Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

“The goal of this talk is to help you develop accurate empathy,” said Ubisoft's Jason VandenBerghe. “To understand what’s going on in your players’ minds so you can make accurate design decisions.”

Ubisoft creative director Jason VandenBerghe has a passion for player psychology. Beyond his game development work at Ubisoft (where he's currently a director on For Honor) he's known for applying the "Big 5" model some psychologists use to map human psychology to game design.

Back in 2012 he presented his adaptation at GDC as the "5 Domains of Play," and this week he returned to GDC to update his model based on what he'd learned in the interim -- and offer some potentially useful advice to fellow designers.

“This model is not about making better game design; this model is about making better game designers,” said VandenBerghe. “These designers will internalize these models and make better decisions, because they will understand their players better.”

VandenBerghe suggested game makers tend to move through three phases of understanding their players: the outsider phase (“ha ha, look at them!”), the empathy phase, and the accurate empathy phase.

“The goal of this talk is to help you develop accurate empathy,” said VandenBerghe. “To understand what’s going on in your players’ minds so you can make accurate design decisions.”

He opened with a quick refresher on the “Big 5” model of understanding human psychology, which seeks to quantify (through research like questionnaires, Q&A etc.) people through five big lenses: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness and Nuuroticism ( or O.C.E.A.N, for short).

VandenBerghe went on to show how each of those five factors could be subdivided into six facets -- “imagination” is a facet of your Openness to Experience, for example.

He said he’d given dozens of people a test about their game preferences, over the course of several years. ("turns out that’s called qualititve research, in science,” said VandenBerghe. “I had no idea,") in order to correlate players' five-factor profiles with their preferences for games and how they play them.

“What I was trying to do is, I was trying to say this correlates -- if you have a high imagination score you prefer fantasy, if you have a low score you prefer realism,” said VandenBerghe. “It seems obvious, but it also turns out to be kind of true.”

But it also turned out, in hindsight, to be kind of unwieldy and not always as accurate as it could be.

“Did the model make communication easier? Absolutely, yes. It’s the primary value this model has," said VandenBerghe. "Did it prove to be a complete match? Did it cover all of our bases? No. Not even close.”

"You don't keep playing for the same reasons you start playing -- your taste changes"

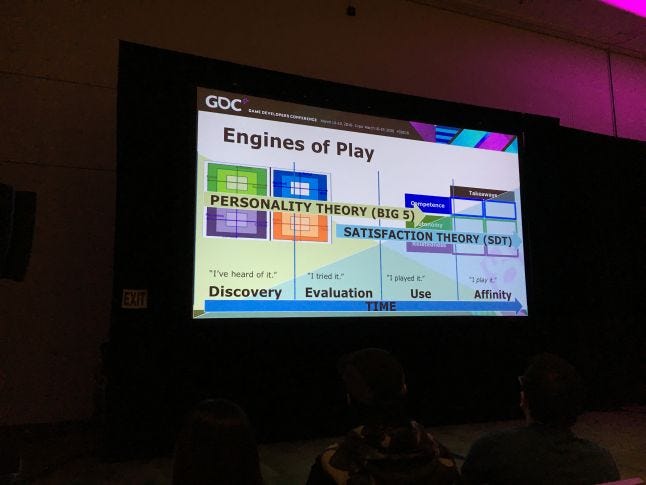

So this week Vandenberghe sought to “patch” his earlier Engines of Play model. For example, he points out that his earlier models didn't really model why players would (or wouldn't) engage with a game over time.

“You don’t keep playing for the same reasons you start playing,” said Vandenberghe. “Your taste changes.”

What if you want to try and model that out ahead of time, during production? VandenBerghe offers his model of “the player’s journey” from Discovery (“I’ve heard of that game”) to Evaluation (“Yeah, I’ve tried that game”) to Use (“Oh yeah, I played that!”) to finally, Affinity -- the point at which players self-describe not as, say, “playing Bloodborne” but as a “Bloodborne player.”

Of course, as someone gets deeper and deeper into a game, the value of its ability to cater to their specific interests -- it's ability to satisfy their taste for a certain type of game -- drops.

“As time goes on, the impact of ‘taste satisfaction’ is going to go down,” said VandenBerghe. “The longer you play a game, the less you care if it matches your individual tastes.”

So if a game can become less satisfying over time, how do you quantify how satisfying it is to play in the first place? Of course, VandenBerghe has a model for this: a sort of “satisfaction map” of the three main sources for human motivation, based on the self-determination theory (or SDT) used by some psychologists.

“If you’re a human being, you have these,” said VandenBerghe. “This is a test.”

Competence: The universal want to seek to control outcomes and experience mastery. In Minecraft, for example, this might be satisfied by a player successfully surviving in-game and crafting things.

Autonomy: The universal urge to be causal agents of one’s own life and act in harmony with one’s integrated self. So in Minecraft, you might see this satisfied by the players’ ability to create and modify their own world, and craft their own creations -- building a scale replica of Star Trek’s Enterprise, for example.

Relatedness: The universal want to interact, be connected to, and experience caring for others. So for Minecraft, that might be satisfied by players having shared experiences playing with each other and having themselves placed on a public canvas.

But relatedness, in VandenBerghe’s eyes, “is not satisfied by social stimulation. Relateness is satisfied by knowing where you fit into the world.”

This three-pronged “satisfaction map” is a good way to communicate early on about what you intend the core values of your game to be, advises VandenBerghe, which can concretely benefit your production process.

What seems most important here, at least in VandenBerghe’s eyes, is that by thinking through game design in this way you come to clearly understand that you are making your game for certain people and not making your game for other people -- then you stop letting the latter category influence your work.

VandneBerghe acknowledges that his work is not comprehensive, and that there are missing “engines” of player motivation in his model, including (but not limited to) the appeal of various forms of fun. I also would note that this is just a quick overview of some highlights from his talk, and that those interested in learning more about these concepts should check out VandenBerghe's website, where he hosts slides and links to videos of his talks on the topic.

“Go and do the research,” said VandenBerghe. “If you’re interested, you really should.”

And of course, developing a sharper understanding of why players are motivated to do certain things -- accurate empathy -- and why those motivations change over time is about more than games.

“Empathy will make you a better person," said VandenBerghe. "And that’s the real point of this talk.”

Read more about:

event-gdcYou May Also Like