Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The narrative process of IGF winner Outer Wilds: How to make a narrative adventure game that takes place inside a astrophysics simulation via paper and digital prototyping.

The following was originally posted on the Outer Wilds blog.

Hey traveler! Alex here, transmitting live from our Story Simulation Center on the moon (the low gravity is great for tossing around weighty narrative concepts). Most of the work we do up here is still under wraps, but today we're going to take a small peek into how we build and test the underlying mysteries of Outer Wilds.

It might have all the trappings of a space game, but I like to think of Outer Wilds as a narrative adventure game that just happens to take place inside a (miniature) astrophysics simulation. As players explore each planet, they discover pieces of embedded narrative that reveal the history of the solar system and the ancient race that used to inhabit it. These pieces also act as clues that point to each other and to special hidden locations, or "Curiosities", where players can find answers to the game's biggest questions (i.e. what's really going on).

Considering the scope and complexity of our narrative structure, it's pretty important that we test whether or not players can understand the clues, find the Curiosities, and piece everything together into a coherent story. Which brings us back to the bit about all of this taking place inside an astrophysics simulation. Testing for narrative comprehension is extraordinarily time-consuming when players can't even access most of your content without (among other things) learning to fly a spaceship. We needed a way for players to test the game's entire narrative structure in a fraction of the time it would take during a normal playthrough.

Our solution was to make a paper prototype that completely abstracted away the space travel and focused on what we wanted to test: the underlying narrative structure.

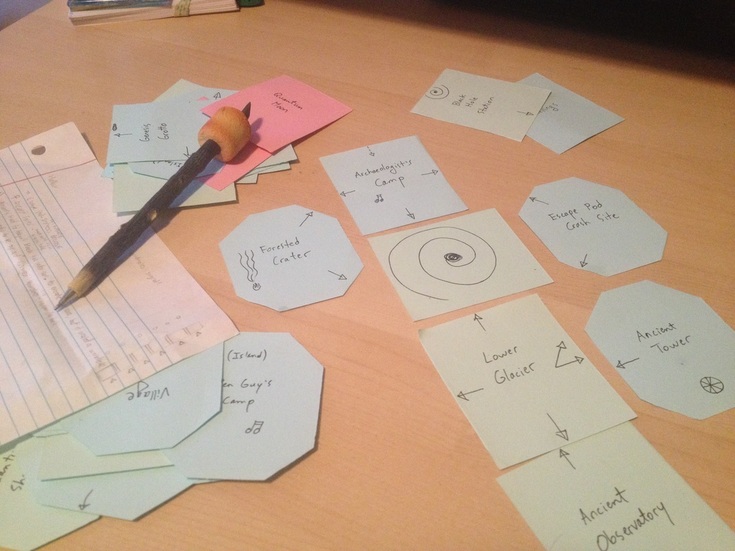

Brittle Hollow as depicted on a bunch of cut-up note cards. I'll admit that is not my best black hole.

Brittle Hollow as depicted on a bunch of cut-up note cards. I'll admit that is not my best black hole.

Major locations on each planet were represented by note cards, and players were given a limited number of turns to move between them each round (if you've played the alpha you can probably guess why). Players could also spend a turn to explore a location, which occasionally meant flipping over the card to reveal hidden information, and more often involved me just describing what they found there.

Overall the prototype worked surprisingly well. It gave us valuable insight into how players were interpreting the clues and understanding the story, and by essentially DMing each session I had a lot of flexibility to adjust content on the fly. We noticed that all of our playtesters quickly resorted to jotting down their discoveries on a notepad, which pretty much confirms that the onboard ship computer should keep track of your discoveries.

The next step, which was both totally unnecessary and absolutely worth it, was to recreate the paper prototype in an open source Java library called Processing.

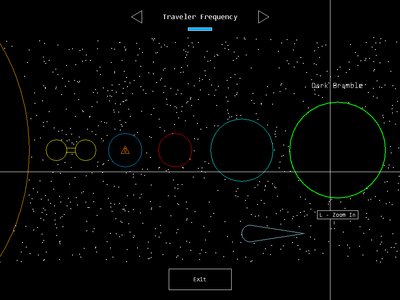

This is now a thing that exists.

This is now a thing that exists.

In addition to the basic structure of the paper prototype, the digital version added simple probe, telescope, and ship computer mechanics, essentially making it a feature-complete demake of Outer Wilds.

One of the most surprising results was that the telescope mechanic worked better here than it does in the actual game. Whereas players tend to forget the telescope exists in the real game, players used it quite often to hunt down signals in the text adventure. As a result, we're actually going to modify the telescope in the real game based on the design of the text adventure!

The solar system in glorious 2D vector graphics!

The solar system in glorious 2D vector graphics!

Somewhat ironically, the biggest problem with both prototypes is that they were too effective at concentrating the game's narrative content. The story in Outer Wilds is designed to be experienced piecemeal over a long period of time, not devoured in one sitting. Several players were overwhelmed by the barrage of information learned at each new location. Of course these same locations are far more spaced out in the real game by, you know, space. Still, it's good to know that a bit of downtime is actually necessary to give players a chance to digest new information.

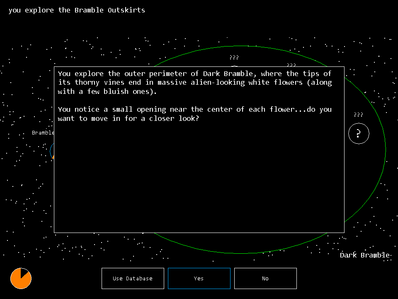

A hint of things to come...

A hint of things to come...

Between these two narrative prototypes we now have a much better idea of what the game feels like when all of the pieces are put together. Our next big challenge is to translate the descriptions from the text adventure into fully realized 3D spaces. We've got a lot of content to make, but it's nice to know that all of it is probably going to make sense.

Onwards!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like