Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Road to the IGF: SmallLife explores an interactive city base on Shenzen, China, hiding playful puzzles as players wander a slice out of everyday life here.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series.

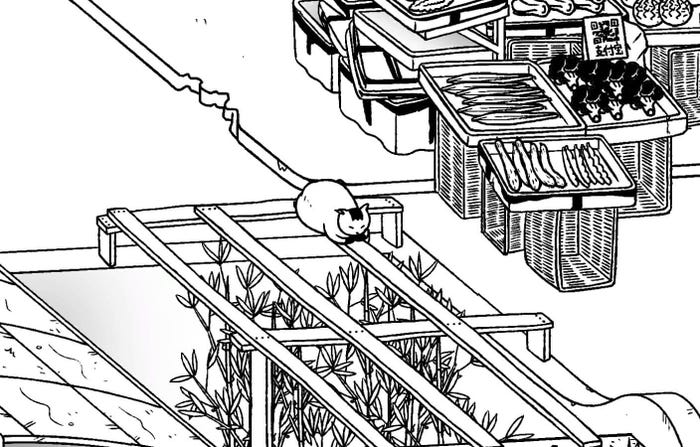

SmallLife explores an interactive city base on Shenzen, China, hiding playful puzzles as players wander a slice out of everyday life here.

Game Developer sat down with Yueqi Wu, developer of the IGF Best Student Game-nominated title, about exploring the conflict between the "city" and "human vitality" in their work, about how they captured real-world details to bring the in-game scenes alive, and the importance of capturing the unique atmosphere and people of southern China for the project.

Game Developer: Who are you, and what was your role in developing SmallLife?

Yueqi Wu: I am Yueqi Wu, the creator of SmallLife. This project was my graduation project from the Department of Animation at Tokyo University of the Arts Graduate School of Film and New Media. In the animation department, we usually focus on individual project making, creating one project each year over the course of two semesters. SmallLife was my second year project, and I also created a small interactive game during the first semester (with the help of a programmer).

I began creating works in the form of animation, comics, and picture books about ten years ago. I enjoyed observing human actions and recording them, while at the same time thinking about what made them interesting and meaningful. This is the motivation and passion in my daily life. Usually, I start with asking questions before making a new project. For example, why do people act in this particular way or why should things be the way they are?

We face a lot of “WHYs” every day. While scientists will answer these questions with science, as artists we answer with art. I used to work for a video art organization called Video Bureau in Beijing. During that time, I had the opportunity to become acquainted with many video art works and artists. Each one revealed subtle and sensitive observations and experiences about the world. Sometimes when I look at a piece of art, it feels like my brain has been struck by a meteorite. It has really opened up the way I think about my own work.

The interactivity and wide-ranging possibilities of video games is deeply appealing to me, so I decided to participate in the game course in our Department of Animations and try to make some video game projects.

What's your background in making games?

Wu: My game production experience mainly comes from the game company I spent three years working for. During that time, our company used the cocos2D series to make games. In addition, based on the games that I had played, I also knew a bit about the production process of game-making. As a student, I benefited greatly from the game courses at our university and from the cooperative project with USC, which gave me a more systematic understanding of game production, such as the process of prototyping and vertical slice making. It was very useful for helping students quickly get started with the basics of making games.

I hope players who play or watch SmallLife can feel a relation to their own city and think about all of the people around them who are experiencing different lives every day.

The biggest difference between game production and my previous animation work is that games have a gameplay mechanism, but I think the core of creation is the same, including the purpose and the goal. No matter what form of work it is, there is always a core that the creator wants to express. When the purpose of the content we convey is clear, the audience and players can understand the story the work wants to tell. This allows it to achieve a connection between the audience and the creators. This is the reason why I switched from animation to game making.

I have found this to be a very interesting direction, and have also really felt the joy of game creation while making SmallLife.

How did you come up with the concept for SmallLife?

Wu: Because of my interest in portraying human nature, most of my works are narratives featuring people and relationships. Some are based on stories about myself and friends, and some are entirely fictional. While creating these narrative projects, I gradually discovered that one of the reasons that people fascinate me so much is because I like finding the connection between a behavior and its trigger. It is somewhat similar to the idea of karma in Buddhism.

SmallLife is also an attempt at revealing truths about people. In the past, I made short animation films describing the stories of people living in small communities. This time, I wanted to set my work in a larger location and explore a new theme: How to let people living in a rapidly-developing city discover their own vitality and enjoy life. I will expand on this theme when I update the game in the future, and will also generate some new ideas or create entirely different works based on this concept.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Wu: The art in SmallLife was all drawn with Photoshop, including city buildings, UI, and character animations. My classmates typically use TVP to draw frame-by-frame animations, but I've been using Photoshop's timeline to draw frame-by-frame animations for a long time, so I decided to continue using it. The game-making and programming was done in Unity. A friend of mine served as my tech support, helping me with the programming aspect.

What interested you about capturing the small moments in life in a game? The moments of life in Shenzhen, China, specifically?

Wu: The contradiction between people and cities is usually more pronounced in big cities. This is what I really felt when I lived there. The development of a city requires financial support, and although the quality of our life has improved, the vitality of humans has declined.

In addition, I think in young cities like Shenzhen, where they are relentless in the pursuit of technological innovation and urbanization, the people seem very small, as if they have less substance.

I attempted to use the mechanics of puzzle games to allow players to experience interesting changes in people's lives in the city. These interesting changes are expressions of my hopes to give people a new perspective on their everyday lives and prompt fresh vigor. I have always been interested in the conflict between "city" and "human vitality" and I wanted to make players feel this contradiction through the game.

How did you decide on the people, places, and events to put in the game? What things did you decide to put in that made this feel like a real, living place?

Wu: In the current version of SmallLife, all three stages exist in real life. My ideal vision of the stages include markets, train stations, subway entrances, and even the narrow spaces between two buildings, all of which have the possibility to be depicted. The current stages: Longhua Park, Huaqiangbei, and Baishizhou are some of the places with distinctive features. Longhua Park is a place where migrant workers often live. Huaqiangbei has a dense flow of people transporting goods, and Baishizhou is a big village located in the center of Shenzhen that is about to be demolished. There are many residents who come to Shenzhen to work. All of these great places have already become an encyclopedia containing thousands of possibilities to observe humans that are rich in material for us to think about.

I feel that real life is sometimes where the most vivid and dramatic conflicts take place. The actual feelings associated with my own conflicts were a particularly important aspect while making this game. I described a lot of moments I encountered in real life. For example, in the Huaqiangbei electronic market stage, the person who extinguished the cigarette butt beside the stone pillar. Generally speaking, there are many ways to snuff out cigarette butts. Most people throw them on the ground and step on them, toss them in the ashtray above the trash can, or just leave them in the corner of the wall. But this man's posture is most appropriate to snuff out the cigarette butts on the side of the stone pillar he is stepping on. These types of movements make the game very realistic because they come from the details of our own life.

What thoughts go into turning everyday life into puzzles? Into making delightful puzzles that are hidden in this ordinary world?

Wu: In SmallLife, the key to solving puzzles and finding the goal item is clicking two places to trigger an event. This requires some imagination, because in this game, I try to do some experiments on constructing “vitality”. If someone who never knew how to draw becomes an artist, they have experienced the process of the rebirth of “vitality”. Then, maybe we can say there are probably many things that can become vitality. For example, in stage two, the light refracted from the mirror in the second-floor apartment burned the mouse on the first floor. Or, in stage three, there are two men who are wearing the same underwear and become friends. The puzzles are weird, but there is some logic to them.

I always think there are some questions that should be answered with creative thinking in order to make us more energetic. Although the world has rules, we can also create our own rules. This is the idea my puzzles bring to the audience.

Although the puzzles seem simple and disconnected, I have racked my brain for each one. At the same time, I'm still trying to come up with examples that better fit the absolutely excellent description of "vitality" in my heart.

What drew you to the art style for the game? What made it feel right for SmallLife?

Wu: I had a few references towards the beginning of the project. One is the picture books I liked when I was a child called "Where's Wally?". A second was my daily routine of observing others while outside. The connection of these two points indicated to me that I should make a city discovery game. Another influence was the game I played a few years ago called Hidden Folks, which is also a game of finding items. I was attracted by its rich urban design through simple art styles, so I used the same top-down angle and black and white lines to design the scene when I first conceived the project.

The unique atmosphere of southern China is also important. In order to reflect the behaviors of characters that are more in line with reality, it is necessary to refer to real people in real life. Their dynamics and states can reveal what the character might be doing in each stage. What they are actually doing, and how they live.

What do you think interests players about exploring the world of SmallLife? What makes them want to look closer at this snapshot of life?

Wu: There is a very real reality depicted in SmallLife. We usually create games that are fictional because games represent virtual worlds. Although I didn't mention it in the game intro, this is the actual environment. When players open the game, they should be able to realize that this is a real "life" world that is close to each of us.

During my studies at the university, I once watched a project of a student who came from the Department of Media Art. He implanted Google Maps into his project and added two selectable characters in the game. Players could connect with another player to communicate their current real position and be keyboard operation protagonists while finding each other. Through the process, every time you turn a street corner, you can see people passing by, or dogs, and maybe you can see familiar things and places.

The most interesting part about this work, for me, is that you can build a little virtual idea in real life. I am fascinated by this kind of creation that is extended on the basis of reality. I think it is also the place where players can experience the most.

What do you hope to make the player feel as they explore this world? As they look closer at the ordinary lives here?

Wu: I hope players who play or watch SmallLife can feel a relation to their own city and think about all of the people around them who are experiencing different lives every day. Happiness, troubles, and so on. It is possible that when you obtain objects through some trigger, you may be able to associate them with the things you have encountered in your life, which may change due to your behaviors. And they might even give you new "vitality".

In addition, most of the characters appearing in the game are blue-collar or unemployed. Some of them are on the fringes of society, and some rely on work to make a living every day. Because I think that most people do not have extraordinary talents, the vast majority of "us" actually live like this every day, repeating our work, day in and day out, and rarely have the opportunity to think about our own life or the ability to gain more creative opportunities.

But even that doesn't stop people from thinking about what “vitality” is. I hope that one day in the future, everyone in the world will be able to live the life they want to live with vitality every day. This is what I thought about the most while creating SmallLife.

This game, an IGF 2022 finalist, is featured as part of the IGF Awards ceremony, taking place at the Game Developers Conference on Wednesday, March 23 (with a simultaneous broadcast on GDC Twitch).

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2022You May Also Like