Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

'This updated 5th edition brings deeper coverage of playcentric design techniques, including setting emotion-focused experience goals and managing the design process to meet them. It includes a host of new diverse perspectives from top industry game designers.'

The following excerpt is from the 5th edition of "Game Design Workshop" by Tracy Fullerton. The book will be published April 19, 2024 by Taylor & Francis, a sister company of Game Developer and Informa Tech. Use our discount code GDTF20 at checkout on Routledge.com to receive a 20% discount on your purchase. Offer is valid through July 4, 2024.

Having a good solid process for developing an idea from the initial ideation process into a playable and satisfying game experience is another key to thinking like a game designer.

The playcentric approach I will illustrate in this book focuses on involving the player in your design process from conception through completion. By that I mean continually keeping the player experience in mind and testing the gameplay with target players through every phase of development.

The sooner you can bring the player into the equation, the better, and the first way to do this is to set “player experience goals.” Player experience goals are just what they sound like: goals that the game designer sets for the type of experience that players will have during the game. These are not features of the game but rather descriptions of the interesting and unique situations in which you hope players will find themselves. For example, “players will have to cooperate to win, but the game will be structured so they can never trust each other,” “players will feel a sense of happiness and playfulness rather than competitiveness,” or “players will have the freedom to pursue the goals of the game in any order they choose.”

Setting player experience goals up front, as a part of your brainstorming process, can also focus your creative process. Notice that these descriptions do not talk about how these experience goals will be implemented in the game. Features will be brainstormed later to meet these goals, and then they will be playtested to see if the player experience goals are being met. At first, though, I advise thinking at a very high level about what is interesting and engaging about your game to players while they are playing and what experiences they will describe to their friends later to communicate the high points of the game. Learning how to set interesting and engaging player experience goals means getting inside the heads of the players, not focusing on the features of the game as you intend to design it. When you’re just beginning to design games, one of the hardest things to do is to see beyond features to the actual game experience the players are having. What are they thinking as they make choices in your game? How are they feeling? Are the choices you’ve offered as rich and interesting as they can be?

Another key component to playcentric design is that ideas should be prototyped and playtested early. I encourage designers to construct a playable version of their idea immediately after brainstorming ideas. By this I mean a physical prototype of the core game mechanics. A physical prototype can use paper and pen or index cards or even be acted out. It is meant to be played by the designer and her friends. The goal is to play and perfect this simplistic model before a single line of code or art asset is ever made. This way, the game designer receives instant feedback on what players think of the game and can see immediately if they are on track to achieve their player experience goals. This might sound like common sense, but in the industry today, much of the testing of the core game mechanics comes later in the pro-duction cycle, which can lead to disappointing results. Because many games are not thoroughly prototyped or tested early on, flaws in the design aren’t identified until late in the process—in some cases, too late to fix. People in the industry now realize that this lack of player feedback means that many games don’t reach their full potential, and the process of developing games is evolving to solve this issue. The work of professional user research experts like Nicole Lazzaro of XEODesign and Dennis Wixon of Microsoft (see their sidebars on pages 299 and 320) is becoming more and more important to game designers and publishers in their attempts to improve game experiences, especially with the new, sometimes inexperienced, game players that are being attracted to platforms like smartphones or tablets. You don’t need to have access to a professional test lab to use the playcentric approach. In Chapter 9, I describe a number of methods you can use on your own to produce useful improvements to your game design. I suggest that you do not begin production without a deep understanding of your player experience goals and your core mechanics. This is critical because when the production process commences, it becomes increasingly difficult to alter the software design. Therefore, the further along the design and prototyping are before the production begins, the greater the likelihood of avoiding costly mistakes. You can ensure that your core design concept is sound before production begins by taking a playcentric approach to the design and development process.

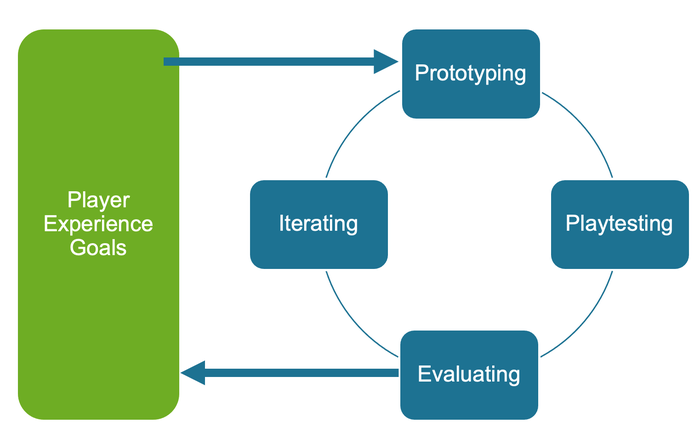

By “iteration” I simply mean that you design, test, and evaluate the results over and over again throughout the development of your game, each time improving upon the gameplay or features, until the player experience meets your criteria. Iteration is deeply important to the playcentric process. Here is a detailed flow of the iterative process that you should go through when designing a game:

•Player experience goals are set.

•An idea or system is conceived.

•An idea or system is prototyped. (This may mean a physical or digital prototype, or even storyboards or an animatic for an idea that can be presented to players.)

•The idea or system is playtested or shown to potential players for response and feedback.

•Results are evaluated against player experience goals.

•Issues are prioritized and addressed by making changes to the prototype.

•The prototype is retested and the results are evaluated against experience goals again.

•This process is repeated until solutions are found and the design is deemed to meet the goals.

As you will see, this process is applicable during every aspect of game design, from initial conception through final quality assurance testing. Figure 1.8 shows how the player experience goals provide a touchstone for the entire iterative process.

Read more about:

Book ExcerptYou May Also Like