Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Creating item interactions in adventure games, especially realistic ones, can be quite a headache, but there is a creative sweet spot most should aim for.

Adventure games, if you really look at them, operate inside of domains that work using their own custom logic. This could be said for practically all games, but adventures have a strong connection with the everyday experiences all of us have - while most of us haven’t (yet) gone to wage war in Earth’s orbit, all of us had to open a bottle when we didn’t have the proper bottle opener. Or we got locked out of our home and for a moment, thought about options that are at our disposal before a loved one or a locksmith arrived. All of these interactions imagined or real, are an integral part of most adventure game experience, regardless if they are made for core gamers, mid-core ones or a casual audience.

In the most basic gameplay sense, aside from the obvious strong narrative aspect, an adventure game is a process of exploration that takes place through solving challenges. These can come either in the form of puzzles, or self-contained mini-games, or something we could label as item interactions - a process of using elements of the player character’s inventory for the purpose of achieving a clear goal. Opening a bottle could be a goal, as well as unlocking a door.

For game designers, especially those who are not focused primarily on the game's narrative, creating these interactions is the bread and butter of their job. Naturally, a big part of this process is predefined by the game setting. It makes a world of difference if a game is set in a high fantasy kingdom where the players act as an elf investigator or if a game takes place in a realistic and contemporary setting.

Setting a game in reality also means having many of its elements feel familiar to the players. The same idea also means that creating interactions become more challenging. As a realistic adventure unravels, players will slowly get sick if every door opens with a key and if the bottles are opened with a series of corkscrews. Here, the job of game designers becomes tough and their creativity usually goes towards two polar opposites - the mundane and the bizarre (this analogy closely follows one proposed by Feng Zhu when it comes to creating concept art).

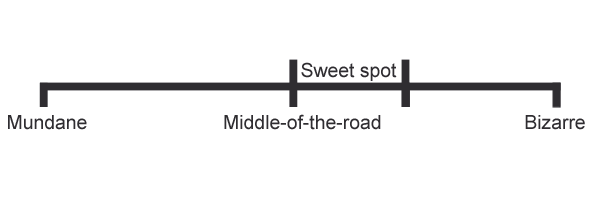

Imagine all possibilities for a particular interaction placed on a single dimension, like a continuum, with two opposite extreme values. On one side, there is the extreme of mundane, while on the other side, sits the bizarre extreme. The mundane option is to go for the most logical and clear item interactions; the purpose here is to allow players to quickly connect items with their possible uses. Bizarre considers options that are everything but mundane where the main objective is to be creative and out-of-the-box with the proposed solutions.

Let’s take the notion of opening a locked door, regularly a hellish problem for adventure game designers. The mundane item interaction would use an adequate key and with it, allow the player character to unlock the door. This is completely logical, but mostly very boring and not really a challenge.

The bizarre option would be to take a huge subwoofer and place it near the door, turn it on and allow it to shake & break it open. This is interesting, but players would have a hard time making this logical connection without previously having it established in some form by the game’s setting (for example, you play a character that is a roadie working for a glam rock band). A middle of the road solution, located between these options is something game designers mostly go with. For example, a lockpick set would be the item of choice here, either full-on or as an improvised set (from tweezers and nail scissors, or something like that).

But, there is a sweet spot when it comes to designing item interactions and it is located not in the very middle, but just a bit towards the bizarre end of the same continuum. Here, two things come into play (pun not intended) - first is the natural suspension of disbelief that all games work with and the second one is the idea of allowing the player to make a discovery which is not super-obvious (which is why the sweet spot does not lean towards the mundane).

In the case of the door, a captive bolt pistol like the one seen in No Country for Old Men is a great option for a realistic game. It’s interesting and plausible, regardless of the fact that probably no one ever opened a door this way (either by blowing away the lock or the hinges). But, like in the film, it sort-of makes sense and the audience does not feel the need to question it. An added bonus is that a bolt pistol, like many other item interactions in the sweet spot, simply looks and feels witty and colorful, without being completely disconnected from the real-world logic.

With this spot in mind, designers can approach their item interaction problems with a more defined method of finding stuff that both makes sense and feels interesting to the players.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like