Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

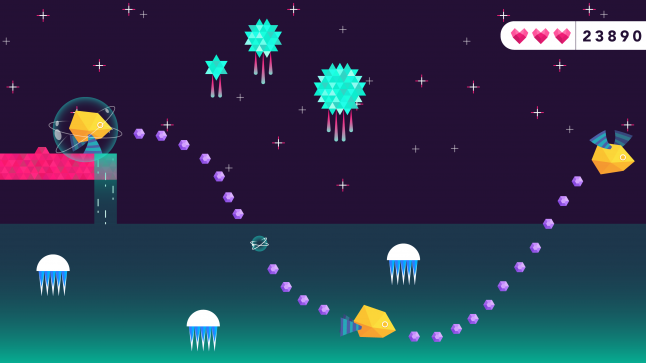

"Ziff is a physical toy that you can build and then play with on screen. By configuring the toy, you define the abilities your character has in the game, helping her adapt to the environment."

The 2016 Game Developer's Conference will feature an exhibition called alt.ctrl.GDC dedicated to games that use alternative control schemes and interactions. Gamasutra will be talking to the developers of each of the games that have been selected for the showcase. You can find all of the interviews here.

A toy takes on a life of its own as a child uses it in their imaginary adventures, much the same as the digital adventures of game heroes. A toy's life is fueled by imagination and touch, creating a tactile manifestation of a child's ability to concoct worlds, personalities, and stories. Like characters in a game, the player uses their toy to create a version of themselves in a made-up world.

That is a connection that Alejandra Molina wished to explore with Ziff, a game that is controlled by a toy with interchangeable parts. In the game, the heroine comes across problems that can only be solved by swapping out parts of the toy, helping her fly, swim, and run as the game requires. In this, the toy brings a physical touch to games, and helps inspire even more creativity from the children who played with it. If the toy could do this much in the game, what other adventures could it go on outside the digital world?

Ziff is slated to appear at GDC's Alt Ctrl GDC exhibit, bringing the inherent creativity of toys and the new connections they can make with games. Alejandra Molina answered some questions about the game for Gamasutra.

Molina: Ziff started as my personal thesis project for my Interaction Design Program at Copenhagen Institute of Interaction Design. So, I chose the topic, did some research, came up with the idea, designed it, built the toy and electronics, and developed the game.

A team started to form along the way. A friend and classmate, Line Birgitte Borgensen, offered to do all the artwork for the game. Another friend, Nicklas Ngyren, made the music. And when I found out I would be showcasing it at GDC, I invited more people to join me. Rodrigo Cabrera and Andrés Molina are now working on the digital game, and Feild Craddock is helping me redesign the toy.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Molina: Ziff is a physical toy that you can build and then play with on screen. By configuring the toy, you define the abilities your character has in the game, helping her adapt to the environment.

Ziff has two legs that, when placed at the bottom allow her to walk, when at the sides let her swim, and when at the top make her fly. She also has a set of core power stones that give her energy and slightly different abilities.

Molina: I don’t really have a background in game design or game development. I’m an Interaction Designer and Engineer. I studied Industrial Design, Robotics Engineering, and worked as a UI designer and Front-End Developer. I have, however, made some very simple games in the past, usually linked to physical interfaces. One example is Tank Notes (http://alemolina.me/project/tank-notes/) which I designed and built with Håvard Lundberg and Andreas Refsgaard.

While working on Ziff I learned about game design mostly by trial and error, but also from Extra Credits on Youtube, and the Copenhagen Game Collective, an amazing group of people interested in independent game culture.

Molina: For the digital side, I only used Unity, mostly because I had decided I wanted to learn to develop in Unity. For the toy, I used RFduino, an Arduino compatible board with bluetooth capabilities. To program the board, I only used the Arduino IDE with RFduino libraries.

Molina: There were two versions of the toy. The first one I handcrafted out of polymer clay, which gave it a very pleasant look, feel and weight.

The second one, though, had to be built really fast, so Feild and I built a 3D model, and we printed it.

Apart from the core of the toy, I used some electronics, of course. The connections are made with magnets, and apart from that, it’s just wires, resistors, buttons, copper tape and the board. All the electronics are encased inside of the toy and are not exposed.

Molina: We spent 8 weeks on this project, and the first 5 weeks I was doing research, deciding what to do, and trying out different alternatives. Once I knew what I wanted to do, I had three weeks left. So I developed the game, built and designed the toy in 3 weeks.

Now that I’ll be showcasing at GDC, I’ve had some more time to improve and make a few changes, although I haven’t been working on it full time, like I was at CIID.

Molina: Well, that was the tough part. That actually took more than half of the time assigned to this project. Initially I just knew I wanted to do a fun project - something that involved a few of my favorite things: gaming, coding, physical computing, illustration and, of course, interaction design. So I decided to work on the connection between physical play and digital gaming.

I tried to identify what digital games had over physical play, and the other way around. From that, I defined my goal: to include the tactile experience and some of the freedom of physical play into digital gaming. I explored a few possibilities. Could you build your own world? Your character? Influence the game with your surroundings? After a few Brainstorming and Co-Creation sessions, I settled on one thing. I wanted a toy that you could build, and it would then be your character in a game.

I found characters interesting, because it was one of the things that my users mentioned many times. They feel connected to them. Characters in gaming are a reflection of themselves.

I had quite a few iterations on the idea. In one, the toy itself was a little robot, and it would move. Another one had tons of accessories. After many hours of testing, I decided to keep it really simple, and have very few accessories, that, depending on combination and placement, would achieve different things.

This is a very summarized version of my process. If you want to read more, I have a whole blog post explaining how I got to the final concept.

Molina: I don’t see this as an ultimate solution, but rather just one step into a world where everyday objects can be our interfaces to interact with the digital world. We don’t only have to use abstract, all-purpose interfaces, like screens. But I’m interested in the idea of evocative interfaces, especially for children, to help them avoid losing contact with their real, three-dimensional world.

Our toys take an important part in our lives as children, and even as we grow up. They are often a child’s friends and companions, or a representation of themselves, while they are playing. Characters in gaming also have a similar effect. I wanted to use that connection and expand upon it. Ziff can go on adventures even when the screen is turned off, and it can be used with other toys, leaving the child to imagine all that Ziff can be, and all she can so.

There are some physical and technical implications of this new interaction in the gameplay, but I found the main difference, for the children that tested the game, was in their heads. They immediately start thinking of new behaviors for Ziff, and what they could do with their other toys.

Molina: There were a lot of rules and behaviors to adapt to. When trying the game out with the keyboard, everything is immediate. I would just press a key and the character would change.

When playing with the toy, though, it became much more complicated. I have to think about where the attention of the player is at all times, exactly where the player’s eyes will be looking.

The level design has to consider the time it takes to make any physical change, and I needed to consider all the possibilities, not just the “right ones”. The game should react to whatever configuration the child makes, and should give you some space to experiment, and learn by trial and error. Every level has to have different environments to motivate the player to change configuration.

I did not want the toy to end up like a console controller, so adding many buttons was not an option, therefore the game works with just one button. There was a lot of back and forth, mediating between the toy and the game while trying to make both of them fun and keeping them simple.

Molina: I had to prioritize. The physical version is a toy first, and a controller second. This means it’s not as ergonomic as a console controller, and, like I mentioned before, it shouldn’t be full of buttons and inputs. The most important thing was that it would look and feel like a toy, and would be fun to play with even without the digital game.

Magnets were a great solution for this. They snap together, which lets you adapt the toy without having to look at it, and they are also intrinsically fun. Or maybe I’m just a magnet geek… There’s something pretty magical about magnets and their crazy invisible forces.

Designing the toy and character was challenging and fun. Ziff had to have a simple shape, neither male nor female, and shouldn’t resemble any specific creature, since it could fly, swim AND walk! Oh, and travel through space. I just needed to define the top, bottom, front, back, and leg placement. Other than that, it’s pretty open to the child’s imagination to define what it is (I have heard all kinds of creatures it supposedly resembles).

Molina: I am NO expert in the matter, but it’s still fun to wonder about this.

In gaming, I believe most controllers will be abstract and multipurpose, like standard computer and console controllers, and mobile devices. Definitely the technology will improve, and we will have more sensors, more haptic feedback, maybe even some augmented and virtual reality. The great thing about these generic interfaces is they are usually ergonomical and you don’t have to buy a new one for each game you want to play. That seems like reason enough to keep them.

I think that, more and more, we will use other kinds of inputs in our games like location, time, weather, and physical environment. Lots of games are already doing this, but I believe it will be more common.

There is also another movement that takes advantage of the Internet of Things. Gaming is not the center of this trend, but it does feel its impact. With IoT, interfaces don’t need to be so generic and abstract anymore. I think people will come up with crazy things they can do with everyday objects. For children and education, many toys will become interfaces for something else. Maybe this is just my wishful thinking, and precisely the reason why I came up with Ziff, but that would be fun to see.

Go here to read more interviews with developers who will be showcasing their unique controllers at Alt.CTRL.GDC.

Read more about:

event-gdcYou May Also Like