Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Can asynchronicity work for more than simple board games? Indie developer Derek Bruneau describes the process of building asynchronous gameplay to RPG Conclave, examining the history of the form and how it works for him.

October 18, 2012

Author: by Derek Bruneau

Can asynchronicity work for more than simple board games? Indie developer Derek Bruneau describes the process of building asynchronous gameplay to RPG Conclave, examining the history of the form and how it works for him.

How much time do you have to play games? For many of us, the answer is, "Not enough." Finding time is often even more difficult when it comes to multiplayer games: not only does each player need to have free time, but their schedules need to align. Multiplayer games that expect physical proximity -- board games, Johann Sebastian Joust -- present an additional hurdle.

Some multiplayer games mitigate these difficulties by offering asynchronous play. Not everyone agrees on the definition of "asynchronous"; here I'm using the term to refer to multiplayer games where the game state is shared but players' participation isn't simultaneous. Words With Friends is a recent example of a game that's asynchronous by this definition: the board is shared, but players take turns separated by arbitrarily long periods of time.

Though a synchronous (simultaneous) game might inspire an asynchronous version, it's unusual for a single game to allow players to switch between both modes of play on demand. For some, this just isn't possible; it's pretty difficult to imagine a version of Johann Sebastian Joust that isn't played simultaneously. But couldn't other games support both styles?

That's what we set out to do in our game Conclave. We took a genre that's usually played synchronously -- the online co-op roleplaying game -- and developed a game that allows players to shift to asynchronous play when desired. In this we were guided by the long history of asynchronous adaptations of synchronous games, but that didn't prevent us from running into challenges along the way.

Though less common historically than synchronous play, asynchronous play is not new. Correspondence chess, with moves exchanged by courier or postal carrier, has existed for centuries, if not longer.

More recently, players and game creators extended the play-by-mail (PBM) approach to games involving more than a simple exchange of moves. Only a few years after the board game Diplomacy was published in 1959, groups of players were negotiating (and breaking) alliances and submitting orders through the mail rather than over the board. Even though a game might involve up to seven players, Diplomacy lends itself fairly well to asynchronous play: negotiation is open-ended and best conducted privately, and players' actions are resolved simultaneously, making the order in which they submit them unimportant.

Other PBM games like It's a Crime -- think Mafia Wars, but with more direct player interaction and a lot more firebombing -- can accommodate dozens of players. In practice, however, you typically interact with only a small subset of other players at any time, which keeps the scope of play to something manageable.

New technologies have provided additional ways to play games asynchronously. Email and online forums have led to play-by-email (PBEM) and play-by-post (PBP) games, respectively. PBP is a particularly popular alternative for pen & paper roleplaying games like Dungeons & Dragons, and our experiences with it influenced some of the design decisions we made for Conclave. (More on those below.)

While PBM, PBEM, and PBP games emerged mainly as a way to eliminate the requirement of physical proximity, other asynchronous games have become popular even with players who share a living space. Mobile apps like Words With Friends, Scramble With Friends, and Draw Something are played not just by distant friends but by roommates, significant others, and spouses. Here, asynchronicity provides opportunities to reinforce our social connections in moments scattered throughout the day or week, rather than requiring us to coordinate schedules.

Though many of the previous examples are asynchronous adaptations of synchronous games, few allow you to switch between the two modes of play. Unlike its synchronous, physical inspiration Boggle, the Scramble With Friends app doesn't allow players to find words simultaneously, even though both are shown the same set of letters.

This opens up some design space -- the app offers power-ups that affect only a single player's view of the board -- but closes off other possibilities. In Boggle, you can tell how many words another player is writing down, which heightens the tension of the game; Scramble can only imperfectly capture that feeling of head-to-head competition, even if players are in the same room together.

Conclave is a browser-based co-op RPG with story, mechanics, and aesthetics inspired by tabletop games. Parties of up to four players work together to complete quests that are a mix of tactical combats and group decisions driven by the story and the skills of the players' characters. Like most multiplayer online RPGs, it offers synchronous play, but it also supports asynchronous play and lets players switch back and forth between the two. Here's how we made that possible.

Conclave (Click for large version)

1. Turn-based, but not ordered

At the outset, our desire to support asynchronicity led to a fundamental decision: that Conclave's combat would be turn-based.

We could have picked a different organizing principle -- perhaps a Diplomacy-influenced scheme where players choose their actions independently and the game then resolves them in a batch all at once -- but turns are familiar to both tabletop and computer RPG players and provide a convenient way to divide combat into chunks that can be played at different times.

In addition, each chunk is small enough that it doesn't require a major time investment, making it possible to take a turn whenever you have a few minutes to spare.

Initially the game assigned a turn order to players. In a particular round of combat, Amy might need to take her turn first, followed by Ben, then Chris, and finally Diana. While turn order is a tradition in tabletop RPGs -- not to mention most turn-based games -- it quickly became apparent that it could lead to frustration when playing Conclave asynchronously.

Chris might have a free moment and be eager to take his turn, but if Amy or Ben hasn't taken a turn yet, he can't play. In a two-player asynchronous game, you only have to wait for the other player, but with three or four players the waiting is magnified.

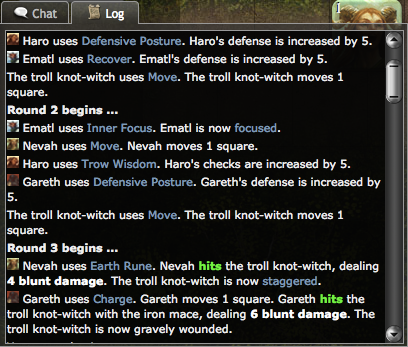

A close-up of the party log showing players acting in different orders each round.

To address this issue we simply removed the concept of turn order from the game. Players can still take only one turn per round, but they can take them in whichever order they prefer. Besides reducing the amount of time players spend waiting, this change has a couple of other benefits:

A player that acts last in one round has the option to immediately take the first action in the next round, further streamlining play.

In a tight spot, players can act in whichever order gives them the greatest tactical benefit. With a turn order, you're sometimes forced to act suboptimally: an ally might have an ability that can make a foe more vulnerable to your attack, but that's not immediately helpful if you're required to act first. With no turn order, you can ask your ally to use the ability and then follow up with your (now more effective) attack.

Of course the change was not without trade-offs. Games with turn orders sometimes introduce special abilities that allow you to take your turn earlier than normal; that's a bit of design space Conclave can't explore. In addition, the lack of turn order has an implication for synchronous play: two players might submit their turns at nearly the same time, rendering the later player's action suboptimal or invalid. As a result, we've had to do extra work to handle these conflicts, and in the future we plan to avoid more of them by showing players when someone else is in the process of taking a turn.

Even so, the benefits of streamlined play and additional tactical options are worth it.

2. Saving the timeline

Another complication introduced by asynchronous play is keeping track of what each player has seen. In a game where two players alternate turns, this is straightforward; the game can always display its current state to both players, and neither one will miss anything. That's not true once more than two players are involved and playing asynchronously.

A close-up of the event/timeline navigation controls.

Building on the example above, suppose that Amy takes a turn and then logs off. If Ben and Diana take turns before Amy logs back in, it's not enough to show her the current state of the game; the results of Ben's turn will be obscured or eclipsed by Diana's. In Conclave, the party's enemies also take turns during combat, which means that a dozen or more combatants might act between your own turns. That's a lot of intervening action to puzzle out from "before" and "after" views of the game.

As a result, we've elected to save every action in the game as a kind of timeline and track where each player is along it. If there's a lot of activity on your quest while you're away, when you come back you'll see the first action you missed; you can then navigate forward in time to see the remaining turns play out in sequence. In effect, you see the action the same way a party playing synchronously sees it, except that it's not "live".

Saving actions in a timeline has a nice side benefit, too: players can go step back through previous events in the game and review them at any time. You can review past combats for tactical inspiration if you encounter a troublesome foe, and you can also review the decisions you've made along the way for hints of what to do next in the story. All of this is possible whether you're playing synchronously or asynchronously.

3. Device agnosticism

Because Conclave doesn't place any restrictions on when or how you play, new activity in the game can occur at any time. That presents an additional challenge if we want asynchronous play to be convenient: you need to have a device that can access the game whenever you want (and are able) to play. Furthermore, you might prefer to use a different device -- smartphone, tablet, laptop, desktop -- at different times. Mobile devices offer portability so that you can play on the go, but for some games it's hard to pass up a larger screen when one is available.

As a tiny development team, we doubted that developing native versions of the game for a variety of platforms would be the best use of our limited resources. Since we planned to regularly add to and improve the game, we wanted to minimize the amount of work required to deploy changes to all players.

Consequently, we chose to implement Conclave's client with HTML5 and JavaScript -- to be precise, with the parts of those technologies that are reasonably (and increasingly) well supported by modern browsers. All game data is stored on our servers, making it possible for players to pick up right where they left off regardless of which device they happen to be using at any given time.

Here the trade-off was clear from the beginning. Pretty much any device with a recent web browser is a platform for Conclave, and that includes iPhones and iPads since the game doesn't rely on Flash. On the other hand, the game can't take advantage of all the functionality provided to native apps, and the tools for developing HTML5/JavaScript apps are still evolving, to put it kindly.

Fortunately, Conclave's technological and aesthetic requirements are relatively modest, and the tools for building web apps continue to expand and improve.

4. Maintaining connections between players

Asynchronicity presents a final challenge: making sure players agree upon and share a pace of play. Many play-by-mail and play-by-posts tackle this problem by setting explicit deadlines: a PBM Diplomacy game might require players to submit orders every two weeks or every month, while a PBP D&D game might require players to post at least once a day.

As a starting point, Conclave takes its cue from the latter. By default, all players must submit their turns within 24 hours; if a player doesn't, the game will take defensive action for the turn on his or her character's behalf. The timer can of course be turned off for cases where a player expects to be away for longer than a day, and it doesn't apply if you're playing solo.

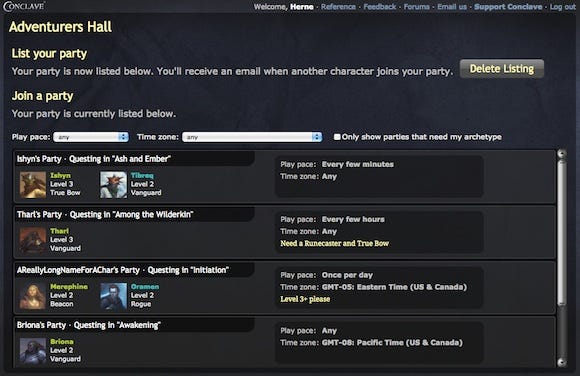

The Adventurer's Hall (Click for large version)

This is a reactive approach to the problem, but Conclave pairs it with a couple of proactive ones. In the game's Adventurers Hall, parties looking to fill out their ranks can advertise their preferred pace and primary time zone. In addition, groups playing asynchronously receive email notifications when significant events occur, such as a new round beginning or a quest ending in failure. Players therefore don't need to continually check the game's status.

Finally, we give each party its own persistent chat room. When playing synchronously, players can use it to communicate in realtime; when playing asynchronously, they can use it to leave messages for each other instead. Here a single user interface satisfies both modes of play, making it easier for players to build camaraderie and share in the experience without thinking about the mode they're in.

Conclave is in open beta, and we're still refining how we handle the shift between asynchronous and synchronous play based on player feedback. In particular, we're looking at other ways for asynchronous players to stay in the loop besides triggered notifications, and we're working to prevent conflicting turns between synchronous players through better UI feedback and design. You can keep an eye on what we're doing at playconclave.com.

Meanwhile, we look forward to seeing more games -- and more genres -- experiment with supporting both synchronous and asynchronous play.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like