Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"We were overwhelmed by this desire for everything to be interactive. It took us maybe a whole year to understand how we could shape the game in a way that that no longer was a problem."

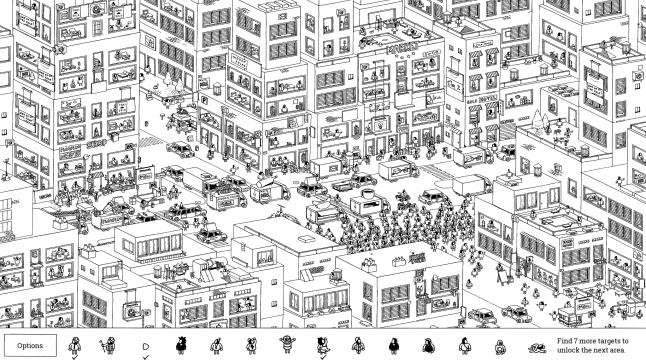

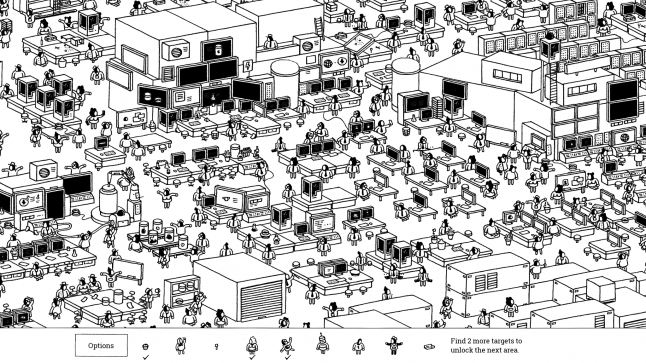

Visual puzzle game Hidden Folks has been compared to the Where’s Waldo? books a number of times since it came out in February for Steam and iOS. It makes sense: both task you with scanning large 2D scenes crowded with people to find a hidden target. But the comparison fails to acknowledge how much design work was required to take the Where’s Waldo? format and turn it into a compelling video game.

Hidden Folks is the first game Adriaan de Jongh has designed since the studio he co-founded with fellow Dutchman Bojan Endrovski disbanded in 2015. The studio, called Game Oven, allowed de Jongh to think about the thousands of social interactions we perform every day, and then design a game around one of them. The results were games that played unlike any before them, such as the awkward intimacy of finger-based co-op game Fingle, and the ballet-inspired dancing of two-player game Bounden.

At the time Game Oven was closing down, de Jongh wrote that it was due to the team being “at a point where we are in need of another vision for a beautiful game, but where we don’t have one, and don’t have the financial resources to find one and make one.” At around the same time, de Jongh stumbled upon the graduation exhibition of French illustrator Sylvain Tegroeg, sending him on the path towards making Hidden Folks.

Tegroeg’s exhibit was a series of objects contained in glass globes called “Idea Globes.” But what de Jongh found himself staring at were the black-and-white drawings hanging behind the globes, in which he saw “worlds of tiny people doing everything and nothing at the same time, yet many little stories unfolding.” It gave de Jongh an idea that prompted him to jokingly tell Tegroeg that they should make a game together.

Tegroeg's "Idea Globes"

“We exchanged business cards, I checked out his website, thought ‘heck, let's give it a try’, stole some of his artwork from his website to make a prototype, emailed him and met up soon after that,” de Jongh says. “We were both surprised how cute the prototype was, and decided to put a bit more time into it together just to see where it would end up.” As it turns out, the pair spent the next two-and-a-half years expanding that prototype and tackling the unexpected challenges that came with it.

The most obvious difference between Where’s Waldo? and Hidden Folks is that one is a static drawing on paper and the other is interactive. What interaction introduces to the format that de Jongh and Tegroeg had to tackle is player expectation. “If we made one thing interactive, players almost automatically expected other things to be interactive as well,” says de Jongh.

This was an issue as Tegroeg was able to draw things much more quickly than de Jongh could program interactions for them, so making everything interactive would take far too long. A careful balance was needed.

“Every object we made interactive added an expectation to similar objects in the game, and making too many objects interactive would create the impression that everything was going to be interactive,” de Jongh says.

“An example of this player expectation would be the doors in the game: we started out making one openable door, but concluded from playtests that that one door created the expectation that all other door-like objects would also be openable.”

“Especially in the early stages of the game's development, we were overwhelmed by this desire of the player for everything to be interactive,” de Jongh says. “It took us maybe a whole year to understand how we could shape the game in a way that that no longer was a problem.”

The pair came up with two solutions. One was to add small, tutorial areas in between the bigger levels to teach players the basic interactions of each environment. In the introductory level to the city, for example, players learn that they can rotate satellite dishes, break bricks in certain types of wall, as well as pull garage doors up. Establishing this visual language with players sets their expectations and helps to eliminate frustration they might experience going in without that knowledge.

The other solution to player desire for interaction was to add sounds to absolutely everything. While that might still be a lot of work it’s nowhere near as much as animating everything. Plus, the sounds in Hidden Folks are entirely a cappella, meaning that creating them is cheap and easy.

“The first time I used my voice to add sounds to anything were some experimental videos my girlfriend had made,” says de Jongh. “The videos featured solely inanimate objects, and I added my voice to them in a way that gave them character. It was tremendously silly, but we laughed really hard at it and did it again with a few other videos later.”

De Jongh repeated the trick during a Global Game Jam and it ended up winning his team the Best Audio Award that year. “This was around the time Sylvain and I started adding more basic features to the game, and I borrowed some of the sounds I had recorded in that game jam for Hidden Folks,” says de Jongh. “I thought it was kind of funny. Sylvain thought so too, and we decided to stick to it.”

While making sound effects with his mouth proved economic, de Jongh also thinks of them as one of the two big sources of character and comedy in Hidden Folks. The clues that help players to locate each target within levels is the other source. Many of the clues contain jokes as they were made during collaboration: either while Tegroeg and de Jongh were designing the game’s world, or across the two evenings de Jongh spent with his friend Bram van Dijk having fun and writing clues.

“It would become obvious during playtests whether the jokes worked or not, and we rewrote the ones that didn't work or removed those targets entirely,” de Jongh says. “The lesson I learned from making many of the jokes in the game is that other people are way more funny than I am. Thank god for playtesters making this painfully obvious sometimes.”

The clues in Hidden Folks come in the form of written sentences that appear at the bottom of the screen when players click on one of the targets they’re after. They were considered necessary as the game’s illustrations are black-and-white, and therefore don’t have the luxury of color to help players scan the dense images. The main visual tool Tegroeg had to guide the player’s eye was contrast.

“The amount of blackness really determined how hard it was to distinguish the areas and objects. Think about thicker grass or the occasional denser pattern,” de Jongh says. “We often thought about diversifying how much contrast there was around the targets hiding in plain sight so that those had different levels of difficulty. Contrast also occasionally helps guiding people's eyes in distinguishing interactions with non-interactions, but this wasn't something we wanted to exaggerate as it would make discovering the interactions boring.”

De Jongh adds that the clues do more than deliver jokes and help players find their targets. He considers their third function to be one of the fundamental differences between Where’s Waldo? and Hidden Folks. “In Where's Waldo? you’re looking for specific graphics, whereas in Hidden Folks you are looking for a story,” de Jongh says. “On top of that, many of the targets in Hidden Folks aren't hidden in plain sight but require an interaction with the environment to become visible, and this adds depth to the stories of the targets as you as the player can be the driving force behind that story.”

What de Jongh is referring to is how the clues are designed to have a conversation with the game’s world. For example, one clue reads, “Salma has been waiting for more than two and a half hours to cross the street. Can’t the bus drivers see this is a pedestrian crossing?!” With that clue, players can search for a woman standing at a pedestrian crossing, but it’s not enough to find her, as they also have to click on a bus to make it stop at the crossing so she can get across the road - only at that point can players complete that target.

“Some clues would point at entire areas on the map, while other clues talk about specific objects that we would then make sure to be carefully placed somewhere on the map that would make sense to people,” says de Jongh. “We distilled a list of things to consider when adding new targets and hints, and tried to represent the different kinds of targets and hints throughout the game.”

Here is that list, courtesy of de Jongh, who adds that “there's probably more things we thought about but never bothered writing down”:

Targets:

target hidden in plain sight

target hidden behind a known interaction

target hidden behind an unknown interaction

target hidden behind a puzzle of interactions

target being very small

target hidden by having a different animation

target hidden by being the only one holding a specific object

target hidden by being in a different context

target hidden by timing

target hidden by bad contrast

target revealed by a sound

Hints:

hint pointing to one specific location

hint pointing to a small area

hint pointing to a large area

hint pointing to objects that are everywhere

hint pointing to a particular indicator

Out of the items in that list, the one that isn’t seen much of inside the final version of Hidden Folks is “target hidden behind a puzzle of interactions.” There are reasons for this. “We found out pretty early on in development that multi-interaction targets were extremely difficult for us to make [and to make visually indicative], and because of that super difficult for players to understand,” de Jongh says. For that reason many of them were abandoned.

Another type of challenge that was dropped from the final game is timed challenges. “The idea of those areas was that the camera was fixed to a walking character or a driving car, and you had to find things before they had passed by,” de Jongh says. “However, we decided to throw them all out just before the v1.0 build because it was simply too frustrating for most players having to replay the area twice or three times to find everything. We thought it would be a nice change of pace, but the areas just weren't as fun.”

However, one of these timed challenges has survived, and can be found in the third area of the game. You have to help a walking folk across treetops by moving objects out of the way. The previous version of this level let players fail but now the character simply stops in their path and waits for the player to clear the way if they’re not quick enough.

This version of the timed challenge fits in with the philosophy that drives all of de Jongh’s games and therefore Hidden Folks too. It’s a kind of folksy playfulness derived from physical games and the larger tradition of folk games. Those tougher challenges in Hidden Folks don’t play into that approach, hence they had to go. “Playfulness manifests in Hidden Folks by allowing you as a player to take your time and to tap everything with no penalty,” de Jongh says.

That philosophy is why Hidden Folks is a game that forgoes challenge so that players can find pleasure in searching canvases and making small discoveries. The few design elements it has are the result of rigorous playtesting and working towards a vision of a game that is as lighthearted as blowing a raspberry.

That said, de Jongh says that the new areas he’s currently making for Hidden Folks will shake it all up: “We plan to make more puzzle-like areas where you're not looking for targets but rather have to 'solve' the entire area.” The new levels will be larger and more complicated than anything seen in the game so far. His challenge now is to make sure Tegroeg’s illustrations remain sources of joy rather than exhaustion.

You May Also Like