Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"In any other game, this would just be bad UI/UX. But here, it is essential. The machines' limitations and clunkiness become an antagonist of sorts. Each device is method acting, permanently in character."

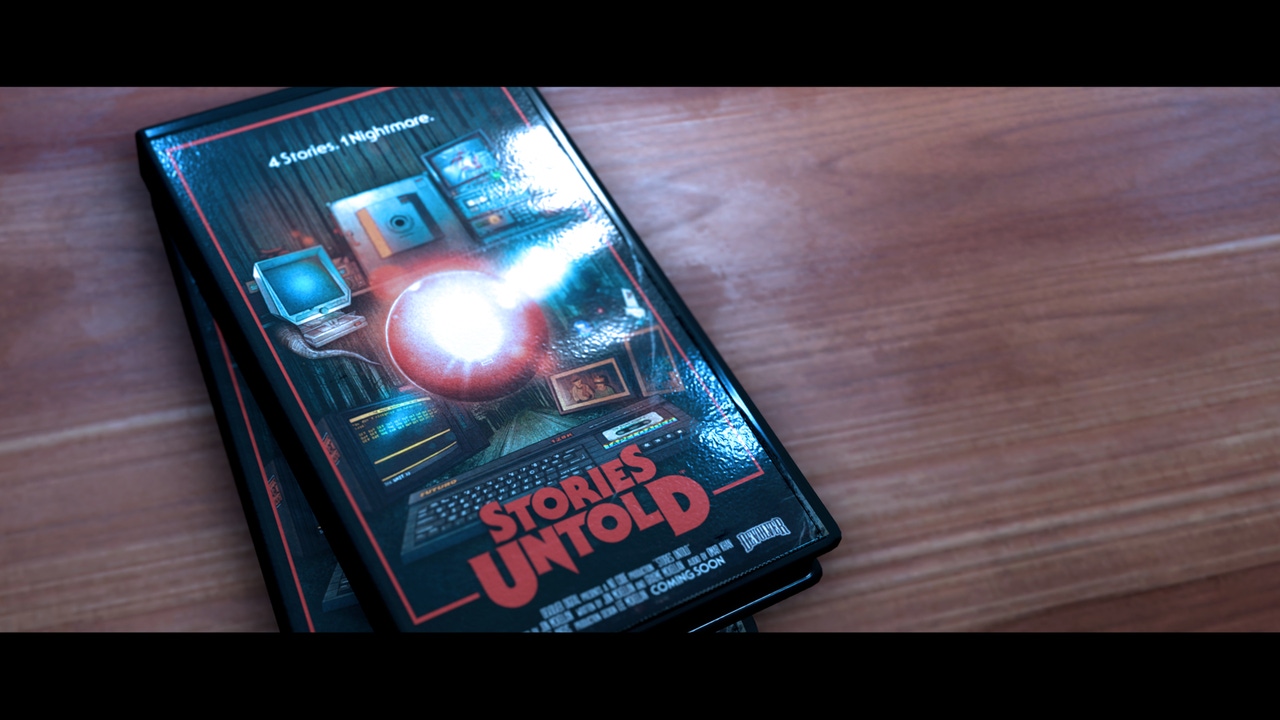

Stories Untold is a game about stripping away the pleasant sheen that nostalgia places on the past and seeing it for what it is. It does so by presenting players with facsimiles of old technology, and forcing them to wade through clunky UIs.

The game is difficult to describe without spoiling its many surprises. Suffice it to say that it's episodic, and it presents players with several different workstations festooned with various pieces cutting edge technology--well, it was cutting edge technology in the Reagan era.

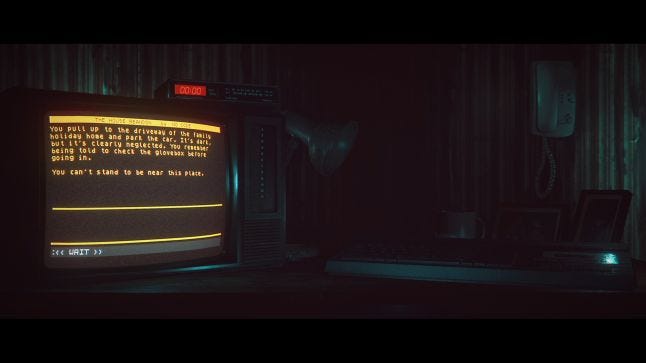

In Stories Untold, players interact with vintage machinery, vintage computer hardware, and vintage software, including an old school text adventure. There is often a sense of joy to be found in re-experiencing these things in our minds. However, the reality of playing with these things often doesn't live up to our memories.

This is the arc Jon McKellan, one of the developers of Stories Untold at the studio No Code, wanted players to go through. "A lot of the game is about discovery and subverting expectations," he says. "The initial reaction from people who remember these machines is a smile and a sense of rediscovery, excitedly saying 'I had one of those!!'. For younger players, it's a comical 'Oh my god, these things were so bad!'."

"We always let give players a moment to enjoy the initial interactions," he adds. " As they get used to it, the realization kicks in that these things were never actually fun or easy to use."

By framing the game with machines that many have pleasant memories with, and then tearing the nostalgia away by making the player face an ugly reality, No Code's difficult UI's force the player to go through those emotions along with the in-game character.

"By the time you are in the thick of it, the machines' limitations and clunkiness become an antagonist of sorts. In any other game, this would just be bad UI/UX, but here, it is essential. Each device in the game is method-acting. They are all permanently in character." says McKellan.

The 80's motif was an important starting point for this game about exploring memories, and not just because the tech from that era offers that requisite clunkiness that the developers sought. "It's a way of luring the player into a false of security, to be honest," says McKellan. "Nostalgia has this amazing ability of making us forget the bad things in the past, and only focus on the good. People get warm and fuzzy when they see toys or computers from their past, and want to recapture the original feelings."

It helps bring the player into the game's world and narrative. If the player has pleasant memories of this old tech, they approach the game's tech like the characters in the game might. They approach it with reverence, awe, or laughter. It feels like something silly or pleasant, exactly like looking back on old memories. These unwieldy old machines are so silly! I remember seeing stuff like this!

At the same time, these machines are challenging to use. Playing around with them carries that natural sense of fun that comes from clicking buttons and playing with knobs (something that can be seen in many of the ALT.CTRL.GDC games).

"What we do is lure you in with that nostalgia, then make those machines uncomfortable, mundane even, to use." says McKellan. "Strip away that warm feeling, view it with a more honest lens, then have you use them to do things you don't want to do. Each episode has you being pushed and coaxed into going further than you are comfortable with, and that contrasts well with the nostalgia."

He says that this ties directly into the recurring theme throughout the game of returning to past memories; being forced to relive events you might not be comfortable with. "The 80s motif helps manifest that idea outside of the direct narrative. It's just the nature of rose-tinted-glasses. Nostalgia creates a safe, warm place to play, and to play out horror there makes it that bit more effective." says McKellan.

The fun of playing around with these machines will soon wear thin with most players. "The annoying part of repetitive use is just a thing that happens on the journey to the narrative truth, ramping things up for the end." says McKellan. "The link between the stripping of nostalgia and deliberately obfuscated bad memories is something the player feels directly, and the character is experiencing too. So that middle stage of bringing reality to the nostalgia is essential to get the player into the right mind set for the story that unfolds. It's the closest we can get to have you feeling similar things to the protagonist."

"Each machine is a character in the game, and it was important for them to be authentic to get the point across," says McKellan. "That battle between nostalgia and reality. Some of the machines are clunky the point of being straight up difficult to use, and that was a choice we had to wrestle with a lot. It can turn people off."

"However, what we had to remember was that these machines have relatively simple functions, and to streamline or strip back the clunkiness would pretty much result in 'Press X to X-Ray,' and then the game is dead. The intricacy to the operation processes is a big part of the gameplay, so it to be 'real'."

The complexity of how these machines worked created that necessary second step to bringing the player into the game's world. But No Code envisioned a three step process.Nostalgia would draw the player into a place of pleasant memories, the clunky nature of the UI was key to bringing the player to the middle step - when things started to lose their sheen.

And then, out of nowhere, everything goes wrong.

What was, only moments before, a source of irritation, becomes the player's only anchor in a world that is falling apart. In the final act of each of Stories Untold's episodes, things begin to grow more horrifying and surreal every moment, and all the player can do in these situations is fall back on what they know of the game's UI to get them through.

"Without spoiling too much, we want players to gradually discover the interface and workings of each system, so that when we flip the switch, we get to focus on the moment and not mess up the flow by re-teaching you gameplay at a crucial point in the story. There's a lot of deliberate repetition at play, so that when the time comes, you know roughly what to do already." says McKellan.

"By the fourth episode, they are the only things that behave as you would expect, even though the meanings have changed, and are the only anchors you really have," says McKellan. "I thought that idea was fascinating as we flip things on their heads for the player, that we keep the interactions grounded so that in all the confusion of what the hell is happening, you don't need to learn anything, you already know it well enough."

This could have been a real tripping point had the team at No Code not put in those moments of repetition. The complicated, unwieldy UI, having lost its charm, could just be making the player angry at this point in the game, which would break immersion. By taking the time to bother the player with the forced repetition earlier, it mirrored the character's emotions while also training them to make these controls, however odd, second nature by the final act. In doing so, it ensures the players would know these strange systems that they could just experience the horrific turn and what it entailed.

"A large part of the game is about pushing the player to do things they might not feel comfortable with. Whether that is going against your gut instincts or literally doing bad things, the player had to feel guilt in some way."

This is the entire point of Stories Untold - that exploration of things and memories and places and events that players may not want to. It's about moving beyond that sheen of nostalgia to the darker memories underneath - about moving from a place of false joy into a more upsetting tale beneath. It forces the player through the false happy times into the dark things that lay beneath.

"As a kid, these machines, computers, whatever; they are all magic. They do stuff we can't understand, so I think that comes back to players," says McKellan. "We know the reality now as older people, but we remember being so wowed and amazed. The thing is though; the machines throughout the story are always exactly as they are. They don't change in what they do. "

He says that when players reach the climax of the game, they will realize that each machine was a way to get closer and closer to the truth. "The theme was more that these inanimate objects can all hold a story of their own, or rather contribute to telling a bigger story," he says. "Something as seemingly innocent as a frequency generator can take on a whole new meaning."

Read more about:

Horror GamesYou May Also Like