Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

Common pitfalls encountered when attempting to reconcile the narrative and gameplay elements of games in blockbuster games

Games can be considered to be split up into two types of elements: ludic and narrative. Ludic refers to the gameplay elements and how the player interacts with the game. Narrative refers to the story, objectives, characters etc. Tetris for example is almost purely ludic. In contrast Heavy Rain is heavily narrative.

Most blockbusters tend to be sophisticated in both fields and try and marry the two. In this post I want to talk about points where this marriage can go wrong. I am going to discuss this in five sections:

Ludonarrative Dissonance

How Players Play

How Developers Create

What The Player Knows

The Character and the Player

It's worth pointing out that I am going to say bad things about very good games. I have thoroughly enjoyed every game mentioned here. I offer my criticism to elucidate my ideas on how to improve games in general not to highlight particularly bad points of the games.

Clint Hocking coined the term in ("Ludonarrative Dissonance in Bioshock"). This is essentially when the narrative elements and the ludic elements are in conflict. His contention was that this is a problem with "Bioshock". He claims that there are two contracts on offer to the player: a personal power-seeking contract and a narrative contract to behave altruistically. The argument being that this is in conflict with the ludic contract.

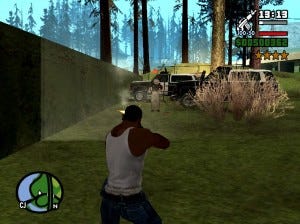

I don't really agree with this assessment of Bioshock but Ludonarrative dissonance is an important concept. There are games that I have played where the narrative and the gameplay are at odds. No matter how much I enjoy each individually the incompatibility is jarring. For example "GTA: San Andreas" is a redemption story which necessitates a headcount of thousands. The story is about CJ making a new start while the player must commit genocide to get to the redemptive ending. This is a ludonarrative dissonance.

Bringing The Mechanics Into The Narrative

Raph Koster points out in one of his posts that "Narrative Is Not A Game Mechanic". This is a very important point. Narrative is for contextualising the action and for providing feedback. You don't use narrative in order to improve the ludic elements of a game but to contextualise them.

Interestingly Walt Williams in his GDC Talk "We Are Not Heroes: Contextualising Violence Through Narrative" points out that the converse can be true i.e. the mechanics of a game can be a narrative element. That is the side of the equation that we often miss.

In "Spec Ops: The Line" the shooting of people is a key narrative element. "Spec Ops" the game is about shooting people. "Spec Ops" the story deals with this fact. As the body count mounts up and Walker becomes more pro-active, it gets harder to justify the killing and the narrative addresses this. The fact that the player is killing people is a pivotal element of the story.

This is part of the reason why I think "Spec Ops: The Line" is so narratively satisfying. It doesn't have as much of a disconnect between the gameplay and the story as there is in other games.

There are other interesting examples of mechanics being "brought into the story". The dagger in "Prince Of Persia: Sands Of Time" brings the act of replay into the narrative. The dagger is an in-world tool that rewinds the time of the story and allows the player to try again. The fact that the player tries the same jumping puzzle multiple times is no longer disconnected from the narrative.

Considering the effect of your ludic elements on your narrative (and vice versa) is key to making the two sides work well together.

Players often experience the narrative of a game in a different way to what we intend. There are three parts of this I'm going to address individually:

Players fail

Games are usually played over multiple sittings

Players don't finish games.

Players fail

Perhaps the most obvious problem with how players play is that they fail. Players die in the game mid-narrative. The standard way of dealing with failure or death is restarting from a checkpoint - the narrative elements making no attempt to address this.

Some games are happy to just consider this a part of the medium but others are making some attempts to address it. "Prince Of Persia: Sands Of Time" brings it within the narrative. "Heavy Rain" allows characters to die and proceeds down a different path. "Batman : Arkham Asylum" uses the grappling hook to save Batman from fatal falls.

Restarting is so ingrained in gaming culture that it's often hard to see the point of addressing it. But I think it's worth thinking about. If you can smooth out the restarts by bringing them into the narrative I think you can offer a better experience.

Also "fail" does not necessarily mean die. Players can fail in all kinds of ways. They can fail to find the exit. They can fail to work out the puzzle. They can fail to perform the action in the way you expect. When creating a narrative we should consider how failing fits in.

Games are usually played over multiple sittings

Games are rarely completed in one sitting. They may be completed over days, weeks, months or even years. When we create a narrative for a 10 hour game we may have to consider a narrative that will play out for the player over a far longer time.

I have seen so many games with labyrinthine plots that I've ended up playing over the course of months. I dread to think how many brilliant third-act betrayals have been lost on me simply because I had no idea what the characters were talking about.

Even a relatively simple plot can be problematic when stretched out over months.

When we consider the plot of a game we should consider that in many circumstances this will play out at a totally different pace to how we wrote it.

Some developers are beginning to treat their games as more episodic in form. Taking inspiration from a TV series that plays out over many seasons may match the form of play a lot better than the movie inspiration that we see in a lot of games. I am surprised Alan Wake's "previously on Alan Wake" hasn't been adopted by more games.

People Don't Finish Games

It's very hard to get really good data on how many people get to the end of games but it seems from the information out there that a lot of people don't. Bioware reported that 42% of players completed Mass Effect 3 and 56% completed Mass Effect 2 (source). In a survey of 14,000 XBox live users 26% completed "GTA IV" (source).

If you think about someone buying a similarly well-respected, enjoyable and well-reviewed film (say The Dark Knight) it seems utterly inconceivable that only 26% of people will get to the end.

And yet lots of games seem to be structured like movies that gradually build up to a big narrative climax. Maybe we should consider different narrative structures that are more compatible with how our audience experience games.

Of course another solution is to get more people to the end of the game. Either way I think it's clear there is an issue to tackle.

Games are long

Distractions

Games Are Long

An average length game is maybe five times the length of a movie. Take a look at a random sample on www.howlongtobeat.com and you will see that many games are five,ten,twenty or more times longer than movies. "GTA IV" clocks in at around 28 hours.

When creating a story we should be very mindful that our hour of cut-scenes is going to play out over a long time. Coupled with the fact that players play it in multiple sittings we may consider dialling back the complexity of the plot or have lots of complex mini-arcs in an overall simple arc. The GTA series does a really good job of this.

Distractions

A lot of modern games have things to do other than the main quest. This makes perfect sense. After all giving the player fun things to do in a game is a good idea. But it's worth bearing in mind what effect this has on your narrative. I find that these side-quests often destroy the pacing of the narrative. "Tomb Raider" is full of things to do: salvage to pick up, animals to hunt, relics to find, GPS caches to collect, tombs to raid. But the problem with this is that when the narrative says "Save X urgently" I find myself still playing at the same pace that the side-quests have instilled in me. As I race to the temple I notice a relic, steer Lara towards it and Lara calmly tells me all about its origins. This completely destroys the sense of urgency the narrative is trying to instill.

The gameplay is damaging the narrative. When considering your narrative and your gameplay you should consider whether the side-quests are going to distract and if there is anyway to mitigate it. For example if something is particularly urgent maybe a countdown would be appropriate.

This next point is a strange one. It doesn't usually shatter the suspension of disbelief but nibbles away at it. It's the disconnect of knowledge between the main character and the player. Put simply; sometimes the player has better information than the character and sometimes the character has better information than the player. There are countless examples of both of these but I've noticed them both in the last two games I played.

In "Bioshock Infinite" Booker DeWitt alludes to a history that he is privy to and the player is not. The player is in control of Booker's eyes, his legs and his arms, creating the illusion that they are the protagonist. However they don't know what Booker is talking about so the illusion is broken.

In "Tomb Raider" Lara tells the player "I can't do that yet" when the player presses a button. This raises some questions. What has compelled her to try and do something she can't do? Who is she talking to when she says she can't do it? And how does she know that at some future time she will be able to do it? I can completely understand why it's useful information for the player to have but having Lara saying it out loud is frankly bizarre.

There is also an example of the player having better information than the character in "Tomb Raider". There is a point in the game where the player must walk Lara into a trap. Lara is turned upside down and they have to shoot the advancing bad guys to advance. If Lara dies during this shoot out the player is restarted at a point immediately before the trap. Their only option is to walk Lara into the trap again. The player knows this but Lara is completely unaware. This creates a disconnect between the player and the character. If the save had instead been after the trap was sprung this problem would have been removed. The player would not need to act on the lack of information that the game has thrust upon them.

There's a wonderful bit in Rayman 3 where Murfy reads the user manual to Rayman as they progress through the first level.

"It says here that you hit the jump button in order to jump."

This is all a bit fourth-wall breaking but does hilariously draw attention to the player/character disconnect. These examples I have drawn may not seem that important but I think the concept of the player/character disconnect is worth thinking about when you are designing a game.

When thinking about game narrative I think it is extremely important to be clear about the distinction between the player and the character. It's easy to lazily use the terms interchangeably. The problem with this is that it masks a problem....

As technology and production values have improved the ability to create incredibly beautiful cutscenes has been seductive. Now we can render the character doing absolutely amazing things. But that's the problem. It's the character doing those things not the player.

I'm not against cutscenes. I think they are invaluable in establishing a situation and creating investment in the story. However I sometimes feel developers convince themselves that if our character does something amazing in a cutscene it's as satisfying as the player achieving something amazing with the core mechanics. I guess it depends on the core mechanics - but in general I would say this is not true.

This lack of interaction with these amazing things was, of course, recognised and Quick Time Events were introduced. Raph Koster points out in "Narrative Is Not A Game Mechanic" that these are basically a game of Whack-A-Mole.

They are usually pass/fail situations and the reward is proceeding in the game. When thinking about adding them I think it's worth considering what they add from a narrative and gameplay perspective.

From a narrative perspective I think you do yourself two disservices by using QTEs. Firstly you distract the player from the narrative by getting them to play Whack-A-Mole at the same time as they are trying to watch your dramatic moment. Secondly you make it possible to fail the cutscene. Seeing cutscenes over and over again is a miserable experience.

From a gameplay perspective you get a very simple mini-game. The screen tells you the button to press/stick to waggle and you have a short period of time to do it. You are interacting with the game (albeit in a simple way). Certain QTEs are slightly more sophisticated and attempt some link to the action e.g. Hammer CROSS for a strength test. Even this is a pretty light.

When adding QTEs I think we should consider them from both a narrative and gameplay perspective and see if on balance they add what we want them to add. Would we be better served by spending extra effort creating a sequence with more sophisticated control or simply show the player the exciting moment?

The most bizarre examples I have seen are where the player is presented a QTE that replaces the core mechanic! Instead of aiming and shooting at the final boss' head I am told to press an arbitrary button to do it. The game has given me the tools to do the job and then denied me the ability to do it.

Heavy Rain did some interesting things with them by having long branching and joining paths of them during action sequences - turning them into more than pass/fail - but they were still not satisfying in a press-by-press sense. Heavy Rain, wonderful as it is, is more of an interactive story than a game.

QTEs are far from a terrible idea I just think the use of them is sometimes based on faulty assumptions.

Maybe we should focus more time, effort and money on making an exciting experience for the player than showing them what an exciting experience the character is having.

There are choices and compromises to be made when creating a narrative game. Each individual will add different weight to the ones I have highlighted. But hopefully I have highlighted some areas where there is a choice to be made and convinced you that it is worth making.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like