Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Dan Vader, lead writer and designer on the brilliant Grindstone from Capy Games, explains the iterative process that brought about one of the most satisfying puzzle games in recent memory.

A lot of studios have passion projects they work on between contract work and other projects and every once and a while those projects get to see the light of day. That's the case for Capybara Games, the creators of Critter Crunch and Below, who originally started the concept for Grindstone more than a decade ago.

"It didn't change all that much from design to conception, from prototype to what you are playing," said Capy lead writer and designer Dan Vader. "It dates back before Below, before [Super Time Force]. We were sort of in the mode of making puzzle games. We did [Might & Magic: Clash of Heroes], we did Critter Crunch. Our creative director Kris Piotrowski came up with the idea for this blend of color-matching puzzle mechanics with a physical character on the board that moved around the board with the puzzle movement you're creating."

"We always sort of pictured it as a barbarian setting, a brutal setting with a sort of fun cartoonish take on that world," he added. "We prototyped it with just basic animations and static frames on a grid and it pretty much stayed the same throughout the history of its development."

Vader highlighted a few changes that happened throughout the design iteration process as multiple developers at Capy worked on the project off and on between other tasks. The main goal was always to create a satisfying feeling whenever the player could pull off a large combo.

Grindstone shares a lot of DNA with other puzzles games. There are still different colored pieces you need to clear, items you can use to make that easier, and enemies that will attack you if you make a mistake. But Capy wanted something slightly less casual. They wanted Grindstone to be challenging but in a meaningful and satisfying way.

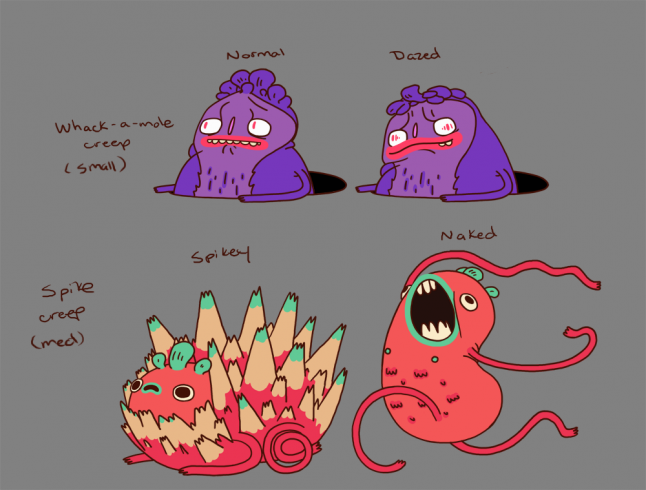

Originally the creeps -- the little monsters you attack on the board -- would be able to deal damage in every direction around them once they went aggro. In the final version, only special enemies would be able to deal damage this way, and the more common creeps could only attack in four directions -- up, down, left, and right.

That small change was a bit of a breakthrough for the game's design. "There was something about it, we kept thinking about why we were so frustrated when we were playing this game," he said. "It was just so difficult so we took out the diagonal angles, those were so dangerous, and that just freed things up and made the board so much more maneuverable."

Grindstone is unique compared to other puzzle games in that the player is limited to making moves from their position on the board. It was important for the player to have a number of options to keep the action going and limiting enemy attack patterns helped prevent the player from dying constantly.

Grindstones, the gems that pop out whenever you get a combo greater than nine creeps long, are at the core of making the game work as intended. They help connect combos of two different colors, which is key to building 30 or 40 creep combos. Grindstones, which were just called gems at the start of the project, were also present as a mechanic from early on in development.

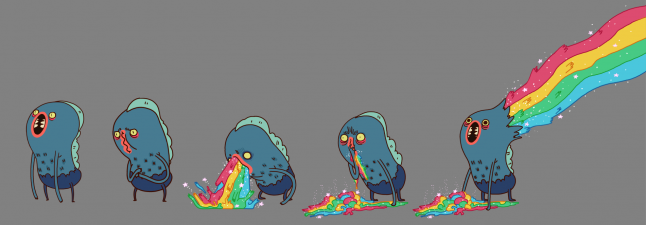

"The design had some parts that were related to more traditional mobile puzzle type things, like every move you made, every kill you made was producing coins," Vader said. "Back then we didn't have blood and there were coins spraying out everywhere. You were sort of collecting coins whether you made a great chain or not."

"So we were sort of frustrated and we would test this with new players and they would spend their time making a five chain, a six chain, a seven chain while we wanted to push them to make these bigger chains," he added. "We realized we were constantly visually rewarding them for anything they did. Anything they made had a reward since we were showering with coins." That led the team to just focusing on Grindstones as a reward and a currency.

Both adjustments to the currency and enemy attacks made Grindstone play faster and gave the player a fairer reward for completing big chains.

Another product of constant iteration was the overarching design of the levels themselves, where the player has to reach a certain goal (either total amount of matches or enemies killed) before they could leave via a door at the top of the screen. The door is locked all the way up until you hit that goal.

Capy went back and forth on this several times, trying to figure out how to make their level endings unique. "Originally we had the idea of reaching the door, but we struggled to make that intuitive" Vader said. "Then we changed it to whenever you reach the level goal the level just ends like a traditional puzzle game. But we just liked the literal door, having to get to the door safely."

Vader said the whole idea of risk and reward, of choosing whether or not to go for more combos (or the additional goal of killing a king creep and opening a separate chest) or get out safely was always with the project. But sticking with the door as a way to end the level amplified the risk and reward factor.

"We decided to make the decision to let the player end the level," he said. "That opened the door up to a lot of interesting moments." Adding the door to the level means the player has to actually leave before they can beat a level. If they finish an objective and get stuck among increasingly hostile creeps, they could have to start over. That's at the core of what makes Grindstone so compelling.

One of the biggest challenges to designing a puzzle game with a player character on the board is how limited the player's options can end up being. Without specially-designed levels that cater to creating combos, the player could get stuck with few options at their disposal and what should be a fun experience can get frustrating quickly.

"Having the player need to calculate where they end takes this out of the more casual puzzle stage," Vader said. "Having your next move be the only consideration, especially with the creeps originally hitting in eight directions made it quite challenging."

Vader and the rest of the team did a few things to make sure the possibilities remained open for the player throughout Grindstone's 150 levels. One thing was dialing down how many different colors of creep might appear on a single level. "In terms of just balancing the levels, we added some levels with fewer variations of colors," he said. "Like you might find a level with 50 percent less of a certain color."

That change made it easier to put together longer combos. Vader said the team also adjusted how fast creeps went aggro per turn. Both options led to a more forgiving atmosphere.

As players progress throughout Grindstone they unlock various costumes and weapons that grant them additional passive and active abilities. Their designs and abilities mirror the enemies and environments you encounter throughout the game.

"One of the very early prototypes we had the single arrow, kind of similar to our delete option in [Might & Magic: Clash of Heroes]," Vader said. "You can delete an unwanted creep, we also had a sword ability that could clear the area around you, and then a jump ability if you were backed into a corner and needed to get to a different spot on the map."

"We had those locked down," he added. "We wanted the gear to make the initial objective, like killing 50 creeps, to not be the biggest challenge. Simply opening the door and clearing the room is a task most players could complete. It's when you get to the chests, crowns, and additional challenges. That's when we expanded the gear list so players could create their own playstyle as they take on a bigger challenge."

That led to weapons like the vine sword, a weapon that creates a growing vine capable of killing multiple enemies over the course of a few turns, and the ice arrow that would make aggressive creeps calm. All things to help the player continue to build big combos and something Capy has done in their previous puzzle games.

Adding a lot of weapons became a challenge to design for as the team had to make sure all weapons worked against all enemies, including the various environmental hazards from each level. The son of one developer actually created a spreadsheet and helped test every single weapon in every scenario, which still left some unexpected bugs in the end.

All these changes amounted to one satisfying gameplay system, in which if you keep making moves you'll be able to set up a large combo and build a rhythm. Some levels may be more challenging than others, but they were never too stifling. "Even when it seems like your stifled in the beginning, the tide can turn pretty quickly," Vader said. "If you keep making moves and managing the board, especially early on, it will pay off."

You May Also Like