Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this nuanced look at game storytelling Die Gute Fabrik's Hannah Nicklin walks you through how she joined up with the Mutazione crew to flesh out and build the narratives of this mutant soap opera.

The Gamasutra Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including building an adaptive tech tree in Dawn of Man, creating comfortable UI for VR strategy game Skyworld, and creating the intricate level design of Dishonored 2's Clockwork Mansion.

Hi, I’m Hannah Nicklin from Die Gute Fabrik. I am the narrative designer and writer for Mutazione – a mutant soap opera where small-town gossip meets the supernatural –which was released in September 2019 on Apple Arcade, PS4 and PC. I’m now CEO and studio lead of Die Gute Fabrik.

Before transitioning to video games as a main practice, I also worked as a playwright and theater-maker, and I have a PhD in the spaces between games and theater, and their uses as anti-capitalist practice.

My training is in theater-writing, and I correlate the role of narrative design very strongly to that of ‘dramaturg’ in theater. A dramaturg’s job is to look at the structure of the storytelling, and storytelling through the structure; it’s a systemic look at narrative which I find doubly satisfying as a practice in games, where player choice becomes a new factor, and narrative design tools a new limitation.

My early career practice as a theater-maker very much revolved around form-led design – finding the story you wanted to tell and then finding the best medium to tell it in, and also working tightly to brief. My theater-writing training focused on complex characterization, elegant exposition, and knowing when to break the rules usefully. This all equips me well for writing in games, as I can enter a project halfway through (as writers often have to) and be tools-focused: what are the affordances of existing tools in telling a story? What additional tool or feature would shape this storytelling most usefully? Alongside dramaturgical instincts about time, structure, and giving themes room to emerge naturally.

Parenthetically, I strongly recommend game designers seek out non-traditional theater and performance events near them as part of the work in other media that influences them, I think the perspective is really valuable for people working in games.

Vocabulary

I think specialist vocabulary around writing is sometimes thrown around a little interchangeably, so from my own perspective and learning, this is what I mean by these specific words (some of it is Aristotle by way of E. M. Forster, some of it is my own):

Story: the total thing you will communicate (you might call it the lived experience of the characters).

Story-world: relevant when the game is set somewhere other than our world/reality.

Plot: the events that you choose to show in their specific time-linear order.

Narrative: The entire design of the telling of the story – for example, a narrative can contain several intertwining plots (in TV you might have an A plot, a B plot, and a season-long Ur plot – a narrative might also tell plot elements out of sequence.)

Narrative design: The specific discipline in game-writing which encompasses the design choices around: player interaction, choice and consequence, space, embodiment, game feel, mechanics and time in order to tell the story.

As a working example: in an episode of Star Trek DS9, the story-world is that of the Star Trek universe. The story is one of a group of Starfleet employees attempting to mediate in a border-town space station between a community recently freed from occupation, and their occupiers. The plots may be ‘the barman has a comedy scheme’, ‘the previous insurgent has to tackle some of the moral grey areas of her previous activism’ and ‘the Captain has to keep the fragile peace whilst also being a good father to his son’. The narrative is the order of scenes, what they depict, who is in them, and how they interact throughout an episode.

When I came to Mutazione (pronounced as it is in Italian [muh-taht-zee-own-ay] /mutatˈʦjoËne/) the game had been in development for around 6 years (though not all full time). As part of my brief I was presented with a fully formed story-world and set of characters, and a plot for the overall game. There was a system for writing dialogue which wasn’t yet connected to the game, and a majority of the animations were already made -- meaning I had a limited palette of emotional expression.

I was initially brought on to triage the writing. It quickly became clear, however, that there wasn’t yet a plan for the structure of the storytelling, how time worked, nor any clear logic systems for progression. This kind of systemic thinking suits me and as I began to collaborate (with permission) beyond my initial brief I was soon offered the lead on shaping the means and the telling of the story at the heart of this story-driven game.

At that point the brief became to implement Nils Deneken’s artistic vision to produce a game which was:

Driven by an ensemble cast of characters.

A soap opera.

Centered around a theme of looking at a community aligned differently with nature.

Built on a clearly defined and pre-existing story-world and plot.

It’s important to admit, I think, that as many decisions are made in game development by process as by intent. Some processes you design, some you do not. My position on the team wasn’t one where I had full license to redesign the structure of the narrative and elements of the plot until the final year of development.

My involvement with the narrative design grew as:

The Creative Lead built confidence in my abilities to tell his story and change them positively without his oversight (it is a lot to hand over your story to someone else!)

I built my knowledge of the tools and systems in place to tell the story with, and was able to ask for refinements.

I was able to put in place systems for overview (many spreadsheets and filter functions).

We made some cuts. I love cuts. A single cut can allow you to see all of the lines of intent connected to it, and understand if it all needs to come apart, to serve the story best.

This is a quality of joining a project mid-way through and is at the base of many decisions and choices present in the game, which are still effectively first draft. My writing pals in other forms would be appalled at how much first-draft makes it into the ‘finished’ game.

One of the things that was presented to me early on was that this was a soap opera. As a form-led practitioner I made careful note of the genre I was being asked to write within, and aimed to therefore make design decisions to serve this.

A few reactions to the game have focused on the ‘soap opera’ label as ‘wrong’ because they think it’s a ‘good’ game (um, thanks, though!) Genre is fairly neutral to me, on the whole, but I can understand that to non-writers, it is not. Nor is that reaction unique to games. In books, film and TV, ‘literature’ and ‘drama’ are often seen as the only place for quality. The masterful romantic comedy Pride & Prejudice is often placed in the ‘literature’ category, rather than in the reams of pink-covered rom-coms (give me a historical romcom section! File A Midsummer Night’s Dream there!) Rom-coms and soap operas share that they are typically seen as ‘feminine’ forms of storytelling (they often center female characters/experience), and therefore somehow ‘lower quality’. I would wager there are as many bad action movies as there are rom-coms, but while we might expect an action film to be trashy, far fewer people sneer.

So I’d like to stake ownership of the soap opera form – soap operas are not ‘low quality television’ they are (to my mind) defined by being long-running, character-driven, ensemble-cast, slices of life. They share a lot of their qualities with situational comedies, except they tend to be drama- rather than gag-driven. And to my mind a soap opera is an excellent form to work with in video game storytelling.

I feel strongly that the hero’s tale is a format best suited to a play or film-length story. Perhaps 5-6 hours max. After that point you will find yourself generating false jeopardy for the central character, and those around them who enable their journey will begin to feel thin. (Of course, there are examples that are successful, all good writers can work against the grain of a form as well as with it – but the key is to do so consciously).

A soap opera on the other hand – in games, and in a game with exploration rather than linear ‘corridor’ gameplay such as Mutazione – the ensemble cast allows you to fill a world, to help it feel like it exists beyond the tip of the iceberg you encounter through your gameplay. It can offer A, B and C plots; intrigue, comedy and drama; through different characters, no longer demanding one character hold it all.

The genre ‘soap opera’, and the form of the gameplay (exploration plus conversation) made me convinced that I would need to make narrative design decisions that built a world that felt like it was full, that it existed before you arrived, and would continue to exist after you left.

When I started on the project there was no system for managing time. There was a clear idea that there were different days in the story, but it was just imagined that time would slowly move forward, and the conversations you had would unlock ‘later’ ones in the plotline.

For the purposes of the brief, however, I felt this needed to change.

Creating routines among the characters by using specific times of day would enable a sense of a world which could be independent of the player’s journey. It would also allow us to impose pacing – to develop character journeys as well as plot lines. Time is a vital part of any story, because it affords us the ability to show change. A key principle for me in writing an ensemble-cast narrative was to have all of the characters in some way changed by the events of the story.

I worked with the excellent narrative system design team (Christoffer Holmgård and Morten Mygind) and Nils, along with some incredibly valuable work from our intern Sarah Josefsen, to create a more formal system for time in the game.

This is how the story is told in place and time:

There are 8 ‘days’ in the game (which we also call ‘chapters’), every day is made up of 7 times of day; dawn, morning, lunch, afternoon, evening, night, and late night.

For each of these times of day there is a ‘town schedule’ a huge list of every scene in the game. Into which I place ‘activities’ which are a unit made up of 1-X characters, placed in a particular place in a scene, with a default set of animations.

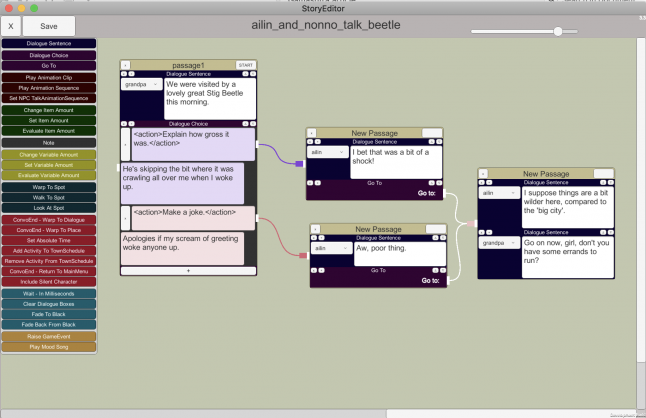

I draft conversations in a Story Editor tool – this is the series of choices and dialogue that you have when you engage with a character or group of characters (including exchange of items, etc.). It knows who is in an encounter, and what they say.

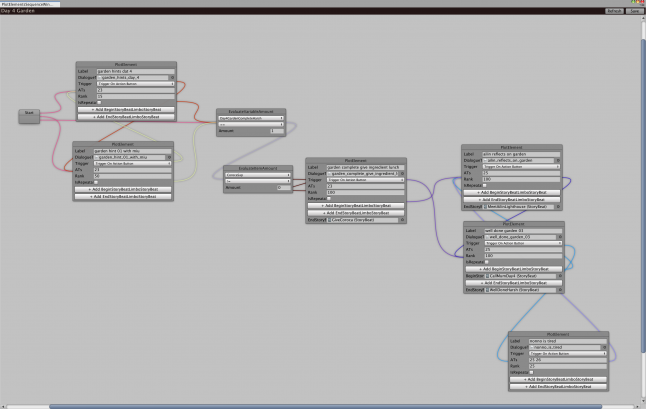

I place conversations in a plotline – which can gate access to a conversation based on previous conversations, inventory items, the state of a garden, or variables I have set up in several conversations. (It looks like a logic tree)

Every plot element in a plotline has one or more times of day value it is available at – we call them ‘absolute time’ or AT, i.e. an AT from day 3 might be ‘15’.

This ‘final’ narrative design for time was probably only settled about 1.5 years before launch. When loading a scene, the game will therefore check the town schedule for activities due in that place and time and position the 1-X character(s) accordingly. The game will then check if a plot element has assigned a conversation to those characters in that time, and (if the flow of logic in the plotline makes it available) there will be a ‘conversation’ icon above the character(s’) heads. Finally, plot elements can also be assigned a priority in case two conversations from two different plotlines are possible, and you wish to say which is the more important.

All of this means that during any one time of day any one of the characters can only be in one place. They can be moved with a warp – but this is rare. This means they can develop habits, and their presence in the world feels like it doesn’t just serve the player. Mori spends her lunches serving food in the Stir Fry, or Spike and Claire always hang out by the harbor in the morning…

Plotlines originally spanned much longer periods of time – conversations were available across multiple times of day, or even multiple days. But as we refined the systems, I felt like this worked against the feeling that you were dipping into an already running stream. I decided to make it so you could miss earlier conversations in any plot that wasn’t a vital part of the A plot. It also made it much easier to make sure that you were having a well-paced narrative experience, as I only had to imagine the multiple orders in which you could experience each time of day – which could sometimes be around 20-30 conversations on a busy afternoon (there are around 750 conversations total in the game).

It also meant I could gate progress. To combine freedom of exploration, a well-developed world and fairly complex series of plots, and a strong linear understanding for the player, it was important to be able to pace through gating progress.

After disposing of the idea of free-running time, we worked with the concept of ‘story beats’ and ‘story ticks’ to gate it. ‘Beats’ were mandatory conversations you would need to have to move on to the next time of day, and ‘ticks’ were allocated to a conversation on the basis of how substantial it was (2 ticks for a B plot, 1 for a C plot, 0 for an incidental) – the idea was that ‘ticks’ would make sure you’d got enough ‘meat’ before you moved on. During a busy time of day (lunch time day 3, for example) you may need 2 beats (2 specific convos) and at least 8 ticks to progress (points amassed from any other convo bearing ticks).

However, through discussion with the team (this time adding in Doug Wilson, audio engineer and an incredible gameplay designer/thinker), we began to feel like it was important to be as clear as possible to the player about how time worked. And that the ‘ticks’ were too complicated to communicate in a way that wouldn’t break the flow of the narrative: if you began to collect ‘points’ conversations would begin to instrumentalize rather than humanize the characters.

So we decided to cut the ‘ticks’ and instead work on making the beats visible to the player in a way that was both diegetic (of the story-world) and in the layer of UI (much of which was designed by GUI whiz Óscar Losada with Nils’ input).

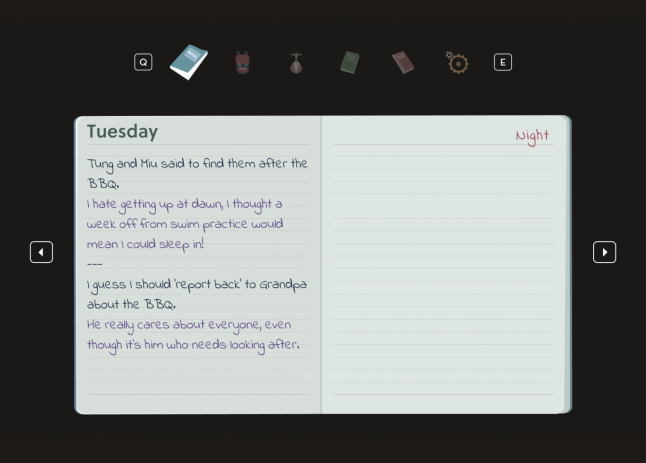

This led to the idea of the ‘journal’. In the journal we would list the ‘beats’ – the conversations or tasks which (when completed) would move time forwards. We emphasized this with a change in the UI symbol for the ‘last’ beat conversation in a time of day – when a conversation will move time forwards it will show a ‘timer’ symbol.

The UI layer in a game is – to people literate in computers, at least – rarely seen to be a part of the story world, and instead part of the means of navigating it. Too much UI can interrupt rather than enable navigation, but when made well, UI decisions are like marking symbols on a map – they telegraph certainty and intentionality. The intention of the timer symbol is to tell the player we want to give them the tools to know when their actions will move time forward. After 2-3 times of day, the number of conversations available that aren’t listed in the journal should make it clear that if they wish to explore all the possibility space of one time of day, they should leave timer conversations to last.

The final thing was to find a ‘voice’ for the journal. We looked at a lot of examples, including Life is Strange, Night in the Woods, and the to do list from the (at that time still in progress) Untitled Goose Game – should it be closer to the neutral ‘voice’ of the UI? (i.e. this is us, the game designers, helping you navigate), or should it be a place for characterization, and marking where you’ve been?

In the end we leant towards the latter. The journal now shows the mandatory ‘beats’ for each AT in the form of notes taken by Kai about tasks which Kai has been given by herself or others. “I wonder how Miu’s feeling today” or “I promised Grandpa I’d go get something from Yoké in the Archive”.

They are not 100% transparent: the former, for example, means you need to remember that Miu lives in the hut by the Rooftop Garden. We also try and show Kai beginning to understand principles as hints to the player in case they haven’t made those connections yet. We do this primarily in the follow-ups – giving the player a diegetic as well as instrumental reason to return to the journal – to see what Kai thinks about what’s happening. The follow-ups fill out when you complete a beat - they are sometimes for realisations (still instrumental) but always partly or purely characterization. E.g. Kai writing in all-caps “SADFACE” after witnessing a breakup.

One of the first things you’re often asked about interactive narrative is ‘how important are the choices’, ‘do they matter?’. I’d like to think all the choices characters make in a game ‘matter’, but the amount of control you have over them, and what they in turn affect, is often seen as the sum of how complex or accomplished a piece of narrative design is. Indeed, a lot of games discourse tends towards judging the accomplishment of games on how close they get to the ‘real’ world of choice and consequence (what is that even under capitalism anyway? lol).

When asked this question with regards to Mutazione, I like to talk about the game having ‘multiple middles’ rather than ‘multiple endings’. In conversations I very much use the Kentucky Route Zero model of choice – coloring how the character plays the situation, but not letting you choose who the character is. Are you attempt-to-be-articulate Kai? Or are you diffuse-the-situation-with-a-joke Kai? Either way, you’re still Kai. The conversations branch; you might access different reactions, memories and stories; but they come to the same place at the end.

Instead there is a great deal of choice in terms of which B and C plots you dig deeper down into, who you make deeper connections with, and how much of the complex and thoroughly plotted history you uncover. Multiple middles.

To re-cap on the brief that I started with, that Mutazione is:

Driven by an ensemble cast of characters.

A soap opera.

Centred around a theme of looking at a community which was aligned differently with nature.

Built on a clearly defined and pre-existing story-world and plot.

The tools and decisions I just discussed were all tools and decisions aligned with these goals; giving characters habits and routines, constructing plots which progressed whether or not you had found the first or second conversation gave a sense of a pre-existing and alive story-world in which you weren’t the only protagonist.

The soap opera form was served by therefore being able to interweave many plotlines, and to allow the player to discover histories and participate in different dramas past and present.

The multiple middles also allowed me to build characterization which was rich and complex, meaning that the full ensemble cast felt real and a part of the texture of the place. I worked carefully in the dialogue to imbue each character with a distinct voice – from cadence, idioms, style and manner of speech – and gave each character an arc defined by time, which allowed all of them to develop and change (and as some people do, stay stubbornly the same).

And finally, in being transparent about time, and combining this with the freedom to explore Nils’ wonderful wilderness and environments the narrative design was able to reflect the theme of a closeness to nature, and the main piece of mechanical gameplay; the magical musical gardens so beautiful composed (musically and programmatically respectively) by Alessandro Coronas and Doug Wilson. I made narrative design decisions that focussed on the characters as complex, rich, and a little different for the smallness of their community. I wanted getting to know them to feel like coming across a number of new plants you’d never seen before, watching them grow, tending to them where possible, and allowing them to surprise you.

I set out to build narrative design that would allow the player to choose their own pace: to push at the central plot, or to meander, wander, and grow at their story at their own pace. The themes of the story are tough – among the everyday it deals in trauma, colonialism, infidelity, ageing and illness – but the game is often characterized as ‘gentle’, I think, because of the ‘multiple middles’ opportunity to pace your own experience.

Hopefully, as you play Mutazione, none of this narrative design will feel visible; instead it will feel like you are making your own way through a community full of life. A community that has lived long before you, and all being well, will live with you long after you leave.

Thanks for reading this Narrative Design deep dive. If you have any more questions, feel free to check in with me over on Twitter, and please do go and play the game yourself, on Apple Arcade, PS4 and PC.

You May Also Like