Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Most games strive to empower the player; make them feel strong and able in a way that real life can't provide. So, how did three recent games deliver outstanding player experience by giving choices that don't matter? Spoiler Alert! Spec Ops: The Line

I recently completed Spec Ops: The Line. This wraps up a trio of games that affected me profoundly by using my own beliefs against me and handing me a story to play out. Traditionally I’ve felt that player empowerment was essential not only to great game design, but also to a great player experience. I’m supposed to be winning, successful, and grow more powerful as I progress. That’s the formula. Everyone knows that, don’t they?

Limbo

Limbo was the first to show me that this is not so. They took away my graphics, my voice, my story, and even my tutorial. I couldn’t really jump much. I didn’t become stronger or smarter or make any discernable progress as I played. I could hardly step into water without drowning. And, I had no idea what was going on in the story because, there was no story in the narrative sense. So, I slogged through the puzzles trying to figure out what was going on. But, at some point, I discovered that I could skip. The dark graphics and absence of any real music or ambient pace modifier made it seem like I should be sad, depressed. Some of the monsters and shadows trying to kill me made me think I should be afraid. It seemed to play upon the fact that we all have some fear of the dark. But, ultimately, how I interacted with Limbo and how the game affected me personally, was completely up to my own perceptions and preconceived notions.

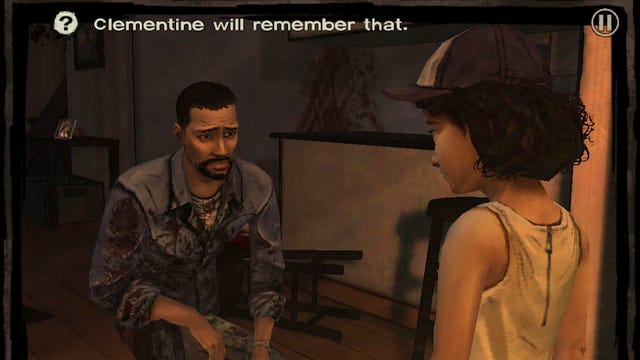

The Walking Dead

The Walking Dead: A Telltale Game Series had an even greater impact because it forced me to make choices when there were no right answers. It wasn’t like I, the player, thought I had better options, either. If you can only save one person, who do you save? How does that choice make you look to others? How do you feel about the person staring back at you in the mirror now? When you make a decision, do you filter that through your own experiences and beliefs? How do you feel about minorities? Not just prejudices--how do you feel about women as mothers or the helplessness of children? Who do you trust automatically and why? How much of yourself do you lose when you lose a wife or a child or a dear friend? If Telltale had given us power and the ability to overcome everything, we would be able to play without feeling or regret. It would just be another story we were told; more missions to complete.

I never “became” Lee. Instead, I watched his story subjectively. Like a silent member of the group, I stood by and rooted for him by choosing the actions I hoped he would take. Of course, he did those things because I told him to. But, as this observer, I also felt Kenny’s convictions, all of these mixed emotions toward Lily, a sense of pride and protection for Clementine, irritation with Duck, and suspicion toward Christa as she tried to mother Clem away from Lee. It was the first game to ever make me cry and that would not have been possible had I had the power make that world safe and provide for our most basic needs.

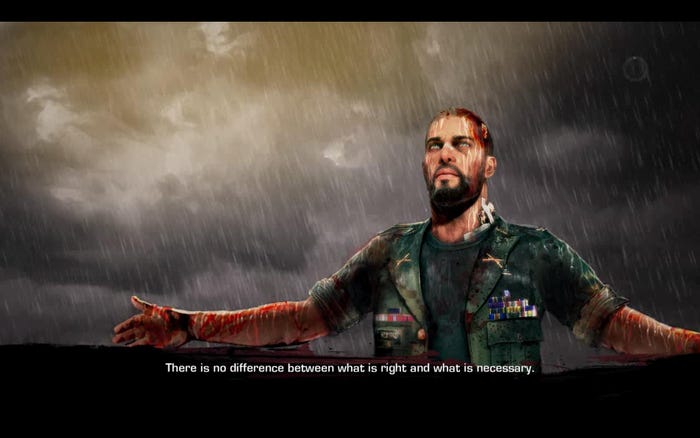

Spec Ops: The Line

Spec Ops: The Line turns our personal biases against us, both as gamers and as people. As gamers, we pick up a gun and shoot. It’s a war game; that’s what we do. How is this any different? In games like Call Of Duty and Battlefield, we enter the war assuming that we are the good guys and the people we are shooting are the enemy. Rarely do we see the collateral damage at all. When we do, for instance in Modern Warfare’s airport scene, we’re still the “good guy.” War has only two important points of time: when you wake up alive and when you go to bed at night, still whole. Everything in between is just basic survival. Spec Ops turns this principle completely on its head, especially as you reach the end. Here, again, choice is an illusion. When you are given a choice at all, it is between two equally bad options. There is no right. You can’t avoid a fight. You can’t choose not to use the white phosphorous. No matter what choices you make, the people you’re trying to save die and you have no control over that. To reinforce the consequences of your actions, the developers at Yager handicap your walk after tough scenes. You are forced to walk slowly through the aftermath, viewing the carnage and even choosing whether or not to assassinate those who have somehow managed to survive. To make matters worse, you start getting the message loud and clear--”This is all your fault.”

I didn’t take on the persona of Martin Walker and I found it interesting that, while the game affected both of us deeply, a friend and I experienced the story differently. I have deeply held convictions about the collateral damage of war. I think of places like Afghanistan and Iraq and even Northern Ireland and imagine how devastating and frightening every day life must be for the citizens there. I couldn’t help but notice the anger, frustration, and fear shown on the walls as I walked through the shambles of a previously luxurious city. I felt the horror of a child’s picture of a woman screaming as she was carried off by soldiers and understood the dilemma of cutting these people off from fresh water.

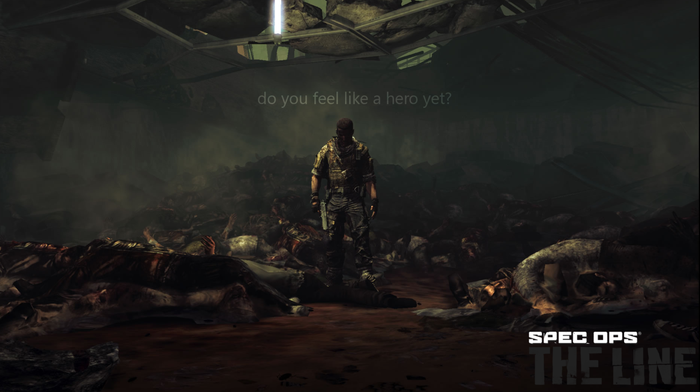

Spec Ops: The Line

My friend felt the consequences of being Walker. “The things I did in that game” he said. There was the split for me, because I felt like it was more “The things that game made me do.” In the end, the most powerful moment was hearing ‘You could have stopped at any time, but you marched on. This wasn’t what you were sent to do. You could have saved these people, but you utterly destroyed them, instead. (paraphrased)’

It’s what we do in games. We march on. Like good troopers, we complete every mission. If a studio tries to feed us a story, we cry foul because ‘that’s not a real experience.’ And, people have cried foul. Players hit the forums arguing fiercely that it didn’t matter if their choices were tough or ethical; their choices didn’t matter anyway. Yet, I believe this is the elusive point we’ve all been missing in creating real experiences...the choices mattered a great deal. They didn’t affect the outcome of the game; they are meant to be thought-provoking for the player. This is why I feel that these three games succeed where games like Indigo Prophecy and Heavy Rain failed. Both of those games empowered players to make choices that made a difference to the outcome of the game. Because the player’s choices mattered, the outcomes were just possibilities. You could go back and replay to get a different outcome. It wasn’t thought-provoking on a personal level.

Of course, there will always be players who play just to play. They put games aside and pick up new ones without allowing a story to touch them at all. I believe that, in order to actually affect our players, we need to build them experiences that they can’t control. We may also have to redefine this particular genre. After all, a game you can’t control is really just interactive cinema, is it not? This goes against every belief we hold dear in game design but, for these three games, it works.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like