Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"VR feels like a mansion full of unopened doors. And behind one of those doors is an undiscovered language of storytelling; an entirely new narrative structure specific to VR."

The Gamasutra Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including maintaining player tension levels in Nex Machina, achieving seamless branching in Watch Dogs 2’s Invasion of Privacy missions, and creating the intricate level design of Dishonored 2's Clockwork Mansion.

I’m Rob Yescombe, freelance writer and narrative director. Lately, I’ve been lucky enough to collaborate with Tequila Works on both Rime and our VR murder mystery, The Invisible Hours. Over the last 13 years, I’ve worked on franchises like Star Wars, Alien, Crysis, Family Guy, The Division and Blade Runner. But my heart is in virtual reality – this year, I also wrote the PSVR titles How We Soar and Farpoint.

Here’s why I’m so excited about VR: it feels like a mansion full of unopened doors. And behind one of those doors is an undiscovered language of storytelling; an entirely new narrative structure specific to VR.

Our dream with The Invisible Hours was to try to open that door.

Your life story feels simple when you’re inside it. Downright obvious, even. But when you try to replicate its structure inside VR, things get complicated – fast. But that’s what we set out to do: to mimic the narrative structure of real life.

In real life, each of us is the protagonist of our story. And yet, at the exact same moment in time, we are also supporting and background characters in each other’s stories – we play all these roles simultaneously, and none of our stories can exist without the other. We are each a single thread in a tangled web of interdependent narrative.

The Invisible Hours is an Agatha Christie style murder mystery that takes place in a mansion over one hour – but with seven suspects, that means seven hours of narrative interwoven within that single hour. So, for example, if you follow a suspect up to the attic, you’ll be missing multiple other scenes happening at that exact same moment elsewhere in the mansion. The story is always alive, whether you’re looking or not, just like real life.

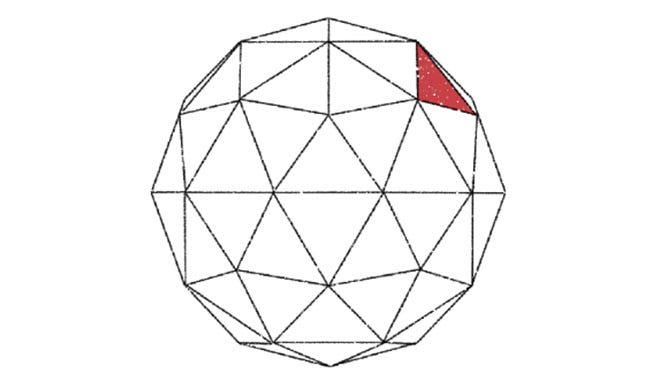

We call this story structure ‘Spherical Narrative’.

The Invisible Hours is built out of dozens of motion captured scenes that all have to begin and end at different times – but must all fit together into one giant sphere of uninterrupted story.

But that’s not the hard part.

Before you can even begin, Spherical Narrative is trapped inside a paradox: you have to know how long every single scene is going to be – to the exact second – before you write it, because the length of every scene is dependent on the length of all the others.

In an attempt to crack this paradox, I started by writing a scene-by-scene outline from each character's perspective on their individual story, then placed them into a grid representing units of time. At this point they may look synchronized, but not only are the varying lengths of every scene a consideration in synchronization, we must also apply the unique distances that characters need to traverse between their scenes in varying locations, the speed at which they need to cover those distances, and the impact those factors will have on the scenes that they are traveling to interrupt. If any one of those puzzle pieces is off by a single second, the whole thing breaks. But now, imagine multiplying that problem across dozens of scenes, across five floors in the mansion, across seven interwoven stories.

However, with this very rough view of the story, we could start to design 2D floorplans based on the spatial and dramatic requirements described in the outline. We knew we were going to need a very flexible environment layout, to help insure against human error later down the line – so that meant additional rooms and multiple routes into each space of the mansion – but it also needed to feel believable and accurate; this is a real-world setting after all.

We tested about thirty 2D layouts against the outline. This gave us a broad sense of what was required, but it couldn’t give us the specificity we needed to progress. The final layout of the mansion is dependent on knowing where scenes will take place, how long they will take, and how far and fast each character will walk between them.

You can’t finalize any of those things until you have a script – but you can’t write the script without already knowing them. Ultimately, I had to set myself specific times for every scene and plan to stick to them, no matter what.

Once I committed to all those times, we could build a 3D animatic around it. Keep in mind that we still don’t have a script at this point. This was a definite risk, and perhaps if this was not an independent production we might not have been allowed to take that risk.

Now knowing the location and length of every scene, we could build a whitebox and extrapolate in an animatic the routes and speeds of each character. There were a handful of layout tweaks here, but generally what we planned in 2D stayed put.

With the animatic complete, I could start on the scripts proper – knowing the exact time limits I had set myself for every moment of every scene.

The on-paper version of Spherical Narrative is challenging enough – but putting it into actual production is where things really get complicated.

Every piece of this spherical jigsaw needs to fit together precisely. If even one scene runs a few seconds long (or short) it has a huge impact on everything that follows – across every story thread. If this was live theatre, one actor arriving a few seconds late into a scene is no big deal – the rest of the cast can 'fill' and improvise while they wait; but here we have seven hours of scripted animation. That flexibility and margin for error simply does not exist.

With so many time dependencies, the chances of things going awry were incredibly high. So we knew we had to find ways to protect ourselves. And as a low budget production, we couldn’t risk going to the mo-cap shoot unprepared in any way.

To tackle this, we spent a full month rehearsing every single scene against a stopwatch. A logical thing to do in principle, but there is also a very high risk when rehearsing this intensely, that the humanity is driven out of the actors’ performances. So, I spent significant time doing deep character exercises with the cast to maintain a balance between efficiency and emotion. But again, a leap of faith was necessary here: we drilled scenes until they were within a four second margin, and trusted that we could tighten the gaps on the shoot itself.

For the shoot itself, we opted for traditional facial and motion capture. Even though we didn’t want to edit motion within the scenes themselves, we knew that adjustments to traversal speeds could save (or add) a few seconds between scenes if we got into a bind.

On the shoot, we had to track data very, very carefully: the project amounts to an unprecedented 2,240,000 frames of character data in Motion Builder. As such, it proved to be one of the most complex motion capture shoots in videogame history. But once processed, it was a relatively conventional pipeline to assemble the data inside the engine.

But ultimately, all of this planning and mathematical effort has been in pursuit of a narrative naturalism inside VR – it really does feel ‘alive’ when you’re inside it. We’re proud of what we built, and we really hope other devs will try Spherical Narrative for themselves.

You May Also Like