian.

You May Also Like