Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The developer talks with us about the challenges of making a game that can fuse any two creatures.

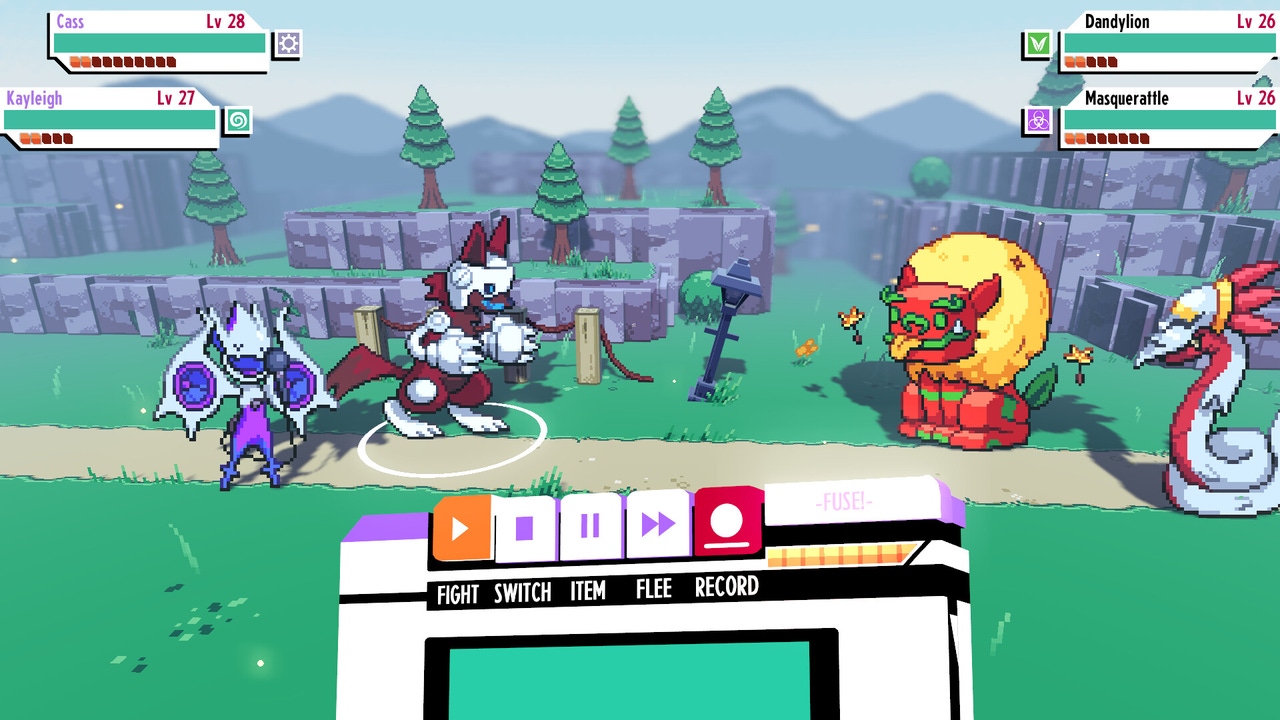

Cassette Beasts sees players going out on a monster-collecting adventure, recording creatures onto tapes to use in battle. Players can combine any of these creatures together to form something different, too, offering near-endless possibilities for your team.

Game Developer sat down with Jay Baylis, director at Bytten Studio, to talk about the challenges that came from creating a monster-fusing system that could combine any creatures in the game, what appealed to them about creating a more humane means of "capturing" monsters, and the appeal of letting the player create and use "unbalanced" monster fusions if they made the game more fun and interesting.

Cassette Beasts combines mix tapes and monsters. What inspired this particular concoction?

Cassettes are cool and old-school, but kind of timeless! When it comes to franchises that involve regular human characters summoning/commanding/manifesting fantastical monsters to battle (whether that be Pokemon, Digimon, YuGiOh, etc.) there’s always a physical element that connects the fantastical and mundane. Whether that thing is capsules, playing cards, or something else, the fantasy is best sold when you can imagine holding something in your hand that bridges the fantasy. Cassette tapes are mundane items that are kind of old school and rooted in a pre-digital era—they’re kind of perfect.

The game offers a complex monster-combining system that lets players combine any monsters together. What drew you to put in this system?

We knew that if we were attempting to establish a new game in the monster-collecting RPG genre, then we needed to have a unique angle that no other game would have. Fusion is something we kept coming back to—it is something very popular among fandoms of games in this genre, but it’s also very difficult to design in a game. Tom Coxon and I have worked with procedural generation systems for creatures in games before, so we were pretty confident we could make this work! Once we started testing out fusion designs and finding ourselves surprised and entertained by the end results, we knew we were on to something.

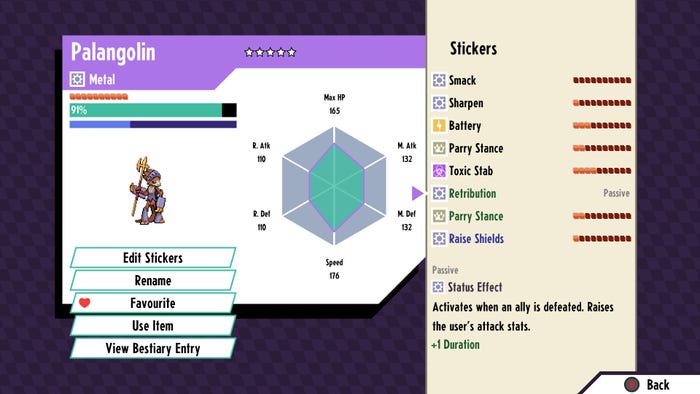

Can you tell us a bit about how the system works? How did you design something that could handle combining any monster with any other creature to make something coherent, visually as well as gameplay-wise?

It’s deceptively simple. Essentially, every monster is designed twice: once as a bespoke animated character, and a second time as a modular character sprite with separate parts. The fusion system simply mixes up elements of this latter version.

What difficulties came out of putting this system together? Can you tell us how you overcame them?

The real difficulty came from me having to animate a whole bunch of "fusion parts"—animated sprites for heads, legs, arms, tails, and so on. There are hundreds and hundreds of these parts, and when I was in the middle of them it really could feel like an endless task to keep producing them.

Did this system affect how you designed the individual creatures? How so?

One minor restriction is that since monsters all need to have similar-shaped heads when fused, I’d find myself often leaning towards designing monsters with round heads. Otherwise, though, I didn’t find myself restricted.

Can you walk us through how you came up with some of the monster designs?

I had to design nearly 120 monsters myself (except for a few guest artists we brought on) so there was a lot to design in a relatively short amount of time. I would do a lot of sketches and run them by Tom and the team for feedback. A lot of monsters received a first draft design before making it, whereas others took a lot of revisions. I feel like this was a big task, but one I’ve been preparing for my whole life.

The cassette tapes make for a humane means of "capturing" monsters. What interested you in using cassettes? About finding a way to keep monsters without imprisoning them?

We wanted to create a game with a bit more grown-up worldbuilding than games we’d made before, so we really wanted to avoid "family-friendly cockfighting" as a concept for our monster-collecting game from early on. "Transforming into monsters" soon rose as a concept that we really liked, and finally "recording monsters using cassette tapes" gave us a great explanation for how you can capture monsters without enslaving them. You aren’t really capturing them—you’re copying their data to a tape!

What thoughts went into the game's combat system? What did you do with your battle system to make it feel unique?

We really wanted to create a battle system that lent itself well to experimenting and multiple levels of strategy, which is how we ended up with our "chemistry system". Different combinations of elemental attacks lead to different status effects inflicted, meaning there's a lot to discover. However, the game can be enjoyed without memorizing all these combinations so there isn't too much pressure to master the systems!

How did the ability to fuse monsters and their abilities inform the battle system?

Since two monsters can have two different elemental types, a fused monster will almost always have two elemental types—something that doesn't occur on monsters otherwise. Not only that, but their stats being added together makes a fusion form very powerful! For this reason, we decided to treat fusion forms as a mid-battle power-up—something akin to a super move. We want it to be climactic and exciting every time players fuse.

Did the ability to fuse anything together make things unbalanced at any point in development? What did you do about this, and why?

We decided to encourage players to seek builds that are "unbalanced"—we think there is a lot of fun for players in discovering strategies that are unexpectedly overpowered or make the game significantly easier. If the players are engaged and having fun, we think that's a positive result.

What drew you to add a co-op element to the game? What challenges or neat elements/surprises did this create in its design?

We’re big fans of local co-op games, and our previous game, Lenna’s Inception, featured a similar implementation. We thought the gains of implementing it would justify the extra development complexities, as we figured players would appreciate its inclusion as much as we feel we do when we play games.

What challenges came out of implementing co-op play into the combat and exploration? How did they affect the design of the battle systems and the world they would explore?

The co-op doesn't affect combat in a significant way, as a second player controls the second party member that player one normally controls. However, in the world, the second player is able to interact with things in the same way as the player in a single-player session. This means twice as many opportunities to carry objects to create shortcuts! You can indeed use local co-op in the game to progress quicker in certain areas and with certain puzzles, but we think that this is still fun, so we ultimately don't mind!

Did the design of your previous game, Lenna’s Inception, have any effect on the creation of this game? Any lessons you learned that affected how you designed Cassette Beasts?

Lenna’s Inception taught us that you can make a game that mixes the bright and colorful with a creepypasta darkness and a kind of punk rock vibe. There’s a lot of its DNA in Cassette Beasts, although Cassette Beasts is a much more friendly game.

You May Also Like