Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How can we make games that convey important, heartfelt, and meaningful messages to the player through the experience they deliver? In this blog, I describe and explain an approach I've been experimenting with.

Something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately is how to make games that, through the experience they provide, transmit important, heartfelt, and meaningful messages to the player. The conclusion I’ve been reaching is that, if I’m making a videogame, what makes most sense is to transmit the message neither through art nor story, but through what makes games games: mechanics. It’s not a new idea; mindful xp was a collection of prototypes that explored the same concept back in 2013. But it’s an idea I haven’t seen much, and an idea I wanted to try my hand at.

So far, I’ve tested this concept with two games. The first one, Dreams and Reality, was a pretty polished game, but as far as meaningful messages go, it was a really rough and awkward attempt. I decided to focus on experimentation, and started a project called “Us.”, a compilation of weekly mini-games focused on messages about human relations. It kinda failed (I only managed to make 2 and a half of the 4 games I wanted to make), but it was a really useful experience.

These two games are far from enough to say I’m any good at making games that transmit meaningful messages, but I’ve learnt a thing or two on the way, and now may be a good moment to share these thoughts. Before we can get to that though, I have to start by explaining the approach I use to make games with a message, and then show how it works with examples from my games.

Mechanics, Rules and Consequences

To explain the approach I’ve been using, I’ll start by explaining the model I’ve been using to view and design my games lately. It’s basically the model Mark Brown describes in his video on how Jonathan Blow designs puzzles: a game is a system that consists of mechanics which are constrained by rules, and these constraints lead to consequences. For example, in a platformer, jumping would be a mechanic. The typical rule platformers usually follow is “while in the air, the player falls due to gravity”. This combination causes consequences to arise, such as the fact a player can fall into a pit, a player can land on an enemy’s head, etc.

With this model in mind, a designer’s job is to curate the consequences that emerge from a combination of mechanics and rules, deciding which ones should be shown to the player, in what order, and how. For the player, to play a game is the activity of interacting with mechanics and rules to discover consequences. By repeated interactions, the player should eventually be able to reach an understanding of the whole system underlying the game. Through this understanding, the player will be able to face and solve the challenges posed by the designer.

Using this mechanic-rule-consequence model, the approach I’ve currently been experimenting with is to convey messages through consequences. How does this work exactly? As a designer, you’ll begin with a subjective message you want to transmit. There’s a problem though: messages are ideas that can’t be portrayed literally, and thus can’t be put into a game directly. But, through tools like metaphors, you can “abstract” the elements of your message, turning them into something tangible that can be represented in gameplay. Once the elements of your message can be represented by gameplay, you can use them to define consequences that represent your message. With the consequences clear, you must build mechanics and rules that lead to these consequences. I hope some of this made sense, but if it didn’t, I hope the examples later on will help.

How about the player? Since we’re communicating the message through consequences, the player will have to play the game and discover the consequences before he/she can begin to understand the message. And in my opinion, this makes a lot of sense! Just as inferring the themes of a work of art requires analysis, I believe recognizing the message a game is trying to communicate should require the player to interact with the game and comprehend the underlying system. What I find interesting though is that a consequence, due to its nature, is something inherently objective. To see the message then, the player will have to interpret it back into a subjective message.

Nevertheless, this method has an important flaw: it goes against the philosophy behind the mechanic-rule-consequence model. As explained in the video I linked before, the idea is to avoid a top-down imposition of a certain vision, instead designing by defining mechanics/rules and exploring the consequences that arise. My approach is the exact opposite: one begins by imposing a consequence, and works backward to figure out mechanics and rules that lead to this consequence. It’s not ideal, but it’s a natural contradiction. Exploration makes sense when there’s no clear goal, but this approach has one: transmit a message.

Applying These Ideas

My first attempt at making a game with a message was Dreams and Reality, an artsy 2D platformer. The message I wanted to convey was “Dreaming big may be tempting, but if you want your dreams to come true, dream small. Reaching your goals is a series of small and steady steps.” So first things first, I needed to come up with a way to represent “dreams”. I finally decided to go with thought-bubble-like clouds that also serve as platforms. With this metaphor in mind, I needed to design mechanics and rules that led to two consequences: “dreaming big” is tempting but unreliable, and “dreaming small” was less exciting but actually useful.

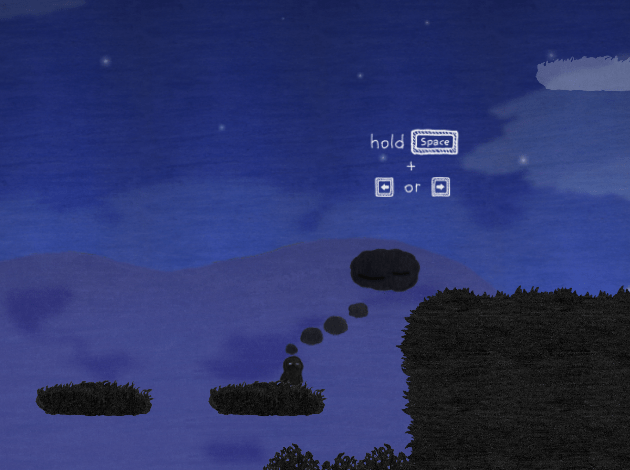

I came up with is a gimmicky mechanic: by holding space you close your eyes and spawn dreams you can jump on to reach higher parts of the level. The longer you hold space, the taller/bigger your dream becomes. To achieve the consequences I mentioned, I enforced two rules: firstly, dreams fade over time and eventually disappear; secondly, bigger, taller dreams fade faster than smaller ones. Thus, if the player dreams too big, the dream fades too quickly for the player to actually climb it. This makes small dreams the only viable way to advance in the level. Finally, I designed the level in a way that tempts the player to dream big by placing goals in high yet visible places.

I think I did a better job with closeness, one of the mini-games from “Us.” In this case, the message I wanted to transmit was that “Being close to someone means you might be opening yourself up to pain you wouldn’t feel otherwise, but it also gives you the chance to feel happiness you couldn’t feel in any other way”. To represent the idea of “being close”, I used the simplest metaphor possible: the message talks about emotional intimacy, but “being close” can also refer to physical proximity, and space is a much more tangible game mechanic. As for the consequences, I needed to aim for a risk-reward kind of system where physical proximity was a risky and thus possibly negative move, but at the same time, had much greater rewards than the ones for staying far away.

The game’s main mechanic is quite simple: you play as the avatar orbiting the person in the center, moving between the inner and outer orbits. The goal is to fill the bar at the top and “unlock” additional orbits by gathering blue stars and avoiding red stars, both of which have a bigger/smaller effect on the bar depending on their size. The most important rule here is that stars decrease in size as they fly away from the center. What’s the consequence? Being in inner orbit makes it possible to get hit by a red star, but at the same time, being close is the only way to get big and useful blue stars.

Lessons Learnt

As much as the goal may be to transmit a message, it’s useful to remember that people usually play games for one reason: entertainment. If they aren’t having fun or enjoying your game, they will simply stop playing. If they enjoy it mildly, they’ll play it once and then forget about it. Only when they truly enjoy your game will they look past the superficial aspects and start to care about interpreting it. Just be careful not to go to the other extreme: focusing so much on making the game fun that you forget the message. It happened to me with a mini-game from “Us.” and while yes, the final result was fun-ish, I ultimately made a game that was bloated with mechanics, rules and consequences that diluted the main consequences and messages I wanted to transmit.

While this article is about transmitting a message through mechanics, it’s important to remember that the rest of the game’s components such as art, audio, and narrative can (and should) be used to reinforce the message. This is important because ultimately, due to their metaphorical nature, it can be difficult to even notice a message exists. If the goal is to convey a message, the game must do all it can to encourage the player to analyze and interpret it. In Dreams and Reality, the game begins with an “artsy/philosophical” narration which sets the player in the mood to find meaning in how the game is designed. Here’s a let’s play that shows this very nicely. In closeness, an important visual detail is that the avatars are human shaped. So that the consequences may be interpreted in the context of human relations, I added an element that explicitly relates the game to people.

A probably obvious piece of advice I completely ignored in Dreams and Reality is to avoid explicitly telling the player the message you’re trying to communicate. The game ends with a narration, just like how it began, but this time it just goes and says the message. And the worst part is that I added this out of fear; I thought that maybe the players wouldn’t get it. But many players resented me for it, saying it cheapened the message or lessened the game’s charm. In the end, it’s quite similar to why people hate when games have hand-holding pop-ups and companions: satisfaction arises from solving the game on your own. If we want to make games with messages that feel truly meaningful, we have to let the player find them on their own.

Closing Thoughts

I’ve only just began to experiment with this approach, but I hope to keep on doing so. There are still a lot of things I’d like to test out, like learning how to use narrative better, representing complex messages through interconnected systems, introducing messages through the introduction of mechanics, etc. While these experiments are just small, bite-sized web games, I hope to develop a structure that’s flexible enough to be used in a full sized commercial game. Will it work out? No idea, but at least it sounds like fun!

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like