Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How to approach the addition of dialogue to your game idea. We talk about using the MDA framework to find your game's main aesthetics, its core experiences, and find ways to make your dialogue advance them.

[This post first appeared on our blog at Tea-Powered Games]

At Tea-Powered Games we talk about dialogue quite often, but what is it that good dialogue could add to your game?

In the case where you use dialogue to add new kinds of play to your game, it gives players a change of pace, a new mechanic to play with, or different kinds of goals. If you tie dialogue to your game’s current mechanics, fans of those mechanics will get to interact with them more, and experience more interesting variations. More importantly, entirely new stories and games become possible when you start thinking about conversation as a part of the game rather than just more words on screen.

It sounds great, doesn’t it? Unfortunately, figuring out what kind of dialogue your game needs is not very straightforward.

Conversation is Complicated

We talk to people all the time, and chances are we talk to them differently depending on who they are, what our relationship to them is, what kind of mood we’re in. There are societal rules and expectations we might try to meet, and different time frames for face-to-face compared to digital communication. And that’s not even touching upon why you’d want to talk to someone. Do you want to get to know them better? Ask them to buy you a coffee? Maybe you just want to pass the time, or you need a bit of human contact to get you through the day. Maybe you’re talking to someone because they’re talking at you and you don’t feel like you have a choice.

What About in Games?

Think about the reasons games give you to talk to someone. Sometimes you have a direct goal, such as purchasing a piece or armor or learning where your ship’s pilot ran off to. But sometimes it’s not about the goal; you’re just helping an NPC or getting to know a party member... right? Maybe. But think about what the sequence of events is. You help this NPC with their rodent problem, and you get nebulous experience points and a small cash reward. You talk to your party member enough, and you’re rewarded with a romantic cutscene. You may have gone in with your own, personal, self-ascribed goal, but the game still rewards you with the only systems it has. And that’s because...

Conversation is Often Separate from Gameplay

You can spend hours running around and shooting things, only to stop in town and select dialogue choices on a completely different interface and time scale. It’s not strictly a bad thing – some games have many systems, and they can’t all work seamlessly together. But at the same time, it feels a bit more jarring when it comes to conversations. Part of it may be that dialogue doesn’t have as much of a pedigree as moving around or fighting in games, so it’s not nearly as sophisticated in its mechanical systems. It’s also not about mirroring or exaggerating a certain physicality – it’s about capturing subtleties.

Of course, some games are playing around in this space. Gone are the days of labelling options as good or evil (for the most part). Now we may get an indication of tone (angry or sad), their effect (someone remembers it, or approves), or something that just happens without markers. These are all steps in different directions, and that’s exactly what we love to see – exploration within this space is how we get better conversations.1

Choosing a Dialogue System Based on Your Game’s Aesthetics

Alright, let’s say you’re thinking of adding some kind of conversation system to your game. Before you make any decisions, let’s plan something that works best for your game. First of all, what’s your game about? Think about your game’s core values and themes so you can find ways to supplement them with the dialogue. As an example, you could use the MDA framework to analyse your game, and find the core aesthetics you want to emphasise. What could your game’s dialogue look like based on your main aesthetics?

If your game emphasizes Discovery, you might highlight a large amount of explorable content, adding meaningful acknowledgements via out-of-the-way corners of conversations (it’s a system you can explore).

If your game centres on Expression and Fantasy, you could give your player lots of options that a person wouldn’t normally have in real conversation (a system to play with).

In a game focused on Challenge, you might require the player to find patterns in conversations and learn how to deploy them effectively to proceed (a system to master).

In a game about Sensation and Submission, you might have a less elaborate setup that’s visually or audibly vibrant, one which allows the player to enjoy the setting without having to make critical decisions (a system to experience).

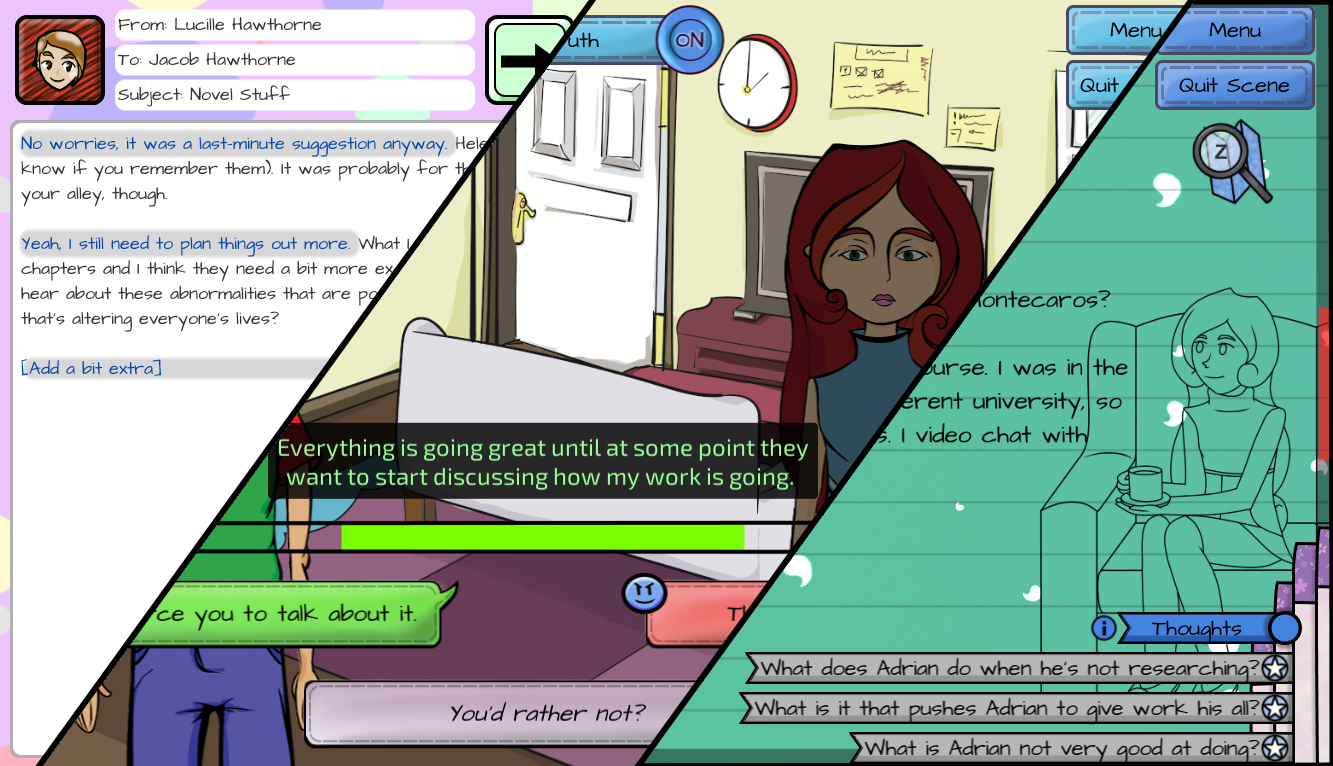

These are just a few, broad examples. You could use different frameworks to classify your game’s goals, based on what you’re familiar with, or just think about the kinds of experiences you want your players to have. Sometimes your aesthetics may not clearly lend themselves to a system, though. In Dialogue, we wanted to capture both Discovery and Challenge. Just as RPGs have dungeon exploration and challenging combat, we created two main types of scenes in our game, ‘Exploratory’ and ‘Active’ scenes. Exploratory scenes were untimed, and focused on opening up new branches of conversation by learning more about the other person and the conversation subject. Active scenes were timed, and players could aim for a ‘high score’ in their preferred approach. We had to make concession for these to co-exist in one game (Explorations are mostly optional, and a lower score on an Active never stops your story progress), but we find that this approach worked for Dialogue.

Inspiration Beyond Conversation

No approach works for every game. When in doubt, draw inspiration from other sources. Was there a conversation you had that really stood out to you, a feeling you want to capture? Maybe you love the witty chats from one of your favourite shows and think that would suit your game. Even in other games, there’s a lot to be learned. Do you want your conversation to feel like an active fight? Your responses might require precise combo input to be pulled off successfully. Does an RTS capture the conversation style you want to have? Then maybe you need to start seeding your discussion points a few turns in advance before you can bring them up directly.

These are some of the methods we use to think about conversation in our games, and we hope they can help you as well. The more we can play with dialogue in games, the more interesting systems we’ll come up with. So think about the role conversations could serve in your game, and how they can best accomplish that!

If you enjoy this take on conversation in games, have a look at our game Dialogue: A Writer's Story on itch.io or Greenlight, or get in touch to find out more about Tea-Powered Games helping you with your game narrative.

1 In contrast with AAA games, plenty of exploration is happening in other circles, such as in interactive fiction. Emily Short’s Galatea and First Draft of the Revolution are great examples, and her website is a good place to find more examples.

Tea-Powered Games is a playful, independent game development company aimed at creating progressive narrative games, and helping other studios improve on their design and narrative as consultants.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like