Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

For decades, branching conversation systems have been a powerful tool in game narrative. In part one of a series dedicated to the art of branching dialogue writing, we define terms and discuss what kinds of games benefit most from such systems.

This is the first part in a multi-part series on branching conversation systems. See “This Blog Series” (below) for an overview of each part; experienced game writers may wish to skim early posts and jump directly into later segments as they’re added.

Video games are bad at handling conversations. Video games are especially bad at handling interactive conversations. There’s a reason most classic games are remembered for their gameplay or atmosphere rather than their dialogue: talking isn’t a strength of the medium.

But dialogue is a powerful and versatile storytelling tool–it characterizes, it builds relationships, it turns subtext into text, it gives rhythm and pacing to scenes, it creates an “index” of key words and phrases to a narrative, it brings drama into quiet moments… and so on. Foregoing dialogue altogether enormously limits the kinds of stories a video game can tell. So we’ve been using it from almost the beginning, despite our better judgment.

Basic non-interactive dialogue is easy. Screens of text or lines of voiceover are simple to deliver. Yet this approach inevitably turns the Player (the person behind the screen, as opposed to the in-game Player character) into a passive consumer of content.

In many cases, this is sufficient–but interactivity is one of the strengths of the medium. Thus, the dream of a truly reactive conversation, where a Player can engage in a compelling back-and-forth with non-player-characters, approaching them in different ways according to the Player’s whims while still producing witty and dramatic lines appropriate to the situation. We’ve been trying to do this almost from the beginning as well. We’ve come up with new tricks over time, but for the most part, games like Mass Effect and The Walking Dead use systems awfully similar to ones pioneered in the 1980s.

Branching dialogue trees are clumsy, difficult to write and unrealistic. I’m one of the Players who loves them. I’m a writer who loves them. Because they’re the best we’ve got.

When I say “difficult to write,” I mean it. We’ll get into more detail below, but writing for video games in general requires training and skills exclusive to the medium; branching dialogue trees are a medium within a medium, and they require a whole additional skillset to master. You can’t write strong branching dialogue without understanding game narrative, and you can’t understand game narrative without practice and experience. I suspect the number of writers in the game industry who can truly produce great work with dialogue trees is less than several dozen.

I’ve spent a lot of time working with dialogue trees–writing them, editing them, and training junior writers to use them. And like I said, I enjoy games with branching dialogue. I like to see them done well. (I like to see them done at all–they’re a relatively rare breed nowadays.)

Maybe this series will help.

My goal is to walk through both high-level considerations–how to design a branching dialogue system, when to use one and for what kinds of games–as well as techniques for actual dialogue writing. By the time I’m done, hopefully we’ll have a solid introductory manual to this weird, weird art.

At the moment, my plan is to break the series into five parts, as follows:

Part 1: You’re reading it now. We define “branching dialogue,” list reasons to use or not use it in a game, and discuss major pitfalls.

Part 2: The basics of designing a branching dialogue system, from interface to the choice of voiceover vs. text to integration of non-conversational game mechanics.

Part 3: Fundamentals of structure–how to build a dialogue tree that’s easy to understand and easy to maintain.

Part 4: High-level principles of branching dialogue writing. e.g., keeping scenes Player-focused, making choices “matter,” and handling Players disinterested in narrative.

Part 5: Tips for handling branching dialogue on a line-by-line level–differentiating Player responses, maintaining voiceover flow across branches, etc.

I encourage readers to post questions and comments here or e-mail me directly at alexanderfreed.com. If there’s enough dense discussion material, I may add a sixth part to cover new topics.

One thing I won’t cover is dialogue writing tips that generally hold true across multiple media. Differentiating character voices, keeping a scene moving briskly, writing for actors vs. writing for the page… these are important topics, but they’re covered in hundreds of other “how to” guides for fiction writing. Our focus is exclusively on interactive media.

What do I mean when I refer to a “branching conversation” or “branching dialogue tree”? I mean a system where a Player character and one or more non-player characters engage in a simulated conversation in which:

a) The NPC says something.

b) The Player is presented with a limited set of options indicating ways to respond.

c) If the Player’s chosen response is not a literal line of dialogue (e.g., if the Player selects from a set of symbols), the literal result is displayed after the response is chosen. If the response options displayed are lines of dialogue already, we can skip this step.

d) The NPC replies according to the Player’s chosen response. (The conversation “branches” according to the Player’s decision.)

e) The Player is presented with a new set of response options distinct from the previous set. (Response options may be repeated in certain cases.)

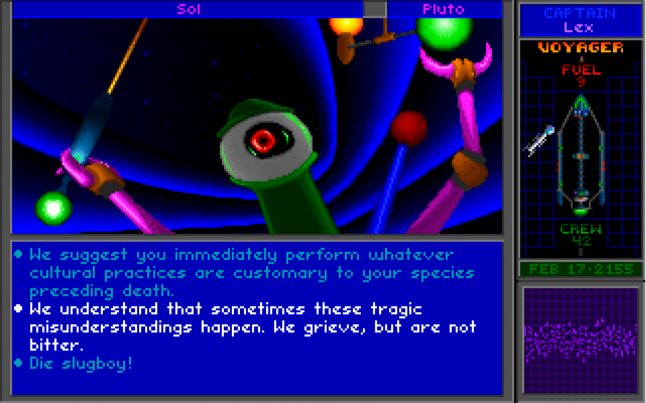

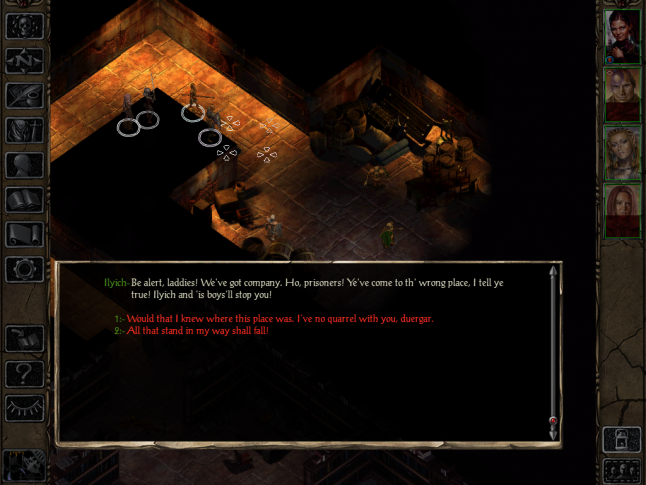

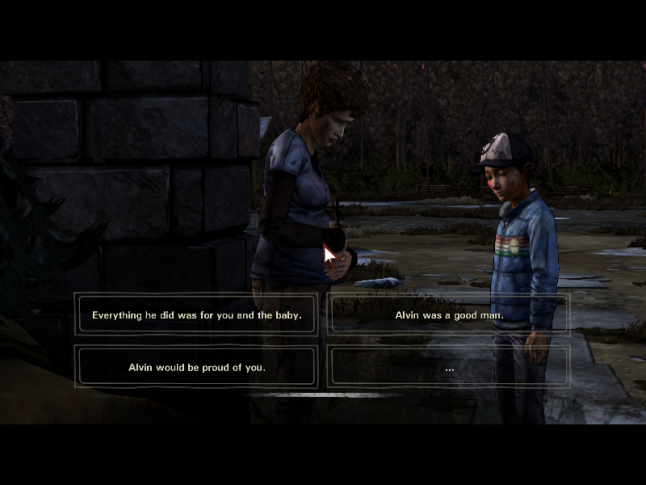

There are many variations and different levels of complexity that can be involved, but that’s the core loop that defines a branching dialogue tree. While a proper history is outside the scope of this post (maybe another time–and if you’ve got examples of more pre-1990 games with conversation trees, please get in touch or post in the comments!), a few games that use such a system include:

Space Rogue, Origin Systems, 1989

The Secret of Monkey Island, Lucasfilm Games, 1990

Star Control 2, Toys for Bob, 1992

Wing Commander III, Origin Systems, 1994

Fallout, Interplay Entertainment, 1997

The Longest Journey, Funcom, 1999

Deus Ex, Ion Storm, 2000

Knights of the Old Republic, BioWare, 2003

The Witcher, CD Projekt RED, 2007

Alpha Protocol, Obsidian Entertainment, 2010

The Walking Dead, Telltale Games, 2012

The Banner Saga, Stoic, 2014

These games tend to be categorized as role-playing games or adventure games, or at least action or strategy games with RPG “elements” (Wing Commander III, generally considered a “pure” space combat game, is the major exception on this list). Note that many of these games were critically acclaimed at the time of publication and remain fondly remembered for their narrative. Games with conversation trees have staying power.

What sorts of games and game narratives benefit from using a branching dialogue system? Generally speaking, branching dialogue trees benefit:

Character Emphasis. Any dialogue-heavy game allows the opportunity for extensive character development, of course, but interactive dialogue increases a Player’s engagement with the text; it forces a Player to think deeply about NPC interaction and makes understanding NPC and Player character personalities a part of gameplay.

Player Character Customization. By allowing a Player character to speak according to the Player’s choices, a branching dialogue system allows unparalled agency and ownership of Player characters by Players. Players tend to feel more attached to and interested in the game’s protagonist.

Branching Narratives. Branching dialogue allows for a clear and simple means of branching a game’s overall storyline. If you’ve already decided to use a branching narrative, adding branching dialogue is a logical next step. (The same is true in reverse, as well.)

Complex Storylines. By focusing the Player’s attention and putting the Player in charge of learning about the setting and interrogating NPCs, a branching dialogue system supports complex, detail-driven plotlines. Uncovering the storyline becomes part of the gameplay rather than simply the result of gameplay, and the Player can absorb new information at her own pace. (This is, of course, the classic argument for hands-on learning over classroom lectures.)

On the other hand, there are some games where a branching dialogue system is a poor fit. Generally speaking, branching dialogue trees don’t match with:

Predefined Player Characters. Does the Player character have a clearly and narrowly defined personality? Is the Player character intended to experience a specific emotional arc (e.g., a redemption story)? Branching dialogue puts enormous control in the hands of the Player to define the protagonist, and while Player options can be limited under a branching dialogue system (it’s possible to create a game with branching dialogue in which, in all branches, the Player is funny or patriotic or what-have-you) the options can’t be nonexistent.

Some traditional, puzzle-oriented adventure games allow no Player control of the Player character’s “inner life” or personality while still using branching dialogue; in these cases, the branching dialogue is typically focused on puzzle-solving and information-gathering rather than character development. Branching dialogue trees as puzzles is something I won’t discuss much in this series, but the approach is worth remembering.

Predefined Storyline and Quests. If a Player’s dialogue choices have no impact on the larger storyline and gameplay sequences outside of conversation, the result may be a letdown. Branching dialogue is best matched with a narrative that supports multiple stories and outcomes.

Pure Gameplay Focus. While branching conversation sequences don’t need to be lengthy and can match fast-paced gameplay, they can distract a Player from the flow of other elements. Branching dialogue might add narrative interest to Tetris, but it would probably detract from the overall feel.

Suppose your game is a strong match for a branching conversation system. There are still a number of factors to consider before proceeding.

High Level of Skill Required. As previously emphasized, branching dialogue is very difficult to write well. If your team isn’t familiar with the medium, you may run into a number of unexpected problems and end up with a suboptimal result.

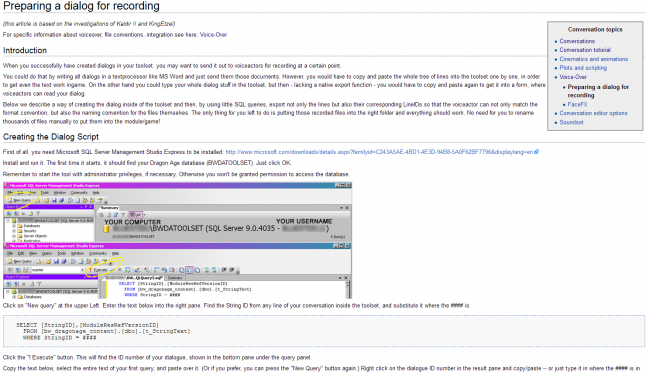

Tool Requirements. Good branching dialogue requires a dedicated tool to write and additional tools for implementation by audio, cinematics, and other departments. Microsoft Word or Excel won’t cut it. A few commercial toolsets are available but may not be appropriate for your needs. Be sure you have adequate programming support! We’ll talk a little more about available and example tools in a later post.

Expense. Aside from tool programming and writing costs, consider the additional expense of implementing branches (whether done by a writer, programmer, or scripter), testing branching content, and any voiceover costs. Cinematics can become substantially more time-consuming to develop. Analyze the expense of branching dialogue to every department before moving forward.

While there are far too many potential alternative conversation systems to list here, a few common ones follow.

Non-Interactive Dialogue. Pure non-interactive dialogue–conveyed through text, cutscenes and voiceover, or another means–is implemented in most modern games. As a system, it’s unspectacular, and still requires a thorough understanding of techniques unique to game narrative. It can nonetheless be engaging and entertaining when used correctly.

Simple Choice. Rather than full branching dialogue trees, games that offer a “simple choice” present multiple options for how to approach a conversation upfront (e.g., “Threaten” or “Diplomacy”), then show the result. This type of dialogue is often seen in strategy games or role-playing games without much emphasis on story. It allows a degree of Player control and works well for scenarios where the entire conversation doesn’t need to be heard or shown word-for-word (allowing the conversation to be summed up in narration).

Simple Hub. A simple conversation hub allows a Player to choose from a list of topics (often questions) and provides a different NPC response to each. However, the conversation does not branch or present “layers” of additional responses–often, the optimal way for a Player to use a simple hub is to choose each topic in sequence until every one has been exhausted. Depending on how new topics are added (through interactions with other NPCs, entering topics manually via keyboard), a simple hub can give the Player a sense of thoroughly investigating a subject or a mystery.

We talk about designing your branching dialogue system and what’s appropriate for your game. Topics will include voiceover, interface, and “waterfalls” vs. “hubs.” (If you’re eager to get to the nitty-gritty of dialogue writing, all I can do is urge patience. We’ll get there…)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like