Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

After 3 decades in the industry, Bob Bates explains why he thinks the time is right for Thaumistry his return to text-based interactive fiction. [HINT: vastly improved parsers are part of it.]

Despite being one of the early text adventure designers at the fondly remembered Infocom, having had his name in the credits of more than 45 games over the past 30 years, and being given the Lifetime Achievement Award by the IGDA in 2010, Bob Bates feels the need to re-introduce himself.

“A lot of readers won’t know who I am,” he tells me. Unfortunately, he’s probably right. Bates is mostly known for the adventure games he wrote back in the 1980s and 1990s, like Timequest and Eric the Unready. But then came the rise of 3D graphics, which caused the genre to fall out of commercial favor, forcing Bates to channel his talents into different types of games. But Bates thinks that has changed recently and has decided it’s time for a comeback.

He was encouraged by the crowdfunded success of classic adventure game revivals such as Broken Age, Obduction, and Thimbleweed Park. “I believe the audience for adventure games has always been there, it’s just been economically impractical to reach them,” Bates says. “Today, with crowdfunding and digital distribution, it has once again become possible.”

“I used to spend a lot of my time sitting in the offices of retail buyers, trying to convince them to put our games on their shelves. If I failed, the game would die,” he says. “With a crowdfunded game and no retailers to worry about, I can spend all my time making the game, instead of selling it.”

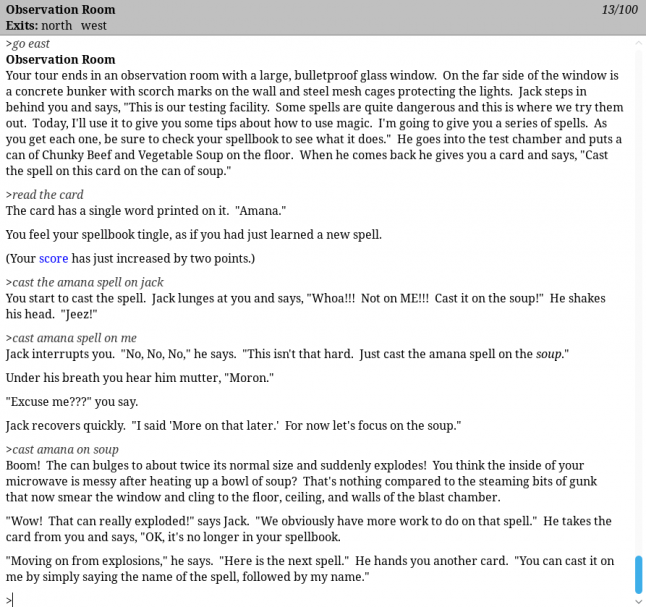

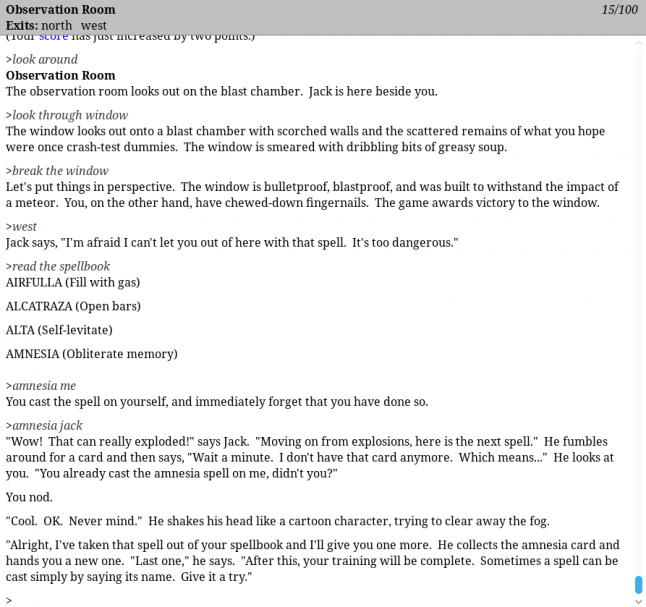

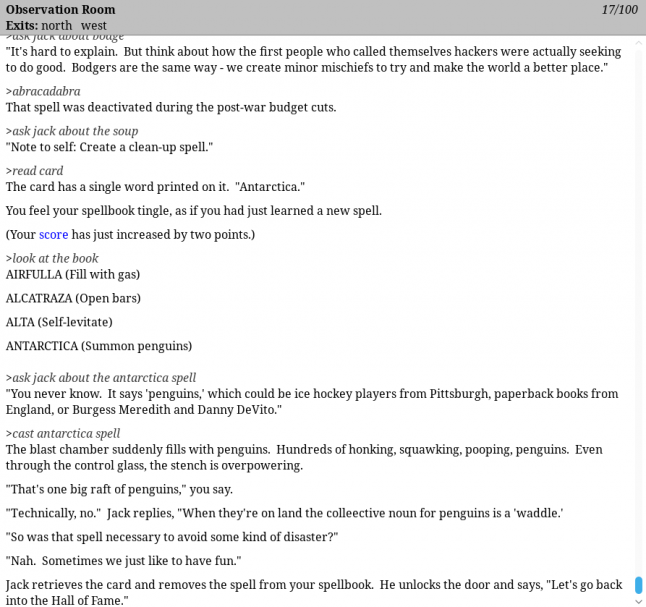

Bates launched his own Kickstarter on January 24th for a comedy text-adventure game called Thaumistry: In Charm’s Way. It follows Eric Knight, a young inventor who is trying to avoid being a one-hit-wonder all his life, while also preventing the exposure of magical people known as Bodgers, especially as he may be one of them.

What may be most striking about Thaumistry is that it has no graphics. It is a pure piece of interactive fiction, or IF.

Thaumistry: In Charm's Way

Thaumistry: In Charm's Way

Bates still prefers the parser-based text adventures made during the heyday of the Z-machine used to make Zork and other Infocom classics, but is hoping to give his a “modern feel.” This is on account of using the TADS engine (written by Mike Roberts and documented by Eric Eve), which allows him to determine the way the game is presented, whether on desktop or mobile.

“One feature [of the TADS engine] I like is that it has an Integrated Development Environment within which you can edit your code, compile, run the game, and debug, all without leaving the program,” Bates says.

"If you wanted to let the player refer to the ‘couch’ as a ‘sofa,’ you might be out of luck. Today, I can include as many synonyms as I want for an object, and even allow for misspellings."

“I like that it is well-documented and comes with several different ways for you to approach learning it. And I like that it is totally user-customizable, which means that I can change any part of the engine that I care to.”

Bates also notes that the TADS engine allows for advances in parsing that will take Thaumistry well beyond the days of >take sword, >kill dragon. He loves that these new, more sophisticated tools avoid the “guess the parser” problem that plagued many older adventure games.

“Some of this is due to the removal of size restrictions. Remember that the first ZIL games had to run in 64K of memory, and even the later ones had only 128K. This severely restricted, for example, the number of synonyms you could have for any given object,” Bates says.

“If you wanted to let the player refer to the ‘couch’ as a ‘sofa,’ you might be out of luck. Today, I can include as many synonyms as I want for an object, and even allow for misspellings.”

The promo video for Bates' Kickstarter feature cameos from adventure game luminaries like Tim Schafer, Steve Meretzky, and Al Lowe.

Improved parsers won't help Bob Bates make his game humorous. One of the tougher promises he has made in his Kickstarter is that Thaumistry will be funny, like his fondly remembered fantasy genre parody Eric The Unready. “I had a blast making that game, and I thought that, even though the market for such a game might be small, it would be very satisfying for me to make, and satisfying for fans of the genre to play,” Bates says.

He has some confidence in how to produce comedy in adventure games. “John Cleese has said that comedy comes not only from jokes, but from the creation of comedic scenes. I had that very much in mind,” Bates says. “Sure, there are lots of jokes, but the trick is to put the player in comedic situations, and let the comedy flow from there."

What Bates loves about parsed-based games is that he has complete control over what he’s building, and can try to get inside players’ heads. He sees his role as designer to anticipate their actions and to acknowledge their most bizarre ideas with a response.

“Most players don’t think an author will have anticipated that crazy action, but if the author does, then a bond is formed between the author and player,” Bates says. It’s in those moments “when players stray from the straight-and-narrow and try weird stuff” that Bates is able to transmit his personality. This is what he seems to treasure most as it allows him a kind of “intimacy” with players that’s rare in games.

Another quality of, specifically, text-only parser games that Bates appreciates is that they don’t cost millions of dollars to make. “Text-only or even point-and-click games are less expensive to create than games with highly sophisticated graphics,” he says. “Uncharted, God of War, and GTA each reportedly cost well north of $30 million to make.”

“When games cost this much, there are fewer publishers capable of funding them, and those publishers become disinclined to take risks. The result is less innovation, and less choice for gamers.”

"As soon as players see an object, they want to interact with it. So, as a designer, suddenly you have to start creating satisfying responses for objects that aren’t necessarily relevant to gameplay."

Bates attributes a lot these staggering expenses to what he calls a “graphics binge” in the game industry. He remembers a time before this, when graphics weren’t the primary assets of a game, when they only required one or two artists. “It is now not uncommon to have between two-thirds and three-quarters of a development staff be artists,” Bates says.

“The result of this cost increase is that games with inferior graphics have a hard time finding an audience, and studios who cannot compete fall by the wayside,” says Bates. He got first-hand experience of this back in the early ‘90s when competing against the likes of Sierra and LucasArts, first at Infocom and then with the company he founded afterwards, Legend Entertainment.

“I really liked the games those companies were making and I rooted for them to be successful, because I wanted the overall market for adventure games to thrive,” Bates says. “I also knew a lot of their authors as friends. But at the same time, they were outselling us by a lot, and that’s always a difficult pill to swallow.”

By going text-only, he is able to create the game almost entirely on his own. He has a few people helping with audio, production, and artwork for Steam thumbnails and trading cards. And he says that he's getting help with coding from the TADS community at intfiction.org, and invaluable feedback from testers. But the core game experience is almost entirely created by Bates.

It’s not just the cost that draws Bates away from the lure of making games with graphics. There are also design issues introduced by graphics that he prefers not to have to deal with. He recalls when he first worked on a game with graphics, the 1989 adventure Arthur: The Quest for Excalibur, which was published by Infocom, and the problems he found at that time.

“As soon as players see an object, they want to interact with it. So, as a designer, suddenly you have to start creating satisfying responses for objects that aren’t necessarily relevant to gameplay,” Bates says.

“Players might want to pick them up, or destroy them, or look behind them, or whatever. It’s very unsatisfying to get a default response like ‘That’s not important’ or ‘You can’t do that.’”

“So suddenly your job as a writer has become much larger, because you want to customize a response that entertains the players, while subtly letting them know that interacting with this object won’t get them anywhere.”

It might be easy to think that Bates is stuck in the past and hasn’t moved on from the 1980s. But his career disproves that. He stayed on at Legend Entertainment even when the company switched over from making adventure games to first-person shooters. “For me, it was hard to see adventure games start to die, but it was also challenging to bring what I knew about storytelling and puzzle design into this very different genre,” Bates says.

In the mid-’90s, he even had the chance to work with the American government to make a series of “serious games,” which he and others at Legend Entertainment thought there could be a big market for.

"There is a level at which game design is the same across all genres. You need to ground players in the gameworld; you need to hold their hand as they start to play, and not overwhelm them; and you need to constantly deliver whatever kind of fun you promised when you enticed them to start playing."

“I designed Quandaries, an ethics training program for the Department of Justice, and that turned out to be an interesting project,” Bates says. “Later, as a consultant, I designed a game to help teach critical thinking to analysts at the CIA,” Bates says.“A big challenge with a serious game is to keep it entertaining while still teaching. The government as a whole is not known for its sense of humor, and navigating those waters is tricky.”

When Legend Entertainment was shut down in 2004, Bates became an independent consultant for game developers, most notably helping to rescue the Spider-Man 3 game to be finished in time for the movie’s release in 2007.

It was during this time that Bates served as the chairperson of the IGDA, first in 2005 and then in 2009. “When I was the Chair of the IGDA, people used to ask me questions about whole categories of games that I knew little about,” says Bates. “I said then, and it’s even more true now, that no one person can wrap their arms around the entire industry and claim to know everything that is going on.”

Bates was hired by Zynga in 2011 to work as the Chief Creative Officer for External Developers, a position that he says was “strikingly similar” to his previous job as a consultant. “I traveled a lot and worked with a lot of different game teams on very different projects, but with each of them my task was to help them understand what their vision was for their own game,” Bates says.

“I often referred to it as ‘introducing people to themselves’. Once we clarified what it was that they wanted to accomplish for their game, I worked with them to clear away the obstacles that were standing in their way.”

“The lesson that emerged from that work is that there is a level at which game design is the same across all genres. You need to ground players in the gameworld so they have a context for what’s going on; you need to hold their hand as they start to play, and not overwhelm them with too much too soon; and you need to constantly deliver whatever kind of fun you promised when you enticed them to start playing.”

He'll have a chance to apply this lesson as he works to complete Thaumistry. The game hit its modest Kickstarter funding goal with a week to spare.

You May Also Like