Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

We speak with Dene Carter, formerly creative director on the Fable series, about his latest indie game The Horns-- a cosmic horror game about choice and survival.

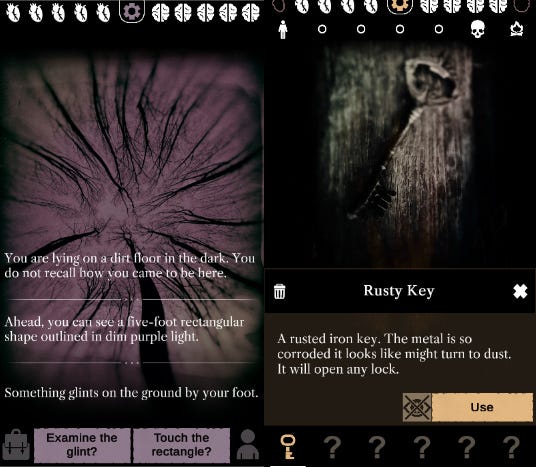

The Horns is a tremendously evocative text horror game for iOS, PC, and Mac that puts the player in a world overcome by monsters, forcing adventurers to make difficult choices in order to survive. We spoke with the game's developer Dene Carter via email to ask about designing his world of cosmic horror.

I’m Dene Carter, and I was the creative director for the Fable series on Xbox, and one of the original Dungeon Keeper core team. After realizing that working in AAA didn’t allow me to do the things I love (making music, art and coding), I started Fluttermind. I released Flaboo!

In 2010 while I was creating my game-dev tools, and then Incoboto in 2012. Incoboto did really well, and was nominated for a BAFTA. Since then I’ve been working on a weird game about magic called Bemuse/Wardenclyffe, and released a little retro shooter called Spellrazor with 27 different fire buttons for PC and Mac.

The game started off as a marriage of a brutally difficult and dark tabletop game called Kingdom Death: Monster and a little PC game space survival game called Capsule.

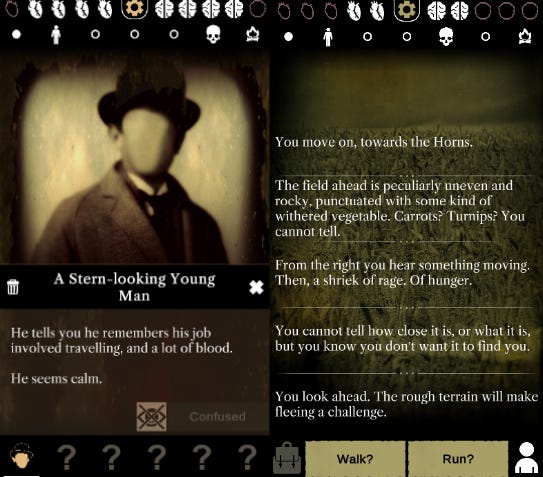

Originally, you were physically traveling up a long winding road on the screen toward some weird far-off goal. You’d come across little dots off the path and have to decide if you were going to detour or not in order to gather water, food and weapons. As I developed the game and tested it out on friends, I found that all of the ‘physical’ stuff became less and less interesting to both me and the players, and so I decided to focus on finding a way to generate a non-linear narrative instead, making the game more mobile-friendly in the process.

[...T]he game is structurally closer to something like Reigns. There’s a lot of code in the background that crafts the story for you based on what you’re doing, what you’re carrying and who is traveling with you. Since there’s a lot of programmatic complexity under the hood, and I wanted the game to look good on multiple platforms, I chose Unity. Unlike my engine for Incoboto, it means that I can take it to something like Switch in the future if I decide I want to without rewriting the whole thing from the ground up.

The actual story of the game was based on a Call of Cthulhu game I ran for some friends a few years ago, but also takes a lot of atmospheric cues from the writer Thomas Ligotti.

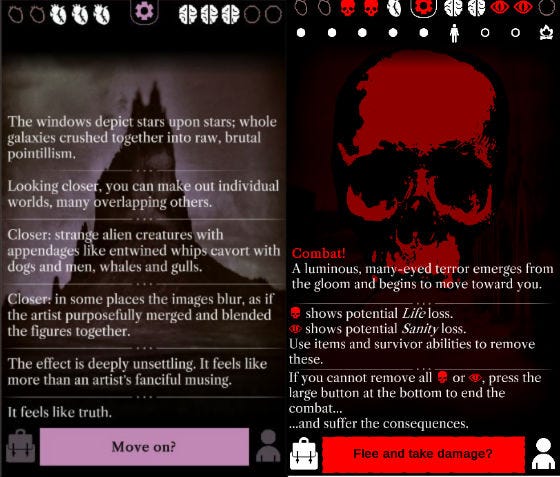

In terms of actual content, the game isn’t that Lovecraftian. It’s not about investigation, it’s about survival. The world isn’t about to be filled with monsters; the monsters are here already, and have utterly overwhelmed the planet! Most Cthulhu games are about trying to save the world. In The Horns, it’s already far too late to stop the bad thing from happening. The world is already lost; but maybe, just maybe, you can find a way to survive... in some manner.

The game is also a personality test to some degree. I’m not really interested in people comparing themselves to each other because that all gets normalized away by social mores. If you tell people their conduct is being broadcast, they act differently. I’m more interested in what people do when they’re not being compared to others and are faced with survival.

As immersive and atmospheric as I wanted all the game's choices to be, they weren't chosen for aesthetic reasons alone. All player decisions in this game came down to one question: "What is the player tempted with and what are the costs of them giving in to that temptation?"

If a player decides they don't want to explore at all, they can actually circumvent 90 percent of all 'deep' choices in the game. However, if they do this, they'll almost certainly die when they next encounter a monster. If you've nothing in your pack, and nobody left alive to help you, you're going to die!

As such, the choices are all disguised variants of 'Will you risk X to get Y'? The process of making this into a whole game consisted of looking at the distribution of trade types in each chapter and trying to find ways these could be made into interesting pieces of narrative.

For example: Survivor Loss for Unknown Item became "Risk the life of one of your survivors for something in a locked box surrounded by rats?" Sanity Loss for Distance Reduction became "Will you take a shortcut through a passageway filled with strange, alien worms?" Additional Life for Sanity Loss became "Will you eat a life-giving meal even if you're fairly sure it's made from human flesh?"

For this game, there is rarely a 'correct' answer; circumstances vary too much. The fundamental question is always "What are you willing to do in order to survive?"

I find that in a lot of choice-based games I just take 'the choice that matches my own morality/interests' which often means there's barely a choice at all! Nobody says: "Well, today I'm going to become a cannibal in the game."

As such, I wanted to create a game where the game systems forced people to test their notions of what is acceptable. Because this is always in flux--you might have three companions, for example, and decide that you can afford to risk one--it means that even if players encounter the same story segments they are forced to re-evaluate their decisions with every single new card.

Each chapter's narrative is made from little micro-stories I call 'cards'. The order of these is randomized each time you play. Every single one of the hundreds of cards in the game is also tagged with its 'trade' type in the form of Loss/Gain: Loss=Survivor, Gain=Shortcut, for example.

In the background I'm also keeping track of various statistics like which 'trades' the player has seen and what resources they currently have. These are used to increase and decrease the probabilities of various cards coming up throughout the story.

This reduces the likelihood of your entire party being wiped out due to a 'draw' of cards, and ensures that each decision feels less like the last few you've seen. If I hadn't codified the risks and rewards early on there'd be no way for me to ensure the story's flow was varied and still 'fair.'

Choices are far easier to present in games with action elements, because you can fool yourself that each push of the trigger, or each jump is a 'decision'. Working with pure text, you're forced to be a little more honest about it! Of course, if you want the text to reflect the player's current resources to any degree you end up tagging a ton of text with things like '' or '' so that the story can insert the correct words and make sense regardless of what situation the player finds themselves in.

Sometimes that's just not enough and a scene has to be fundamentally different, which means some scenes need to be written multiple times, with other tags saying "show this text if these conditions are met". Luckily I didn't have to do that too much or the game would have taken considerably longer than it did!

When I was working in triple-A my main job was ensuring the game's mood and tone were consistent and correct at all times. This meant keeping that 'tone' in my mind every second of the day, and communicating it with the musicians, animators, artists, designers and writers. So, for me, mood is everything.

Since becoming indie, I've tried to discover the smallest number of things necessary to convey a specific atmosphere. While every part of a game contributes to that atmosphere, the music is probably the most powerful element. Silent Hill would not have been Silent Hill without its trademark music.

The way I usually go about making music is starting off with a blank template in Reaper, then adding an instance of a plugin called 'AugustusLoop' which records a loop of audio. Now, you can record over this loop again and again, but each time you do so it gets a little damaged, and a little quieter. If you do it for long enough the original notes you played disappear entirely. To build up the loops I use a mixture of hardware synthesizers (like my Eurorack Modular and Ciat Lonbarde 'Cocoquantus') and software synthesizers like GForce M-Tron Pro, a recreation of a dusty old tape-based sampler from the 1960s. Sometimes I feed these through ancient tape decks to break the sound a little bit further; these add a lovely warm saturation, warps and burbles, and even dust to the sound.

The more broken the sound the more it matches the game's weird, fractured world. I blend these sounds with a wide variety of other real-world sound sources; everything from things I've recorded myself to weird samples I've found online. There's everything from crows cawing to an old windmill's mechanism winding, and a telephone 'phone unanswered' signal from the 1960s in the soundtrack. I always find something oddly unsettling and lonely about dial tones.

I also enjoy making the audio more than any other part of the project! Making a soundtrack is usually the fastest and most rewarding part of the process. I can't imagine handing it off to anyone else. I've bought way too many synths to justify that now!

The soundtrack for The Horns took me two weeks in total, and I'm really happy with the way it turned out. I've actually released it on Bandcamp for anyone who wants to take a little journey into the world of The Horns without the trouble of deciding if they want to be a cannibal or not...

Read more about:

Horror GamesYou May Also Like