Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

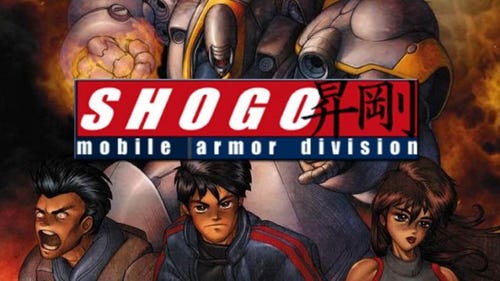

A game analysis that talks about mecha anime and how Monolith Productions' Shogo: Mobile Armor Division faithfully captures the genre's essence.

NOTE: This article was taken directly from my academic paper, “Effort Upon Effort: Japanese Influences in Western First-Person Shooters”, which was originally published on December 17, 2015.

In the early 2000s, the Japanese government started to evaluate the value of the country’s popular culture industry following international successes in anime/manga (Pokemon, Dragonball), games (Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda and Super Mario series) and films (Spirited Away, Ringu). Realizing that its cultural influence expanded despite the economic setbacks of the Lost Decade, Japan sought to promote the idea of ‘Cool Japan’, an expression of its emergent status as a cultural superpower. For the next dozen years, the Japanese government made use of its soft power and ‘Cool Japan’ strategy to boost cultural exports from its creative industries, including one of its oldest and most influential anime genres: mecha (an abbreviation for the English word ‘mechanical’).

Since their inception, mecha anime and manga have dazzled fans with epic tales of battles fought by giant robots. Evidence of the genre’s popularity is readily apparent in Japanese society, from the life-sized replicas of giant robots in public spaces to the Japanese Liberal Democratic Party’s efforts to make piloted, two-legged walking humanoid robots a reality. Such war machines serve as containers for spiritual and physical transcendence for the pilots or operators who control them.

The origins of Japanese mecha can be traced to the end of World War II, when Japan witnessed the destructive power of modern technology in the form of atomic bombs that obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These dramatic events served as an inspiration for Japanese survivors who later became cartoonists. During Japan’s Occupation and post-Occupation years (1945-early 60s), an explosion of artistic creativity occurred in the manga industry, possibly aided by the medium’s exclusion from U.S. Occupation censorship policies. These policies forbade depictions of war and Japanese nationalism, despite the fact that Article 21 of the Japanese Constitution prohibited all forms of censorship. One artist, Mitsuteru Yokoyama, took advantage of this loophole to craft one of the most influential mangas of all time.

Yokoyama was motivated to become a cartoonist following the breakthrough success of Osamu Tezuka’s Mighty Atom (Astro Boy, 1952), the story of an android who fought crime with mechanical powers yet was capable of displaying human emotions, essentially acting as an interface between man and machine. Yokoyama took a different approach, drawing heavily from his childhood encounters with war, technology and film. As a child, Yokoyama was astonished by the terrifying power of the B-29 bombers that reduced his hometown of Kobe to ashes, as well as the Wunderwaffe (wonder weapons) that the Nazis built during WWII. The movie Frankenstein (Universal, 1931) convinced Yokoyama that the titular monster did not have a will of its own, but rather followed the commands of its controller without taking morality into account. In contrast to Astro Boy’s human demeanor and moral compass, Yokoyama crafted a giant, remote-controlled robot that was expressionless, emotionless, and unbeatable, similar to the Martian fighting machines in H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds.

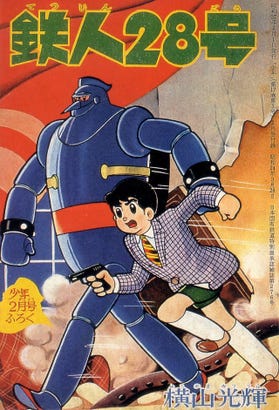

The result was Tetsujin 28-go (Iron Man No. 28, 1956), a parable about technology’s dangers and benefits. It told the story of Shotaro Kaneda, a boy detective who fought criminals by commanding the titular robot by remote control. Tetsujin was created by Shotaro’s late father as a WWII superweapon that would have turned the conflict in Japan’s favor. Their adventures were depicted in fast-paced, action-filled panels reminiscent of a well-edited action film.

Much of Tetsujin 28-go’s appeal could be attributed to the strong bond between Shotaro and Tetsujin, enhanced by the robot’s benign and knight-like design, suggesting an avatar of unstoppable justice which readers could identify with and cheer for. Tetsujin 28-go was the first instance of a Japanese cartoon based on the idea of a giant humanoid robot controlled by a human being, with the former acting as a tool for the latter to use for realizing his fullest potential. This concept could be seen as a metaphor for a resurgent Japan, reawakening like a giant from the rubble of WWII, evoking a strong sense of empowerment through technological means that would define subsequent mecha anime/manga works.

If Yokoyama established a link between man and machine with Tetsujin 28-go, then Go Nagai forged that link into a union. Having read both Mighty Atom and Tetsujin 28-go as a youngster, Nagai sought to create his own robot manga. One day, while waiting to cross a street, Nagai contemplated the backed-up traffic and mused about how the drivers were wishing for some way to get past the other cars. This inspired a novel idea: what if the car suddenly transformed into a robot that a person could ride and control like a regular vehicle? Fortuitously coinciding with the spread of personal car and motorbike ownership in Japan, Nagai’s concept — a pilot sharing the body of a robot — made the man-machine bond both figurative and literal. The resulting manga, Mazinger Z (Tranzor Z, 1972) would prove to be the next big evolution in the mecha genre.

Mazinger Z told the story of Koji Kabuto, an orphaned schoolboy who stumbles upon the titular giant robot in his grandfather’s secret lab. The robot’s name evoked the image of a majin (demon god) with its similar-sounding syllables (‘Ma’ meaning ‘demon’ and ‘Jin’ meaning ‘god’), reinforcing the idea of a machine built by humans in need of protection that also appears as an ancient, unfathomable being. This is echoed by the dying words of Koji’s grandfather: “With this mechanical monster, Mazinger Z… You have the power to impose what you will on anyone!”.

Mazinger’s appearance was striking for its time: a brightly colored mechanical juggernaut ornamented with a mixture of military equipment and samurai armor. Its design resembled the sleek new roadways, bullet trains and skyscrapers being built in Japan during the 1970s, an era of rapid industrial development. A small hovercraft docked on the robot’s head housed Koji, who acted as its ‘brain,’ directing its powers via voice command. This established Mazinger as more than just a humanoid war machine. It served as an extension of the pilot’s abilities and will, preserving its mechanical identity while symbolizing a powerful symbiosis between man and machine.

Mazinger Z’s formula proved successful, spawning numerous imitators such as Brave Raideen, Combattler V, and Dangard Ace. But before the decade ended, another development in the genre appeared that surpassed Nagai’s work in both popularity and influence. Created by Yoshiyuki Tomino who believed that the predictable, menace-of-the-week storylines of commercial mecha had grown stale, Mobile Suit Gundam represented a massive shift in both tone and scope. In place of isolated weekly episodes, Gundam presented a continuously developing story with a more ambiguous sense of morality that targeted the lines between good and evil and the effects of war on the people who fought. Its complex story focused on the war between the Principality of Zeon and the Earth Federation, with the latter unveiling a new giant robot known as the RX-78-2 Gundam, piloted by the teenage civilian mechanic Amuro Ray. Instead of humans using machines to fight off evil aliens, Gundam had humans fighting humans, with both sides having their own ideological motivations. By favoring realism over fantasy, Gundam felt grittier and deeper than Mazinger Z. This new approach led to the splintering of the mecha genre into two subgenres: Super Robot and Real Robot.

Whereas Super Robot stories focus on near-godlike mechs in fantastical scenarios, the Real Robot subgenre emphasizes drama, human characterization, a realistic civil-war-in-space backdrop, and plausible mech creations that required adjustments and repairs. Real Robot mechs are firmly grounded in conventional physics and credible technological advances. They make use of oversized versions of traditional firearms like rifles and cannons, manually operated rather than voice-activated, with realistic technical limitations (e.g. ammo, fuel). This could lead to moments when the protagonist might actually lose a battle if their machine was not properly operated and maintained. This is in contrast to Super Robot works, which depict mechs as near-invincible entities that only seem to sustain damage when needed to drive the plot.

Gundam mechs were designated by numbers, not names. This highlights another important difference between Super Robot and Real Robot: the former treats mechs as unique, semi-mystical beings, whereas the latter considers them mass-produced tools of war that take a narrative backseat to the character development of their human pilots. Despite initially low ratings, these distinctive qualities led to the Gundam series becoming a smash hit, paving the way for more complex mech series such as Macross, Robotech, Patlabor, and Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Soon after the appearance of Real Robot manga/anime, a geek subculture called ‘otaku’ developed in Japan and spread to the West, exposing international audiences to the distinct aesthetic qualities of Japanese mecha. Unlike clunky, lumbering Western mechs such as those found in Battletech, Japanese mechs were anthropomorphic and highly mobile entities. They espoused recognizable classes of people — snipers, soldiers, knights, etc. — including symbols of Japanese culture like the samurai. This can be seen on the RX-78-2 from Mobile Suit Gundam, which sported a fluted helmet and a skirt of armored plates on its torso.

Motion was equally important. Like the samurai sword, the mobility of Japanese mechs was managed by the user within, whose own bodily control and prowess determined the mech’s amplified analogues of human action. This granted the mechs a striking (if occasionally incongruous) agility as the humans inside the mechs became empowered and amplified, reflecting the man-machine merger whose symbolic effectiveness would be diluted if the machine displayed an inhuman design like those of many Western mechs. The Japanese mecha philosophy promotes the idea of having people work alongside powerful machines with a familiar human shape, a desire that is associated with Japan’s long religious history and culture.

Much like the Western superhero genre, with characters like Superman and Wonder Woman inspired by Judeo-Christian ideals of an anthropomorphized God, the Japanese mecha genre is influenced by East Asian culture and religion, specifically Shinto and Buddhism. Both the Shinto concept of revering natural phenomena, including non-humans, as kami (gods) and the worshipping of carved images of Buddha in Japan suggest the protean notion of inner energy that can manifest itself in a mechanical form that may be anthropoid in shape and even showcase some human traits. This harnessing of power can be seen as a representation of ki, the energy possessed by every person and object in the world, which can be stored, released, and controlled through bodily channeling and disciplinary exercise. This is the Japanese mech’s most distinctive characteristic: it is the tool through which its pilot expresses their power and will to overcome by bonding with the machine. This intimate union imbues the mech with a ‘soul’ that controls its advanced abilities, gratifying both the pilot’s need and the viewer’s fantasy of power, authority, and technological competence.

Shogo: Mobile Armor Division offers an example of a Western FPS that captures the thrilling essence of Japanese mecha works like Patlabor, Macross Plus, and Venus Wars by combining speedy, agile mechs with the fast-paced gameplay of Doom. Released in 1998 by Monolith Productions, Shogo puts players in the shoes of Sanjuro Makabe, a wise-cracking commander in the United Corporate Authority (UCA). Orphaned at a young age, Sanjuro is emotionally recovering from an accident that led to the death of his brother Toshiro and childhood friends Kura and Baku.

Sanjuro is tasked with taking down Gabriel, the leader of the religiously fanatical Fallen before he can gain control of the planet Cronus and its precious ore, kato, which allows for quick intergalactic travel and the manufacturing of powerful energy-based weapons. The Cronian Mining Consortium (CMC), the governing body which promotes the kato mining business, has complicated matters by declaring martial law on the planet, killing anyone who tries to foil the CMC’s attempts at independence from rival factions including the UCA and Fallen. Sanjuro must fight his way through several dangerous locales that are filled with hostile infantry and mechanized forces from the CMC and the Fallen, both on foot and while riding a Mobile Combat Armor (MCA).

From the outset, Shogo displays many of the characteristics of anime. On booting the game, the player is treated to an anime-style movie sequence, accompanied by a Japanese pop song that was developed from rough drafts received from a Japanese publishing company. The lyrics embody typical anime themes of courage, perseverance and optimism, idiomatically juxtaposed with the over-the-top action shown onscreen.

The audiovisual design is equally noteworthy. Unlike other 3D games released in the late 1990s, Shogo adopts a distinctively anime-inspired art style for its characters, visual effects, and environmental props. The large, bright eyes of the characters, grandiose explosions and in-game mock advertisements are characteristic of the anime aesthetic, as are the cheesy one-liners, hand-wringing angst and cocky humor of the dialog. This is especially apparent in Sanjuro’s conversations with allies like Kura, and foes like Samantha Sternberg, a Fallen soldier who repeatedly assaults Sanjuro throughout the game:

Kura: “Watch my ass!”

Sanjuro: “My pleasure.”

Kura: “You say the sweetest things!”

Samantha: “We meet again!”

Sanjuro: (After defeating Samantha for the third time) “I think you need to get over this obsession; it’s not healthy.”

But Shogo’s anime influences go deeper. Upon close inspection, references to several popular anime series become evident. Some sound effects are strikingly similar to those heard in Gundam Wing and Ghost in the Shell, especially the robot-vehicle transformation and mission log activation sounds. In the second level of the game, the names of certain characters are borrowed wholesale (e.g. Isamu Dyson from Macross Plus, Rick Hunter from Robotech, Noa Izumi from Patlabor). Posters and billboard for ‘CURV’ and ‘War Angel’ directly allude to Neon Genesis Evangelion and Battle Angel Alita respectively. These fan-delighting tributes ooze with Japanophilic character and charm.

In addition to its audiovisual design, Shogo displays strong mecha anime influences in its narrative, which is appropriately chaotic, conspiratorial and convoluted. The plot contains many sudden twists and turns that leave Sanjuro questioning his alliances and objectives as he is caught in a conspiracy that will determine who gains control of Cronus and its resources.

The tone of Shogo leans more towards Gundam and Real Robot than Mazinger Z and Super Robot. The UCA, CMC, and Fallen all have their own legitimate reasons to fight one another, with no faction being unambiguously good or evil. The Fallen and its leader Gabriel, in particular, become less antagonistic in the eyes of the player through a late-game revelation that unveils the Fallen’s raison d’etre: to front the interests of a Cronus native superbeing known as Cothineal. This underground creature is the secret source of kato, and is trying to regain freedoms accidentally stolen from it by the colonizing conglomerates. Its alien nature makes it one of the few Super Robot elements in the game.

Further complications arise from Sanjuro’s commanding officer, Admiral Akkaraju, who gradually becomes irrational in his attempts to eliminate the Fallen, even going as far as to use a kato cannon to obliterate them without taking collateral damage into account. This places Sanjuro in a dilemma: should he stick to his initial orders and eliminate Gabriel, even though the Fallen is trying to help an abused being reclaim its rights from the corporate factions? This moral uncertainty is something that the player must deal with near the end of the game when given the ability to choose one of two paths: either bring Gabriel to justice, or help him seek a truce with the UCA to put a peaceful end to the conflict. The latter option mirrors a situation in Mobile Suit Zeta Gundam, where Amuro Ray and his rival, Char Aznable, set their differences aside to achieve a common goal. As one of the first FPS games to feature a branching storyline, Shogo gives the player the chance to make a morally gray choice and explore its repercussions.

This Real Robot complexity also applies to Sanjuro’s personal relationships with his allies. Much like the Macross series, Shogo features a tangled love triangle that involves Sanjuro, his radio contact Kathryn Akkaraju, and her (presumed dead) sister Kura. The game’s opening monologue summarizes the relationship as ‘kind of complicated’, an understatement of the rivalry between the two Akkaraju sisters which becomes more apparent as the game progresses. More complications arise with the revelation that Sanjuro’s allegedly dead brother and childhood friends are actually still alive. Baku and Toshiro — who turns out to be none other than Gabriel! — had defected to the Fallen, further muddling the distinction between good and evil. Such plot convolutions drive the ambiguous struggles endured by Shogo’s main characters.

All of these audiovisual and narrative elements serve to imbue Shogo with a distinct mecha anime ‘feel’ that balances drama and playfulness, a feat made all the more impressive by the game’s Western origin. But Shogo’s real appeal and biggest nod to the mecha genre lies in the four Mobile Combat Armor (MCA) suits that players can choose from and pilot throughout their adventure.

The roughly 30 feet tall MCAs in Shogo: Mobile Armor Division exhibit many of the visual characteristics synonymous with Japanese mechs, from the humanoid architecture that enables the MCAs to perform elaborate and acrobatic maneuvers to the knight-like armor that adorn their mechanical bodies, a design often shared by the heavy infantry soldiers that the player faces throughout the game.

The four MCAs reflect the aforementioned Japanese philosophy of suggesting recognizable combat classes. They sport different visual designs that reflect their speed and armor stats, such as the Akuma’s ‘scout’ look and the Predator’s intimidating ‘assault’ design. Their naming conventions display an interesting mix of Real and Super Robot elements. On one hand, the MCAs reflect their industrial origin through the name of their manufacturing firm (Shogo Industries, Andra Biomechanics) and classification numbers (Mark VII, Advanced Series 7). Even the term ‘Mobile Combat Armor’ echoes Gundam’s ‘Mobile Suit.’ These militaristic Real Robot motifs emphasize the idea that mankind is the father of the mecha, and that he designed it as a tool used to enhance humanity. On the other hand, two of the MCAs bear Super Robot-style names that refer to malicious supernatural beings: Akuma means ‘evil spirit’ in Japanese, and Ordog is Hungarian for ‘devil’.

The mecha anime influences can also be felt in Shogo’s high-octane gameplay. Unlike most ‘90s mecha video games, which generally consisted of simulators (MechWarrior) and role-playing games (Front Mission), Shogo married its mecha theme with first-person action inspired by id Software’s Doom and Quake. This choice of perspective allows the player to ‘become’ the pilot/MCA, cementing the man-machine bond as they navigate battles filled with visual flourishes typical of mecha anime. These include the trading of shots while closing in and circling hostile mechs, ‘Itano Circus’ missile swarms (named after the animator Ichiro Itano who pioneered the effect in Macross), and massive explosions that fill up the screen. The player’s mech is armed with an array of Real Robot-style conventional and energy-based weapons, ranging from the Pulse Rifle that fires energy balls with high damage, to the Red Riot that causes a powerful nuclear detonation, killing everyone within its blast radius (including the player if they are caught in it). Each firearm offers unique particle effects that serve to further evoke the dramatic combat seen in mecha anime series like Robotech and VOTOMS.

Shogo’s combat is further enhanced by the screams that enemies emit when killed, with some Fallen troops occasionally shouting ‘For Gabriel!’ before collapsing, and the heaps of blood and gore filling the battlefield. These details allow Shogo to solidly capture the cacophony and carnage of mecha anime battles, made all the more exhilarating by the MCAs’ lithe maneuverability. While inside an MCA, Sanjuro is capable of performing virtually all of his on-foot moves including crouching, jumping, strafing, picking up and switching firearms on-the-fly, hovering and even swimming — a far cry from the graceless machines seen in Western mecha works. This allows Shogo’s MCAs to mimic the speed and nimbleness of conventional FPSs like Unreal Tournament and Rise of the Triad in spite of the mechs’ far greater size and mass.

The high level of mechanical maneuverability brings up another important aspect of Japanese mecha design: the notion of the mech as ‘body armor’, intrinsically connected to the human body. While Shogo’s MCAs express mechanical agility and technological prowess, they also display human elements in their design that go beyond their anthropoid architecture. When shooting an enemy MCA, for instance, hostile mechs stagger and recoil as if alive, making the MCA more of an exoskeleton than a bipedal tank by reinforcing the identity of the mech and its pilot. In gameplay terms, this means that the player’s MCA can only withstand so much damage before blowing up and killing Sanjuro, snapping the player back to the reality that the MCAs only thrive due to the existence of their human core. The player is not invincible. Skill is more essential than the mechanical abilities of their mech.

Sanjuro is sometimes accompanied by two friendly MCAs on his missions, recalling the three-unit teams found in mecha series like Special Armored Battalion Dorvack and Metal Armor Dragonar. This archetype reinforces the fact that the player is just another cog in the war effort, despite their character’s high military ranking. Like Amuro Ray from Gundam and Noa Izumi from Patlabor, Sanjuro is not a child prodigy endowed with superhuman abilities or enhanced reflexes. He is just a typical armed participant in a wide conflict. Much of his valor lies in his skillful piloting of his MCAs, reflecting Tomino’s comparison of the pilot-mobile suit relationship with Formula One drivers in that common people rely on machines to achieve a heroic goal. As such, Sanjuro still needs to watch his back while engaging enemy MCAs.

This idea of an even playing field is reflected in Shogo’s critical hit system, which came directly from Japanese role-playing games. Although this system allows the player to occasionally deal more damage than usual and earn a health bonus when scoring critical hits on enemies, the system also grants these abilities to enemies. The player cannot afford to let their guard down, as either side can end a firefight in a matter of seconds by outsmarting the opposition, particularly since Shogo’s battles pit the player against multiple mechs. When one-on-one fights do occur, it is against stronger foes like Baku and Ryo Ishikawa, the game’s antagonist, who closely match Sanjuro’s skills and fill the role of rival pilots, much like Gundam’s Char Aznable and Code Geass’s Suzaku Kururugi. The differences between ‘regular’ and ‘mano a mano’ combat are tied to the player’s level of improvisation and choice of combat approach, much like mecha anime pilots in similar situations, such as the fight between Max and Milia Jenius in Macross. These elements reflect the game’s focus on the ability of the player, and not on the technological capacity of their MCA. As a result, Shogo’s gameplay faithfully models the exhilaration of piloting a fast-moving and powerful mech, as well as the Real Robot repercussions of making poor combat choices that can lead to the player’s defeat.

By transplanting one of Japanese pop culture’s most iconic media forms to the quintessentially Western first-person shooter genre, Shogo gives the player the opportunity to experience firsthand the chaotic action and drama typical of mecha anime, and live out their own power fantasies by ‘becoming’ the pilot/machine and forging their own path through combat experience and narrative decision-making. Through the game’s use of the first-person perspective, the inputs of the player, motions of the robot and emotions of the pilot become one. This seamless mixture of Eastern themes and Western game mechanics makes Shogo a distinctive achievement. It actually feels like an interactive version of an over-the-top mecha series, a testament to Monolith’s strong understanding of the elements that make Japanese mecha unique.

Shogo: Mobile Armor Division is available on GOG.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like