Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Escape Room (ER) games deliver greater immersion than a videogame, and more agency than a theatrical play, yet the narrative told in many ERs is little more than a cliched action movie plot. Can ERs use classical dramatic structure to tell better stories?

Every game tells a story.

The story told by most videogames is obvious and explicit; played out in real-time by the actions of the player’s avatar, narrated in cut-scenes, or recounted by in-game characters and artefacts. In tabletop games, the story typically has a more symbolic and abstract representation, as in the tales of battles fought between opposing armies that are interwoven into the terminology and mechanics of every game of chess. In both these examples, the player’s experience of the story is mediated through some sort of layer of abstraction - the in-game graphic depiction of the player’s character, or the pieces on the game board. In contrast, players in a real-life Escape Room (ER) have a direct physical presence in the game, and they experience its narrative unfolding first-hand. What then does that mean for storytelling and dramatic structure in escape room games?

There has been some recent commentary on the subject of diegetic and mimetic storytelling in escape rooms; in literature, a diegetic narrative in one in which the audience is told a story (“Once upon a time…”), whereas in a mimetic narrative, the audience is shown events that occur. Therefore, ER narratives can typically be considered to be mimetic - the story progresses through actions and events that occur in real-time in front of the players. However, an ER player cannot be compared to the audience in a theatrical play, passively consuming what they are shown; rather, an ER player assumes the starring role in the story, and it is as a direct result of their decisions and actions that the narrative progresses.

The story told in an escape room game is typically not subtle; it is normally akin to the plot of a Hollywood action movie - intense, action-packed, brash - based around some immediate and often perilous dramatic situation. Common ER scenarios include a bomb placed beneath the city, an imminent virus outbreak, or a maniacal madman hell-bent on destruction; the storylines of which can be summarised within a sentence or two. The use of such clichéd plots can perhaps be excused considering that escape room games typically last only one hour, and there is little time to expose detailed backstory, complex character motivations, or dramatic twists. It is also true that some players are attracted to ER predominantly as a physical or mental puzzle-solving activity, and the inclusion of a story is simply to provide a thematic link and the most minimal of contextual motivations for the player to engage in solving the puzzles presented to them - not to provide deep, complex narratives.

However, there is evidence that some players seek a more meaningful experience, and want to be immersed in a coherent, believable story, rich with lore and containing complex characters and situations. The agency that players have in deciding how that story develops presents new opportunities and challenges for escape room designers and, as the escape room industry matures and its designers become more skilled, we find that they are also becoming more experimental and ambitious with the stories they are trying to tell. In this article, I’ll take a short look at how classical dramatic structure can be applied to shape an escape room experience, and perhaps help to facilitate those more complex narratives.

When we first learn to write stories at school, we are taught that they conform to a basic narrative structure: stories have a beginning, a middle, and an end. This three-part structure can be attributed all the way back to Aristotle’s analysis of Greek tragedies in around 335 BC.

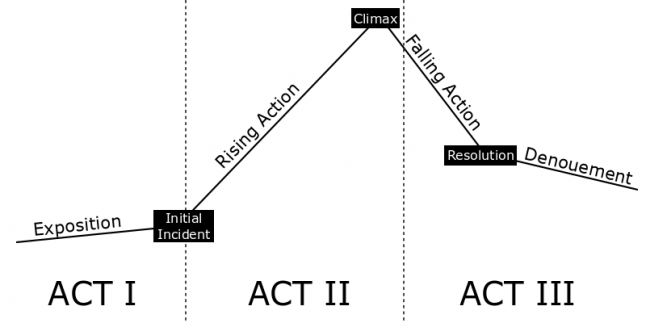

Subsequent models of dramatic structure have been proposed, such as that put forward by German playwright Gustav Freytag in Die Technik des Dramas (1863). This model has become commonly known as “Freytag’s pyramid”, and is illustrated below:

Freytag's model of dramatic structure, as described in Die Technik des Dramas. View the full manuscript online at archive.org.

Freytag’s model defines sections of dramatic action, separated by key events, which can be positioned and aligned to sections of the Three Act Structure. Freytag’s model is often represented as a 2D graph in which the x-axis shows progression through the story, and the y-axis shows emotional engagement or tension. The resulting curve depicts the typical dramatic arc rising and falling as a “pyramid”. Freytag's analysis was originally based on studies of ancient Greek and Shakespearean drama, but it has subsequently been applied to short stories and novels, as well as contemporary and classic films. So, why not escape rooms?

Freytag’s dramatic model begins with the exposition, which is where the main characters are introduced, the time and place in which the story takes place is set, as well as other contextual background information and lore relevant to the action. In an escape room, these elements of theme and backstory are often described on the room’s website, or presented during a pre-game introductory briefing by a gamesmaster or pre-recorded video introduction.

The exposition normally takes place prior to entering the main room itself - in a pre-game area or lobby, and are often presented to the player in a diegetic manner in which the background history of events leading up to the scenario that takes place in the room are narrated to the player. There are exceptions to this, however: in Oubliette - a highly-praised and now sadly-closed escape room in London, players started in an ante-room in which they had to bribe an in-game character with food coupons to gain access to the main room. This brief interaction effectively introduced the time and place in which the game took place (a dystopian, Orwellian near-future), provided an explanation for the time limit placed on players (the window of time within which the character would leave to find and eat food using the coupons given), and also provided players with the motivation for their purpose in the room beyond - all crucial elements in the exposition of the story.

The exposition is followed by the initial incident, which marks the end of the story setup and sets up what is known as the dramatic question - what do the protagonists have to do to solve the problem they face? “Will the girl get the boy?”, “Will the zombie horde be defeated?” etc. The dramatic question is often presented to the team of escape room players by a gamesmaster just at the point that they enter the room, which also serves to set their objectives in the game. The success (or otherwise) of the players in achieving the gameplay objectives will determine how the dramatic question is resolved in the narrative.

Act II is where the rising action of the story occurs, in which the protagonists (the players, in our case) are faced with continuous, escalating conflict as they try to overcome the antagonist. It is this section of the narrative that typically constitutes the overwhelming majority of an escape room experience - solving puzzles, discovering items, and revealing new areas in pursuit of the goal. Clever room and puzzle design can focus players’ attention on the increasing urgency of the tasks at hand, the perilous situation becoming more tense as the clock ticks down (often displayed on a monitor in the room), and accompanied by ever more dramatic theatrical music, lighting, and effects.

The dramatic tension in the room increases higher and higher up to the climax, which is the emotional peak of the story - the showdown with the big baddy, cutting the wire to defuse the bomb, reaching into the abyss to recover the lost artefact - this is typically represented as the final puzzle in an escape room, and is the thrilling moment the story has been building towards. But while it might be the pinnacle of emotional engagement, the climax is not the end of the story arc in Freytag’s model - there are still matters to resolve and loose ends to tie up.

Following the climax, the action does not abruptly end and calm immediately become restored. Instead, Freytag’s model identifies a period of falling action that results from the climax, which, though receding, can still be exciting (for example, having disarmed the death-ray during the climax, the heroes still need to escape the building before it collapses in the falling action).

The falling action eventually leads to the resolution of the dramatic question first asked: have the players - the protagonists of the story - succeeded or failed in achieving their objective?

Even after having resolved the principle dramatic question, there are often still additional subplots and minor details that also need tying up (or, perhaps, deliberately left as unresolved cliffhangers that could be addressed in a sequel), which are addressed in the denouement. If the story has a morale, it is in this final stage of the drama where it becomes explicit (“the team overcame the odds, but were only able to do so by working together!”), and documents how the characters have grown as a result of the experiences they’ve had.

While the dramatic structure of most escape rooms initially appears to conform to the arc described by Freytag’s Pyramid, this typically only holds true as far as the climax of the story; ER designers are becoming relatively skilled at onboarding players during the initial introduction, inviting them into the make-believe world into which they will shortly enter, and immersing them into the roles they will adopt. As production values in escape rooms increase, we have also witnessed ERs borrowing techniques from film and theatre to grip players’ attention and build rising tension up to a climactic final puzzle. However, there rarely seems to be the same attention paid to the game ending and, following the climax, the subsequent resolution and ultimate conclusion of the dramatic narrative is all too often conspicuously absent from escape room games. Games often finish abruptly, signified by a brief theatrical spectacle before the team are dumped back into the real world just moments after solving the final puzzle. This sometimes leaves players questioning whether the game is really over, or what the final outcome was.

To draw a comparison to a James Bond movie (a standard against which many escape rooms would happily be judged), after the supervillain’s plan is foiled during the climax and the antagonist meets their inevitable comeuppance, the overwhelming majority of James Bond films draw to a close with a scene in which we see 007 reclining salaciously in some glamorous setting, making a double entendre before rolling around half-naked with the Bond girl. Trite though the scene may be, its purpose is to remind the audience of the strength of 007's character in surviving unscathed from his experience, and having retained his usual (misogynistic) self despite many near-death experiences. And, even though this scene may only constitute a tiny fraction of the overall story, it draws a conclusion and cathartic release, together with some light-hearted relief to the audience. Even the most basic and minimal of action narratives deserve a closure of sorts, and this holds true for escape rooms too: so, you saved the citizens of the doomed city, or recovered the priceless stolen artefact - but what happened next? How were you rewarded for your deeds, and how was the evildoer responsible punished?

Furthermore, as escape rooms attempt to tackle more difficult subjects (e.g. The Divide - an ER game concerning homelessness and social inequality), the way in which the narrative ends, and the dramatic note on which players leave the experience needs to be given equal, if not greater, attention than the manner in which they enter. It is worth mentioning that Freytag presents only one model of dramatic structure - it is not authoritative, and there are plenty of examples that do not follow it (the works of Chekhov, for example, rarely reach a conventional notion of resolution). Nevertheless, there are certainly things that escape room designers can learn, and techniques that can be borrowed, from considering the classical model of dramatic structure, particularly with regard to the conclusion of the game.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like