Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What lies behind completionism and why it is more than just some players' funny attitude towards gaming.

Which road? (Photo by Burst on Unsplash.)

When it comes to a book or a film, there is only one path to experience it: we start at the beginning and finish at the end.

This doesn’t mean there is only one storyline. Neither does it mean the story is told in chronological order. What it means is, in a book or a film, there are no choices, no branching, and no randomness—there may be for the characters, but not for the reader or viewer. As a consequence, we get to see all the content in one go. Nothing gets left out.

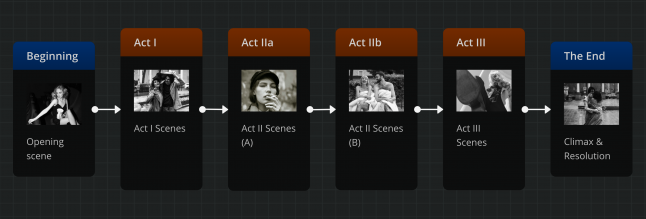

The archetypal structure of a film’s story as a linear diagram. (Note: all diagrams in the article are made with Arcweave.)

Games on the other hand offer choices, branching narrative, randomness, and often multiple endings. Not only do we get to choose, but we also get to miss out on huge parts of the content!

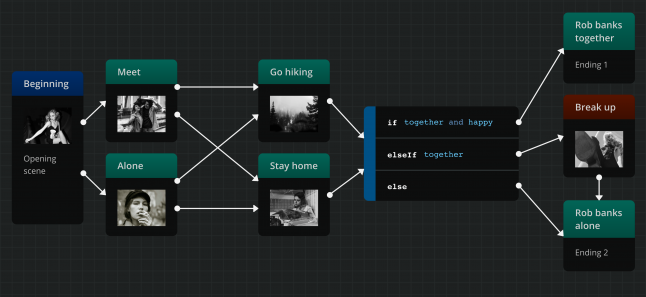

In interactive narrative, the structure hardly stays linear. Instead, various plot formations are created, like branches and bottlenecks.

This structure creates an extra tension to the player: “is there more that I haven’t experienced?” And this is a compelling part of the allure games have.

Too compelling, perhaps. Some people simply want to see everything. Completionism is the compulsion to go after every objective in a game. It goes beyond the hedonism of wanting to leave no virtual stone unturned and reaches OCD levels of… wanting to leave no virtual stone unturned.

Although usually referred to as a compulsion towards collecting game achievements, completionism is used in this article in a broader sense.

Let’s accept that there is a tendency towards completing tasks and different people have it to different degrees.

Is this tendency something skin-deep or the tip of some mysterious iceberg that reaches unexplored depths of our existential angst?

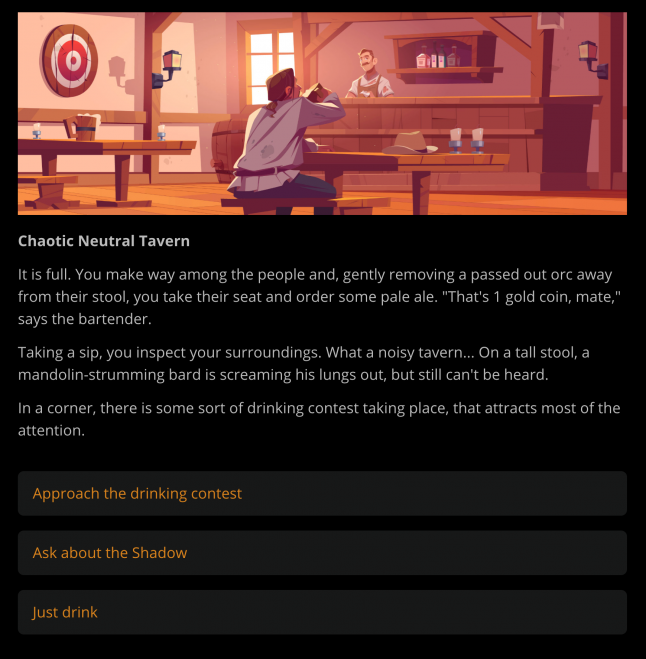

To help you audit (or celebrate) your degree of completionism, I created a little on-line game as a companion to this article. I wrote it on Arcweave and you can freely play it on your browser—you will find the link at the end of this post.

Don’t get confused: wanting to replay a game does not make you a completionist. Few players will settle for what just one playthrough has to offer and the average gamer will replay a high-replayability game.

What the average gamer won’t do, though, is insist and grind. Complete all the sidequests. Collect all the badges. Unlock all the features. Discover all the easter eggs.

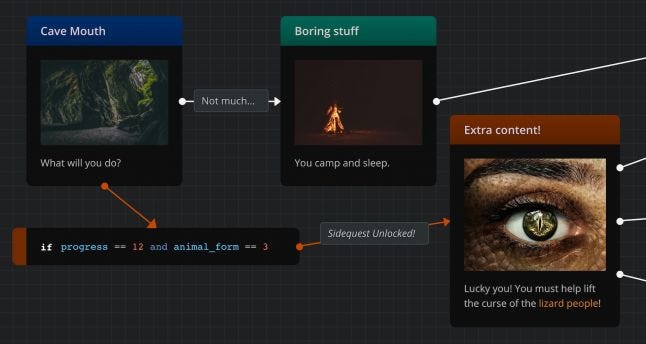

Easter egg content gets unlocked only if very specific conditions are satisfied.

So let’s explore the spectrum of this human tendency to complete things.

The first type of player dwells at the outskirts of the spectrum. They won’t sweat much over achieving goals or optimising their process—unless their goal is to enjoy themselves.

Casual players show the least amount of completionist behaviour. This doesn’t mean they won’t play a game twice, rather that their approach to gaming has no compulsion. Also, “casual” doesn’t mean they don’t care. They may very well have the desire to finish the game, but their desire to have fun is more important to them. They refuse to jeopardise it, even if it means they’ll have to abandon the game altogether.

Those players either have this as a natural state or they have grown into it, through overcoming compulsions like completionism itself.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves.

The second type is also positioned at the outskirts of the spectrum. They play the game with curiosity and interest, but their strong boundaries stop them from overinvesting. They know their limits in time and energy—and are determined to respect them.

Perhaps they have a soft spot they are fully aware of: a proneness to binge-playing—even to completionism itself—if they let themselves.

So they don’t. And if they do, their two natures fight each other, often resulting in self-punishment: “I shouldn’t have stayed up all night…”

The calculating player is clearly inside the spectrum of completionism, but quite far from the centre. For them, the most important reason they replay a game is to get their money’s worth.

Their gaming experience feels like a financial transaction. Their motto is “Missed Content Is Wasted Content.” The question they ask themselves upon finishing a game is “Did I break even?”

I’m not judging this approach. Games are expensive and nobody wants to waste money. All I’m saying is this: compulsively completing a game just to get our money’s worth isn’t the best way to enjoy ourselves.

This is a very particular case of player. It is the person who studies games because they want to know their mechanics. They will not grind to boost their stats, but to see “How many times can I try this before responses start getting repetitive?”

They design games themselves, so part of their job is analysing them. Learning how things work under the hood.

The craftsperson must play and replay. The must see if an outcome is random or based on some algorithm. See what always happens and what varies with each playthrough. Speculate how something works. Go back and try different paths. Do silly things, just to see if the designers have predicted such player behaviour.

Image by vectorpocket on Freepik.

This type is at the centre of the spectrum. They simply don’t want to miss out on any part of a game’s content: easter eggs, hidden equipment, impossible score points—things that a casual player won’t come across with a casual playthrough.

For this type, it has nothing to do with money or craft. This is where completionism manifests itself as an irresistible compulsion.

The reason behind it? Fear of Death and Fear of Missing Out.

What? Don’t you believe me?

Why play games compulsively? It must have to do with the question, “Why play games at all?” What is the deeper reason we do it in the first place?

Life is very much like games. It is full of pleasant and painful events. It offers opportunities and choices.

But there is a huge difference: life doesn’t have UNDO, RESTORE, or RESTART. We can’t SAVE. We can’t go back and replay a part where we messed up.

In life, we can’t raise the dead.

On the other hand, in games, reincarnation is easy. We can just RESTART. And because even restarting is a painful process, we can also SAVE and RESTORE.

This privilege of virtual reincarnation is one of the deeper reasons we are so into gaming. Playing games, on a deeper level, is a way to experience immortality—and a fun one, that is.

Choosing is hard. Choosing one thing means losing another. Robert Frost’s poem The Road Not Taken begins with the grief of a traveller who couldn’t be in two places at the same time:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And sometimes it’s more than two. An open-world game seems to have infinite possibilities.

Like life.

After choosing an option, a part of us has the fun, while another part laments the roads not taken. “What about the other option? Would the grass be greener over there?”

Missing out can cause distress. It evokes the primal fear of loss—even the fear of death itself.

Missing out on a story’s content doesn’t sound like a major reason for grief. Still, it can be big enough to trigger compulsive attempts to regain control—enter completionism.

Like double-checking the stove is off, the pure completionist will grind and exhaustively explore a level’s geography, seeking feelings of safety and comfort.

When it comes to choice, completionism is the manifestation of our desire to both have the cake and eat it. Only games can offer us this privilege.

Why say no to that?

We don’t actually have to say no to anything, if it works and gives us joy. The problem with completionism is it usually takes away much of the joy of gaming. An online search for the term “completionism” leads to gaming forum threads, where players confess their lack of enjoyment.

Is completionism a curse? Are completionism and fun mutually exclusive? The more we position ourselves towards the spectrum’s centre, the more often the answer seems to be a yes.

Let’s get back to choice, for a moment. We already mentioned that choosing is hard, but we need to get more specific.

Which choice is easier, between two or among multiple options? In his book The Paradox of Choice American psychologist Barry Schwartz argues that more options create more distress. Fair enough.

What if our multitude of options becomes an infinity, though? Does having practically infinite options cause bigger distress? Or could it perhaps be the key to freeing oneself from the compulsion to see Everything?

It sounds like a paradox, but think about it: it is easier to complete a choice-based game than an open-world one. Therefore, here’s a theory:

The more open the world of a game is, the easier it is to let go of seeing Everything in it.

Then, how about a case where “infinity” isn’t just a figure of speech? In No Man’s Sky, AI algorithms create content upon the player’s arrival. Every time we play the game, even in the same location, the content will be different.

This is a very unexpected interpretation of Antonio Machado’s poem Caminante, No Hay Camino:

Traveller, there is no path.

We create the path by walking.

Do unlimited possibilities really make things more difficult for completionists or could they be part of healing their compulsion? As one former gaming completionist confesses:

No Man’s Sky has a literal endless amount of content to explore… and in a way, that was freeing. There’s a specific ending to the story, sort of, but having an infinite amount of planets to explore meant that my brain stopped caring about it after a while and I could just focus on enjoying the game.

Perhaps more is indeed less, but perhaps we need to go through unbearably rich quantities of content, before we realise how much we can simply let go of. As William Blake writes in his Marriage of Heaven and Hell:

The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.

Enjoyment of any kind requires some wisdom, after all.

Like other compulsive behaviours—and regardless of its degree—completionism has deep roots, watering itself from our most primal fears, like fear of loss and fear of death. Therefore, it is not to be lightheartedly dismissed as some players’ funny attitude towards gaming.

On the other hand, completionism—like perfectionism and competitiveness—is likely to hinder our gaming enjoyment.

The key is letting go of our desire to see everything. Coming to terms with missing out on the road not taken.

And focusing on the fun found along the taken one.

As stated in the introduction, this article comes with a a little treat: a companion game I made on Arcweave. It is a short prototype featuring a main quest along with a few side-quests.

You can play it on your browser for free. If you do, I would love to hear from you—maybe even receive a screenshot of its final screen, showing which quests you followed and which ones you skipped. Did you feel like following all of them?

Arcweave makes it very easy to create and run such game prototypes. (You can see this one’s structure here.) If you want to quickly learn how to make them yourself, watch Arcweave’s basic tutorial series on YouTube.

–

Giannis Georgiou is a writer and story consultant focusing on subjects of narrative structure, theory, and technique. He is content writer in Arcweave.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like