Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Themes, allusions, and symbols are plentiful in TUS, emphasizing the natural wonderment felt by the player and bolstering the experience with rich content. I've chosen to break up my writings into chapters to parallel the game's structure/narrative.

[This post originally appeared on PSNStores.com]

Chapter Four- Realization

Helpless

Chapter four begins with the player listening to the King as he recounts his life story. A hippo urges the player to “come, sit by the fire,” a surreal anthropomorphic instance that elicits a puzzling response. A close look around the room reveals that the King is surrounded by pictures of himself and his accomplishments. Some of the pictures, like the statue in the upper-left corner, capture where the player has previously ambled. Others seem like commissioned selfies of a narcissistic monarch. It’s telling that the man is sitting by his lonesome, considering he surrounded himself with himself throughout his life (contrary to advice from Yes). He built his island and now has to live on it. The blank pictures on the mantle are what interest me most. Perhaps they represent the son he never knew, or regret for unfulfilled accomplishments. In any case, the King is about to tell you the details of his dream. To know the King, we must first be the King. The player is transported into a picture that depicts the house the King grew up in. Exploring a bit, the curious player will realize that there’s a mirror on the wall. Jumping on a nearby table allows the player to realize that she is now playing as the King, albeit a younger version with shorts and an underrealized moustache. I’ll get more into this in a minute. Due to the King’s narration moving the player along, it’s easy to miss this first mirror. In pushing through a door, a familiar site comes into view. The space is completely white, much like the opening sequence in the game. By now, this trick isn’t quite as impactful, but it is soon explained that by painting to find your way, you have ruined the King’s garden. The common response here is recognition that you, as Monroe, negatively affected your father’s dream. You ruined everything, a potential nod to growing up and creating your own path as opposed to following in the footsteps of the one that came before you.

Fourth Wall

The game breaks the fourth wall when credits start showing up. The King mentions that his dream has credits and subtitles, too. Like the rest of the game, this is done with creative spirit. The first credit the player comes across proclaims that The Unfinished Swan is “a dream by Giant Sparrow.” Notice the omission of the word game. As I mentioned in the intro, I consider TUS to be more of a game than Journey; one that successfully weaves a compelling narrative by allowing the player to explore its world. I won’t get into juicy, controversial details, but what it comes down to is that throughout TUS, the player feels almost completely immersed. The only aspect of the game that causes a hiccup in said immersion is the lose condition; the false death that places the player a few steps back from where he met his demise. Thankfully - and, I submit, purposefully - death doesn’t come too often throughout the game. My entire playing of Journey was haunted by the fact that I knew I was playing a game. It may be worth a replay, but my honest feeling after completing Journey was relief that I was done playing it. I can’t say the same for The Unfinished Swan. On with the dream. Peering over a ledge, the unfinished labyrinth comes into view. Words like ‘abandoned’ and ‘forgotten’ are used, highlighting the King’s remorse. An interesting effect is the fact that as the King is narrating, he’s speaking in the first person, the very same view that the player is donning. You are playing in a memory, a dream, and it actually feels like that due to the narration. In addition, MC Escher-esque architecture starts jutting out everywhere, challenging the player’s perception of up. About the vines that took over his kingdom, the King poignantly claims, “I built it to stand a hundred lifetimes. Instead it’ll be buried in one! A monument for weeds.” Everything crumbles and the dust returns to the earth by the earth. How long a legacy lasts varies, but none lasts forever.

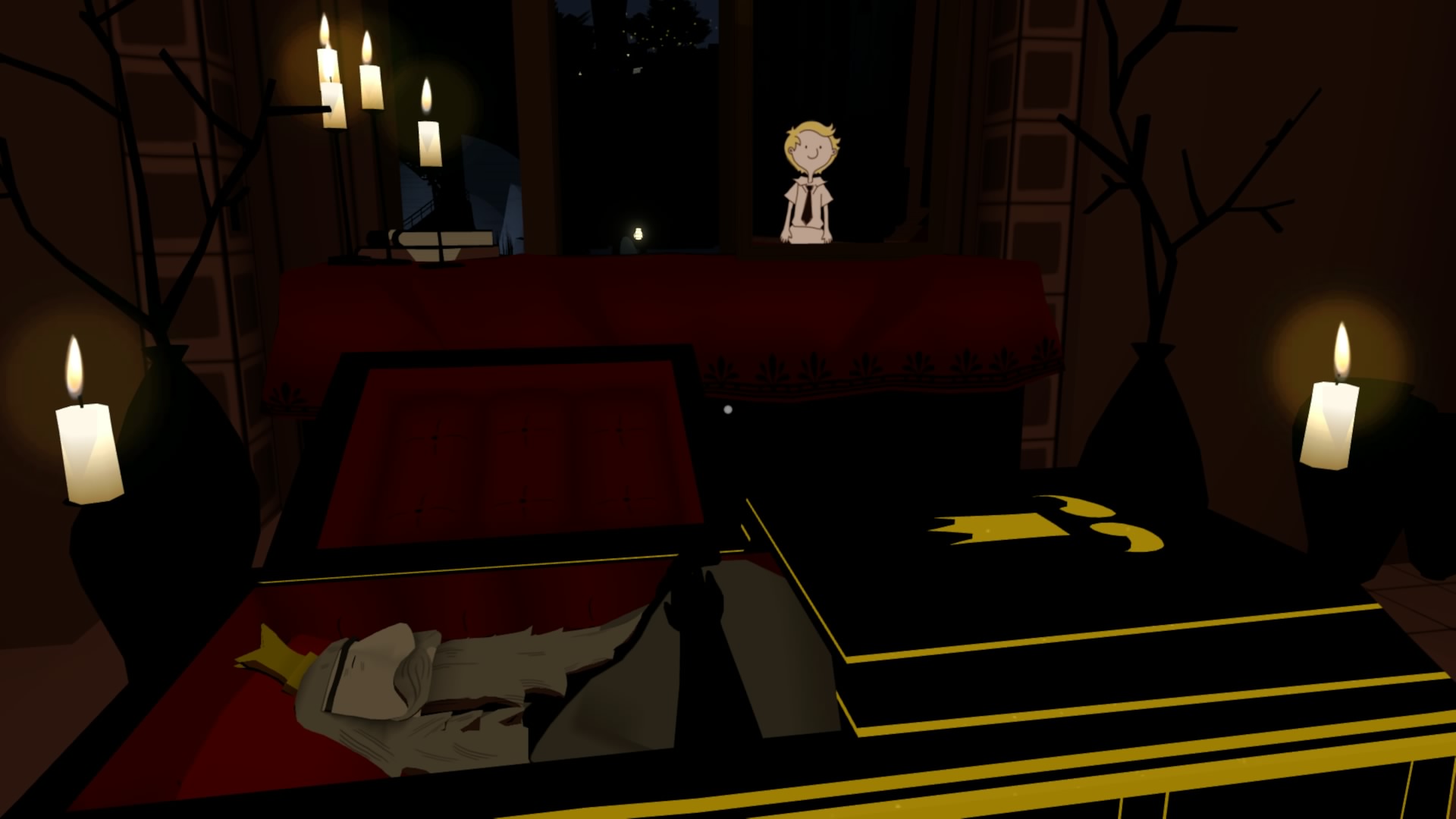

A Lonely Viewing

Moving forward, the player reaches a dark portion of the dream as the King waxes poetic about finite legacies. Soon, the player walks into the King’s funeral. Nobody is in attendance “except you.” At this point, the player swaps back to controlling Monroe, which is confirmed by looking into the mirror on the coffin. I was initially shocked to find that the character models are so basic. Monroe looks like a cardboard cutout, shoeless and gesture-less. With some thought, I came to the conclusion that this is the same feeling human beings have in their infancy. The player is practically forced to move left and right, jump up and down to realize that the image in the mirror is the character she is controlling. This realization of self is a very human trait, one that is learned early on. Educational psychologists Teresa M. McDevitt and Jeanne Ellis Ormrod describe it thus:

In the second year, infants begin to recognize themselves in the mirror. In a clever study of self-recognition, babies 9 to 24 months were placed in front of a mirror (M. Lewis & Brooks-Gunn, 1979). Their mothers then wiped their faces, leavning a red mark on their noses. Older infants… touched their noses when they saw their reflections, as if they understood that the reflected images belonged to them. (450)

What seems like the use of cheap assets is actually a clever trick by Giant Sparrow. Walking through the open window, the player grows larger and larger (“like a teenager”, the King proclaims), pushing over the giant monument. His final hope at leaving a legacy is now toppled, and the King comes to terms with the fact that when he’s gone, he will be painted over “the same way I painted over what was here before me.” At this point, his tone has evolved into a gentle acceptance of his fate. When he reflects in solitude on all the things he’d built and left unfinished, he recognizes that he had fun making them. The journey is the important part, not the end result. I try to imbue this idea in my students, the fact that the end of a work does not define its whole. It’s something that we grow up thinking, that if the end is not to our liking - not twisty enough, not happy enough, not resolved enough - then the whole work is the worse for it. I reevaluated this idea the first few times I watched Signs, the M. Night Shyamalan film that is lambasted for its sterile ending. The movie hits all of the right chords up to the realization that the aliens are allergic to water, or something along those lines. Even if the idea of aquaphobic aliens invading a water-based planet is silly (it sort of is, I’ll admit), does that discount the rest of the movie? Cinematically, it’s very well shot. The acting is top notch regardless of your personal feelings for Mel Gibson’s off-screen performances. The suspenseful scenes, the jump-scares, the narrative of a man who has lost his faith and is struggling with ideas of coincidence vs. divine intervention - those are shining portions of the movie, and should not be tarnished by an unfulfilling twist. As cliché as it sounds, life is the same way. It’s not the end but the means that define the journey. We’ve all got the same ending coming up, but how we get there varies from person to person. I’m reminded of Prince’s “Let’s Go Crazy,” when he philosophizes:

We’re all excited/

But we don’t know why /

Maybe it’s ‘cause /

We’re all gonna die/

And when we do/

What’s it all for?/

You better live now/

Before the grim reaper come knocking on your door.(36-43)

A similar sentiment was held by carpe diem poets. In “To His Coy Mistress,” a poem wherein the speaker attempts to win the affection of a lady, Andrew Marvell writes, “But at my back I always hear / Time’s wingèd chariot hurrying near” (21-22). His main argument is that coyness will lead to a joyless (sex-less, in this case) life, which will end unceremoniously in death. But back to the conclusion of The Unfinished Swan.

Passing the Torch

“I have something for you,” remarks the King. “This brush isn’t mine anymore. My work is over. It belongs to you now.” The King figuratively passes the torch to his son. When he adds “I hope it makes you happy, and that someday they will say he is a better man than his father”, I admit I choke up a bit. I don’t have any personal issues of living up to my father’s legacy or being a better man than him, but I think Giant Sparrow has chosen a feeling that strikes a chord with a wide audience. I don’t have children yet, but there’s an innate feeling that I already possess of wanting them to have a better life than I’ve had. Psychologically speaking, I honestly don’t know if this is a universal human trait. I do know that when the camera pans toward an open door and the player is forced toward it, the deeper meaning is that life is a blank canvas waiting to be painted. ”None of this will last for long”, the King prompts, an attitude echoed by artists throughout human history. The game ends with an image of Monroe sleeping in his bed after finishing his mother’s painting. In addition to filling in the swan’s neck, he paints a couple of Cygnets (don’t feel dumb, I had to look it up, too). In general, this could symbolize having and raising offspring. In the context of this story, I imagine the big swan represents the King while the smaller two, who were created by the bigger, represent Monroe and his mother. The storybook conclusionary “The End” sends the player off with a warm and fuzzy feeling. The book closes, and from here on out, the player sees the back cover on the title screen.

The Finished Swan

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like