Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

The role of cognitive and emotional empathy in creating immersion.

This article was originally posted on The Astronauts blog.

Story-telling games need player’s empathy to work, and yet we rarely have any discussion about it.

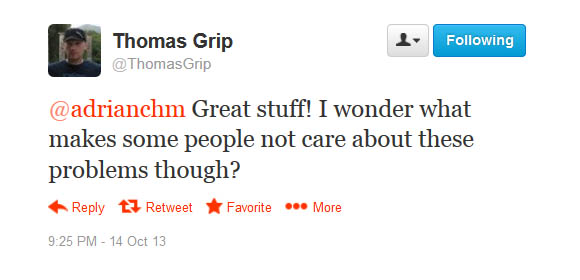

Not that I was even aware of the problem until recently. It all changed when I finished Beyond: Two Souls, posted a blog piece, and this question appeared on my Twitter feed:

It bothered me that I had no idea how to answer that, so I started to ask around and made a shocking discovery. Michal, one of the co-founders of The Astronauts and the man I trust with my life, told me he played the game for a few hours and "really liked it". Once I regained consciousness, I could not stop trying to figure out what the hell was wrong with him.

A fellow designer, Kuba Stokalski from one2tribe, pointed me in the right direction.

Empathy.

Michal and I felt a completely different kind of empathy.

This can get very complicated, or very simple. For this blog post, I choose the door number two. I feel like I am just beginning to understand the concept and how it relates to game design, so let’s make this post about the basics.

Empathy is the capacity to recognize emotions that are being experienced by another sentient or fictional being. So far, so good. Romantic comedies work because through empathy we wish those two fools finally got together at the end. And serial killers are so sadistic because they can temporarily shut off any empathy towards their victims, so torture to them is not the same as torture to us.

But here’s the kicker: there are actually two types of empathy: cognitive and emotional.

Cognitive empathy is all about deliberately understanding another’s perspective or mental state, sometimes up to a point where we fully identify with such person. Understanding why a child cries is one example of cognitive empathy (“perspective taking”) and role-playing Dragonborn is another (“fantasy”).

Emotional empathy is all about being involuntarily affected by another's emotional state. Feeling uncomfortable because a child cries is one example of such empathy (“personal distress” aka “reactive empathy”), and feeling sad and on the verge of tears when a child cries is another (“empathic concern” aka “parallel empathy”).

Remember when I said this could get complicated? Just a little tease: some people claim there’s a third kind of empathy (multi-dimensional one), and that we can also have dispositional and induced empathy, and that emotional empathy is also called affective empathy, and that…

Aw, screw it, let’s go back to simply talking about cognitive (“I understand/am that person”) and emotional (“I feel with/because of that person”) types of empathy only.

To me, story-telling games were always about me being in another world and me experiencing and feeling things through the protagonist. It was so obvious to me that I did not even look for other ways of experiencing immersion. I mean, games give me the control over the protagonist, so they surely expect me to be that person, right? If the hero of the game jumps, runs, and fires a weapon, it’s only because I did all those things, when I wanted and how I wanted – so the game must be telling me I am that person, right?

In other words, I always role-played. There’s a game to play. There’s a character to play as. Role-play. That’s how I always understood story-telling games. At least I thought I did.

As it turns out, not only I was unaware that sometimes I was actually not role-playing, but merely taking care of the flesh and blood protagonists (from “To the Moon” to “God of War”) – I was also unaware that other people can immerse themselves in story-telling games without role-playing at all. Let’s talk about the difference between role-playing and care-taking.

The way I played Frogger (not a story-telling game, really, but a good example) was always that I was the frog myself, and I tried to get to the other side unharmed. The description of my experience would include words like “Identification”, “Fear”, and “Survival”. Here’s a fragment of the “Understanding How Games Work” article from Casual Connect magazine:

Of course, experience varies from player to player, so some players may see things a bit differently. For example, rather than taking the role of the frog, players might think their role is to “help” the unlucky frog to safely reach the pond. In this case, “Identification”, “Fear” and “Survival” wouldn’t play any role in their emotional experience; these would be substituted with “Protection” instead. Here the frog is not an avatar, but it simply acts as a character the player has to save/rescue.

Why do some players believe they are the frog, while others believe they are the frog’s friend?

Empathy, of course.

The “frog” players have their cognitive empathy take over (“I am the frog, so I’d better be careful and not die”), and the “frog’s friends” have their emotional empathy take over (“Such a poor frog, I will do anything to help it”).

And exactly the same thing happens with Beyond.

In Beyond, there is at least one scene in which the adult Jodie has an opportunity to have sex with a man. In my play, that never happened. With high cognitive empathy at work, it was me who was Jodie (even though she is a female and I am a man), and I am heterosexual, so I did not go for it. But homosexual males with high cognitive empathy would not have these objections, and both hetero- and homosexual ones with emotional (instead of cognitive) empathy would have no problem with Jodie having sex. Of course, as long as they would be attracted to Jodie’s partner and feel it’s the best course of action for their journey (first case) or if they believed that Jodie herself was attracted to him and the act would make Jodie a happier person (second case).

To sum it up, in Beyond some people were Jodie, and some people were taking care of Jodie. In a game so convoluted when it comes to choices and agency, it was easier for the second group to enjoy the game, as the aforementioned choices and agency might have not been crucial to their immersion.

And then there was a third group, with people who did not give a damn about Jodie at all, and just went through the game enjoying the spectacle, but let’s leave that for later (but assume low levels of empathy of any kind).

But why do some people feel this and not the other kind of empathy when they play a video game?

This is something that is not entirely clear to me because, for better or worse, it’s not just the question of biological predispositions. Let’s start with the fact that empathy is not figured all out by psychologists, and there are many hypotheses about it floating around. On top of that, it seems that people will gravitate towards a certain type of empathy depending on their current mental state (e.g. tough day at work versus happy vacationing) – and they can even switch from one type of empathy to another within the same play session. Finish with the fact that it’s not like empathies are binary – we can feel both types at the same time at various degree of “power” – and what we end up with is one giant question mark.

But it’s not like we’re completely helpless frogs, either.

For example, it’s easier to induce emotional empathy when a game is in third person perspective. We can actually see the character we are supposed to empathize with, so we are more aware this is not “us” and thus our brain is a bit more inclined to increase the level of emotional empathy.

Another example: the more the protagonist is synced with the player’s own beliefs and desires, the smaller levels of cognitive empathy are needed to get the player immersed in the experience. If the character is mentally alienating to the player, people who cannot reach the highest levels of cognitive empathy would not be able to enjoy role-playing such character. This is why silent, amnesiac (or at least baggage-free), or player-created protagonists work so well in role-playing games.

Of course, it’s not like even if we perfectly knew how to induce this or that kind of empathy that things would magically start to work. Look at the movies. Over 100 years of theory and practice in a medium in which empathy plays a crucial role, and yet they still produce one dud after another. Knowledge is just one of the steps, but without creative talent and intuition one cannot get far.

Okay, but why would we even want to induce this or that type of empathy in the player?

Take “To the Moon” for instance. It’s probably one of the most linear games in the history of this universe, and yet it’s one of the best. When I played this game, I was deeply immersed in its world, and I laughed and cried. Looking back after learning about the types of empathy, I suspect one of the reasons why I loved the game so much was that it managed to convert the usual “cognitive empathy” me into “emotional empathy” me. And it achieved that (consciously or not) by, among other things:

a) Having at least two heroes in the story, thus making it clear that it is not about a single protagonist the player might want to immediately identify with;

b) Using a caretaker theme (look at the image above and see a) and b) there);

c) Offering non-3D second person perspective;

d) Minimizing the cognitive load through simple mechanics and UI, and thus freeing up the mental space required for empathy to exist.

By inducing strong emotional empathy, the game engaged me emotionally, and yet managed to get away with its extreme linearity. I was the caretaker (almost literally in that game), and through amazing writing and directing I cared more about what happened next rather than what I wanted to do next. And the interactivity part distinguished it from a movie by allowing me to feel like I am, indeed, a powerful force helping people achieve happiness.

The whole empathy thing is an extremely exciting discovery to me, and obviously I am merely scratching the surface here. So yeah, of course, further research, analysis and synthesis are needed – but I do think the consequences to this approach to the design of story-telling games can be profound. For me, personally, inducing cognitive empathy in the player is critical to the narrative of The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, and being aware of what works in favor of and against such type of empathy I can adjust the design of our game accordingly.

The opposite direction is okay, too. Instead of trying to induce a certain type of empathy, you may want to create a space for most of all types of empathy to work well in your game. If you, say, divide your players into five categories…

...Tamagotchi: high emotional empathy, prefers to affect the narrative either as omnipotent invisible being acting on the desires and beliefs of the protagonist or as a blank slate protagonist acting on the desires and beliefs of fleshed out NPCs. Autonomy is less important to them as long as their actions will produce results positively affecting the protagonist or NPCs.

...Writer: high cognitive empathy, can role-play anyone but it's easier for them if the protagonist is close to their beliefs, desires, and knowledge of the world, or if the protagonist is a blank slate/self-created one (will replace the protagonist with themselves); providing them with autonomy and agency is crucial, as they wish to execute on and experiment with the perspective taken.

...Distant Witness: low emotional and cognitive empathy, does not really care about emotional side of the narrative or its cohesiveness, but requires a broadly understood spectacle to maintain interest.

...Actor: anything goes, but requires relative agency and autonomy to not hurt the cognitive empathy and fleshed out protagonists or NPCs to not hurt the emotional empathy.

...Plasticine: most common type, fluid emotional and cognitive empathy that can be manipulated by the designer to the desired levels.

…then you can filter your design through such list and see how the game caters to these types of players and what is there to do if you want to broaden the game's appeal. As a mental exercise, see how Call of Duty caters to all types but Writers and partially Actors.

Finally, let me recommend a few worthy articles for further reading:

Cognitive Load and Empathy in Serious Games. Don’t worry about the “serious games” part, it seems like an odd choice of term for games focused on the immersive narrative experience. But the article will make you aware of the clash of the cognitive load and empathy, both fighting for the working memory space. It is wise not overload that buffer, so this is a pretty useful article to make one aware of the problem, and e.g. design the opening of the game – which is probably the most crucial part of any game – with the issue in mind.

Projecting the Self: Forming Empathy through Ludonarrative Mechanics. Very interesting article about a few possible techniques of inducing empathy. I especially loved the “Incomplete Information” part (another great game using it was The Witcher 2), and the most of “Player-Character Dissonance” (even though I very strongly disagree with the conclusion).

Designing Games to Foster Empathy. Another one that’s supposedly only about a specific type of interactive narrative experiences, but in reality can work for all of them. The goodies begin on page 9, where the authors propose four principles of empathy induction.

The Player and the Game. Have you ever wondered why a movie without any sentient being to empathize with would most likely be boring, but it’s not the case with video games? Answer: empathy. I kid you not, it makes a lot of sense – just read the article.

Empathy and Sympathy in Game Design. Fun little post on The Escapist forum. What’s the difference between emotional empathy and sympathy?

And then there is: Video game storytelling: The real problems and the real solutions. I and other game designers discuss various things relating to the narrative design, and empathy is one of them. I hope you will find our thoughts interesting.

Finally, I just want to make it clear that this is merely my first attempt at understanding how different types of empathy affect immersion. But I hope that this blog post inspires you to dig deeper and draw (and possibly share) your own conclusions, or at the very least that it makes us aware and take this fascinating phenomenon into consideration when designing our games.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like