Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs or learn how to Submit Your Own Blog Post

A game can either have an open world where the player can move freely, or a world that changes as the plot advances. If it has both, the player will miss out on most of the game’s content. There are some approaches to deal with this, though...

A game can either have an open world where the player can move freely, or a world that changes as the plot advances. If it has both, the player will miss out on most of the game’s content. There are some approaches to deal with this, though...

So I've been thinking about the Skyrim Problem in RPGs.

In Skyrim, pretty much the first thing you find out is that big scary dragons have returned. And the main plot is about the return of these dragons. But there's also hundreds of side-quests you can do at your leisure. Indeed, once I stumbled into the nearest village after my dragon encounter, the first things that happened to me were a quest to deliver a ring, and a nice man who wanted to teach me all about smithing daggers.

But think about your character: would they at this point care about rings or taking up a career in smithing? Might not the whole dragon thing weigh a bit more heavily on their mind?

And indeed, you can play Skyrim like this, actually taking the dragon threat seriously, moving to warn and defend people as quickly as possible. This will also mean you skip most of the game. But you can also do all the side quests, and the dragons will wait politely as you learn how to make daggers or fix people's love lives, only arriving at the maximally plot-convenient time once you decide to take back up the main quest.

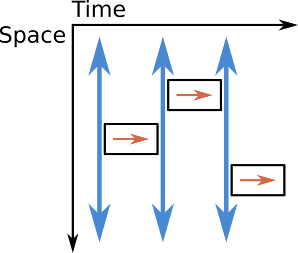

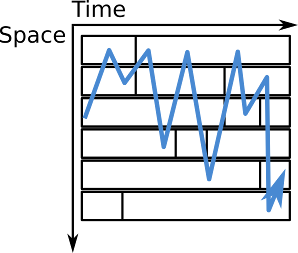

A diagram of how player movement and world time works in Skyrim. The player (blue) is able to freely move in space, but time is essentially frozen, until they go to a particular place, at which point time advances (red).

Now, some people don't mind this contradiction, but for me and a lot of others, it destroys my suspension of disbelief. It's a role-playing game, yet it wants me to play the role of a weird, endlessly distractable person whose dawdling somehow never matters.

Not all story-driven games are like this, though. Here are three ways to get around this:

Sunless Sea is a good example of this. Much like in Skyrim, you can pretty much go wherever you like and do things in any sequence. But there's no overarching main plot that would require any kind of timing.

The world isn't being menaced by dragons, nor are you in any position to fix it. There's a choice of victory conditions you can pick from, whether you want money, fame, power or something more.

But eventually, the staticness of the world does become apparent. Supposedly, all these powers are moving against one another, yet nothing ever moves. Even when you deliver a major victory for one of the factions, once the nice big "congratulations" message has passed, little or nothing changes in the world.

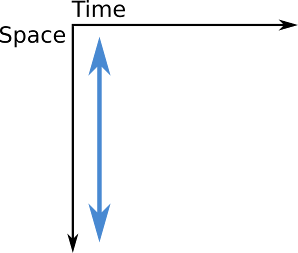

Player movement and world time in Sunless Sea. The player (blue) can move freely, but the world is (almost) entirely static. (There are a few events that permanently change the world. Unlike in Skyrim, these can be done in any order.)

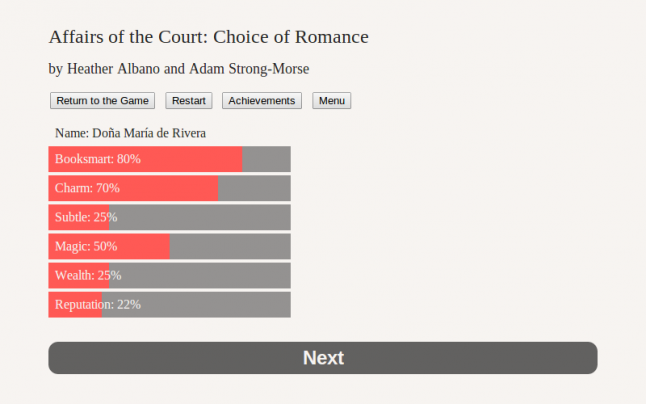

Choice of Games has done some excellent work with games that are mostly linear sequences - with some deviations, but no loops - that nevertheless let the players make meaningful decisions. While the player has little or no input on where they're going, their decisions end up changing stats and flags that do end up mattering down the line.

Player movement and world time a Choice of Games title. The player has little or no control over where to go, and is moved through the story in a fixed path (red). There are a few variations of the path depending on choices or stats, and the story usually branches heavily right at the end, but the player can't decide to stay in one place in the timeline.

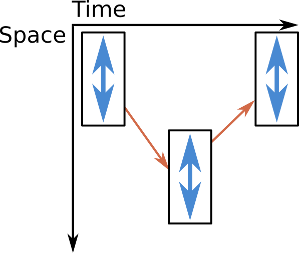

Deus Ex, or more recently the Dishonored games, use this approach. The levels are large and allow for plenty of free movement and different player actions, but once one level is done, the game permanently moves on to the next one.

The staticness of the levels matters less, because you only spend a few hours there at most. You can spend ten real-time days in the first level of Deus Ex, and dawn never comes. So the game alternates between giving the player free movement and letting the game's timeline advance.

Player movement and world time in Deus Ex. The game alternates between large open-world-like levels with free player movement (blue) but no time passing, and fixed timeline progression between the levels (red).

We need to either restrict the player's ability to move in the world, or the world's ability to progress on its own.

If the player can go wherever they like, and the world moves on its own, this means the player will miss most of the content. Instead of a one-dimensional list of places or times, it's a two-dimensional field of places x times through which the player will take a linear path. This means that most of the work that went into the game will not be touched upon in a playthrough. Which in turn means that the game will take a lot of effort to make compared to the experience it delivers.

The Deus Ex approach of a linear sequence of open worlds is a compromise solution. But it also doubly constrains what can happen - the player cannot roam as freely as in a single open world, and the story still needs to be pretty much linear. Indeed, the original Deus Ex has a completely fixed story throughout, until a final massive decision for the player.

Choice of Games does this to soften its restriction of player movement. While you can't decide the order in which things happen, you can still make choices within these events that end up influencing what events happen in the future, or what their outcomes are.

Dishonored tracks exactly one stat, the chaos rating, that changes the levels and the final outcome somewhat.

So, encoding the player's choices or the world's progression through time as stats reduces the field of events back down to a one-dimensional list while allowing for some controlled degree of variation. Events can be swapped out entirely or modified in their details on the basis of the stats, making for a more reactive world.

You can even encode everything as stats, both the player's choices and the world's progression. Now, events are picked from a pool based on the stats. This makes for a simulation-esque game that nevertheless has hand-written content. The King of Chicago pioneered this approach.

The main problem here is that it's very possible that some events will keep happening, while other events never happen.

Much like above, a play-through is a linear path through a space of player and world stats. Ideally this path will touch a large proportion of the possible events exactly once. If it keeps coming to the same place, the story will be repetitive, and if it goes past most of the events without touching them, there's a lot of wasted effort.

So what are some concrete possibilities to push the envelope while avoiding wasted effort and the Skyrim Problem?

A bunch of different stats that modify but not replace each sandbox level could make the world more reactive to the player's decisions without breaking the bank.

To do this right, the passage of time should not close off opportunities for the player in frustrating ways. And to do it efficiently, most of the time, the passage of time should change details rather than requiring multiple versions of the same content to be created.

A variant on Sunless Sea's static world. The player can move freely, but as they move, time slowly advances and various parts of the world change. Each location may have 1-3 versions that appear over time.

Finally, by gently controlling a playthrough's movement through the space of stats and careful placement of events that can change their details based on stats, a game can let stat changes encode both player choices and the passage of time without becoming repetitive or wasteful.

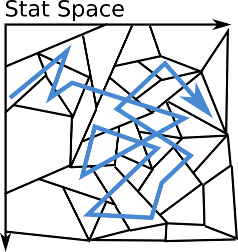

Picking events based on game stats. Note that the dimensions are no longer time and space. Rather, this is a 2D representation of a high-dimensional space of stats. A playthrough is a complex path through this space, and the events that happen are picked on the basis of the current stats.

So what's the conclusion? Free player movement in a non-static world inevitably leads to a lot of unseen content. Obviously constraining player movement or making the world static makes games feel less alive. To ameliorate this, constrain player movement in subtle ways, don't change the world too much, and use stats to change things without having to completely rewrite them.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsYou May Also Like