Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In the latest in his popular Game Design Essentials series, writer John Harris examines 10 games from the Western computer RPG (CRPG) tradition and 10 from the Japanese console RPG (JRPG) tradition, to figure out what exactly makes them tick -- and why you should care.

[In the latest in his popular Game Design Essentials series, which has previously spanned subjects from Atari games through 'mysterious games', 'open world games', 'unusual control schemes' and 'difficult games', writer John Harris examines 10 games from the Western computer RPG (CRPG) tradition and 10 from the Japanese console RPG (JRPG) tradition, to figure out what exactly makes them tick -- and why you should care.]

Designed by: Gary Gygax, Dave Arneson

Influenced by: Braunstein, a game that Dave Arneson is known to have played, predated D&D. There were also weird fiction and pulp fantasy stories and tabletop war games dating back to H.G. Wells' floor game Little Wars.

Series: No less than seven editions and many side-products. Not to mention all the CRPGs that claim to be derived from its rules. Also, those CRPGs that steal mechanics from it without attributing them.

Legacy: Nearly all RPGs.

Although it's not a CRPG, let's begin with a discussion of the original role-playing game, the edition of Dungeons & Dragons that started the role-playing game craze in 1974. It might not seem relevant to the discussion, but there are some things about the RPG genre that only really make sense when viewed in comparison with this particular game.

It may not actually have been the first role-playing game; word is that Dave Arneson participated in another game prior to its release. But D&D 1974, referred to among fans on the 'net as "OD&D," was the introduction of RPGs to practically everyone else.

First: the term "role-playing game," it seems, was not used in the original set. A search through the books and supplements of the OD&D game show a good number of uses of the word "role," as a general term for a character played by either a player or the referee, but none for "role-playing game." Neither is it used in any of the supplements.

The earliest published use seems to be either the Holmes version of the game, which slightly predates AD&D, or the last issue of TSR's early publication The Strategic Review, where it's used in describing their shiny upcoming magazine The Dragon. Until then, it seems there may have been no good name for what Dungeons & Dragons was.

This is important because "role-playing game" is one of those terms that is proscriptive in its use. It implies that players, to an extent, personify their characters. D&D arose out of a marriage between wargaming and fantasy fiction, so narrative is in its blood, but early on the most frequent type of adventure was a simple free-form dungeon crawl. If you count OD&D as a role-playing game, then you necessarily have to admit that RPGs don't have to be games of storytelling, or at least not games of "top-down," DM-driven storytelling. (RPGs have always been games of what we might call "storywriting".)

In this sense computer versions have more in common with early social roleplaying sessions than later ones. Few people play CRPGs with an eye towards acting out their characters' roles.

Second thing, the game was hard. Really hard! Characters dropped like flies! Only a small percentage of characters would ever reach level two. That might seem harsh, because it was, but it didn't chase players off because people didn't identify as strongly with characters. One tends not to get attached to characters who stand a good chance of not making it out of their first trip into the dungeon. Without storytelling, and with the game's much-simpler system -- compared, even, to AD&D 1st edition, which is not really all that dissimilar to OD&D with all the supplements applied.

This is important because many early CRPGs, and even some early JRPGs, took a similar attitude to character death. The Wizardry-influenced style of game makes death common, especially at low levels. Wizardry charges a good deal to revive a dead character, the process has a good chance of failing, and if it does it costs even more to try to revive the pile of ashes the corpse becomes. The roguelike genre continues to hold up the tradition to this day.

Third thing, the game had a strong setting and a reduced scope. OD&D is a game about exploring dungeons, and other dangerous places, and that's mostly it. High-level characters may get the opportunity to start their own little fortress or tower, but with level nine, "name level," so far away and the game so deadly, this isn't something a player can do more than hope to reach. Because dungeon exploring is ultimately a loot-harvesting game, and treasure can be obtained in ways other than fighting, characters gained one experience point per gold piece acquired. This knowledge can seem surprising to us computer gamers today, as nearly every CRPG that uses an experience system anymore doles it for fighting alone.

The XP-for-gold rule implies strongly that the DM must carefully guard his riches and not hand out gold on a whim. This need led, at times, to a kind of DM vs. players rivalry. If a DMs failed to realize this they could end up subtly nudged towards giving out extra wealth, leading to what became known as "Monty Haul" campaigns, with vast amounts of treasure distributed for little work. Second edition remedied this by switching to all combat-based experience, offering treasure XP as an option, as well as XP for completing quests.

Handing out experience points for collecting gold fits in with the '20s and '30s pulp fantasy works that inspired the game, which are fairly gritty tales with heroes are mostly in it for personal enrichment. Characters in pulp fantasy are, by D&D standards, fairly weak. Even the most powerful ones, like Conan, face significant danger from some angle or another, in his case from magic and gods. OD&D characters are never completely safe, at least not if the DM is competent.

So, why is this important? Because this attitude, that role playing is a game of loot acquisition first, is everywhere in early computer RPGs. Even those with strong save-the-world quests have a lot of loot gaining along the way. It also explains those "strange" games, like PLATO dnd, that allow characters experience, or even direct improvement, for the simple act of money-harvesting.

Fourth thing: OD&D did not include a mandatory combat system. The first books referred players to Chainmail, a prior game of Gygax's, for ideas for how to resolve battles. It had a section marked "Alternate Combat System" that would later become the standard combat mechanism D&D would use for years, but Chainmail was the official solution, and besides its use of armor class and hit points, its rules were quite different from what is now seen as standard D&D combat.

This is important because it shows is that combat play, ultimately, was not considered the defining aspect of the game. It was a replaceable system. When played with Chainmail, D&D looks a lot like a special form of wargame campaign. This may well be a contributing factor to the strong split between "exploration mode" and "combat mode" that many RPGs use to this day. OD&D didn't get the system that would ultimately become the combat method used in AD&D 1st edition, and later mutated into the "d20 System," until the first supplement, under the heading "ALTERNATIVE COMBAT SYSTEM."

Related to this is the fifth thing, and perhaps the most important of all: OD&D was poorly explained. It is impossible to play Original Dungeons & Dragons with just the first three rule books, and even the supplements left important things out. Gygax and Arneson wrote for a presumed audience of wargamers. It still managed to become popular because the game primarily spread by word-of-mouth. People didn't learn from reading the books; they learned from other people, and thus the rules of the game followed the principles of oral tradition, with the rules used as reference.

This is important because it let a hundred rulesets thrive. Different regions tended to play the game in different ways. When more rigorous rules were written, some people decided they liked their old system better and invented competing RPGs, codifying those rules, to compete with D&D. It is this very proliferation of rules that produced the wide variety of games and approaches among early CRPGs.

I am not trying to argue that the game was better or worse than present-day RPGs. It is not hard, really, to find people who would say otherwise; there is a burgeoning field of "retro-clone" RPGs out there whose purpose is to make games very much like those old systems. But the original game of Dungeons & Dragons was surprisingly different from what we remember today, and it turns out that many of the oddnesses of RPG gaming, some persisting right up to the present, have their roots in its evolution.

Some of the ideas for this introduction came from the following blogs:

- Delta's D&D Hotspot

- Jeff's Gameblog

- I Waste the Buddha With My Crossbow

- RetroRoleplaying

- Lamentations of the Flame Princess

- Grognardia

- Always Go Right

Designed by: Andrew C. Greenburg, Robert Woodhead (original designers, creators), others

Influenced by: D&D, PLATO RPGs

Series: Eight games, the last one a critically-acclaimed 3D extravaganza. In addition to these, a surprisingly large number more were made in Japan.

Legacy: The Bard's Tale series, Might & Magic, AD&D Gold Box games and more. Inspired an entire category of grid-based 3D RPGs, out of favor now but still, if you know where to look, around. The Etrian Odyssey games for the Nintendo DS owe a lot to Wizardry.

This article focuses on the early Wizardry games, which are distinctive enough to be the style of play most people think of today when they consider the series.

Wizardry is not the first CRPG; there were a number of earlier games. It isn't the first 3D-view, step-based dungeon crawl RPG either; there are older games for the PLATO multiuser system that look a fair bit like Wizardry. The game Oubliette is similar, down to sharing many of the same spell names.

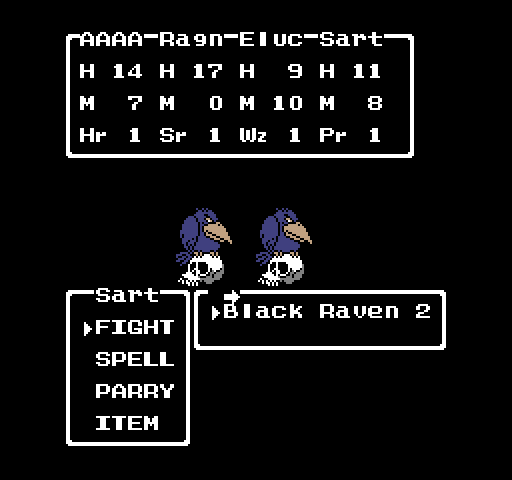

The key unit of game content in Wizardry is the encounter, a scripted event that occurs when the player's party enters a particular square. Some encounters are monsters, which can be either friendly or hostile. Some are treasure chests. Some are deadly traps. Some are special devices that are manipulated through menus. Some are NPCs that provide information, or ask questions, or might attack.

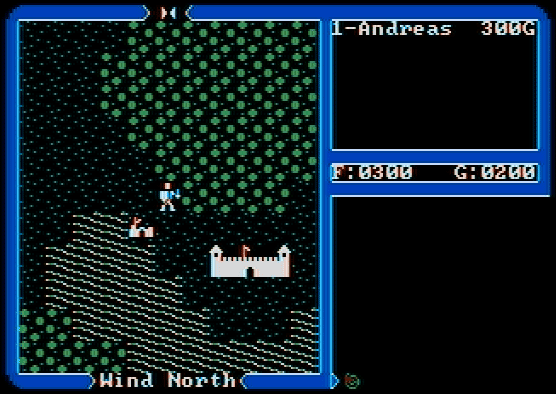

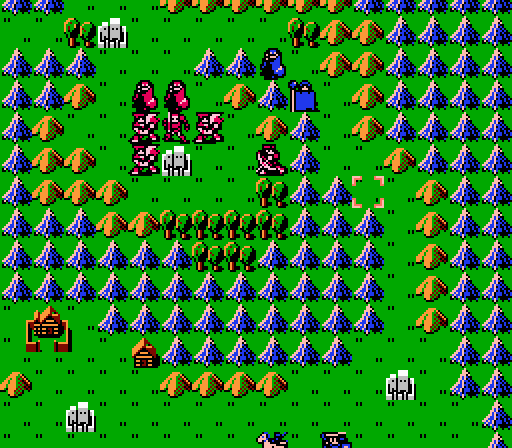

Wizardry (Screenshot courtesy http://www.gamingwithchildren.com/)

There are set encounters, which occur when a specific spot is entered, and there are random encounters, which have a slim chance of occurring whenever the player enters a square within some region. Encounters, when they happen, may have a graphic tied to them but in nature are textual events, relayed to the player using narrative and asking him to make a menu choice in response.

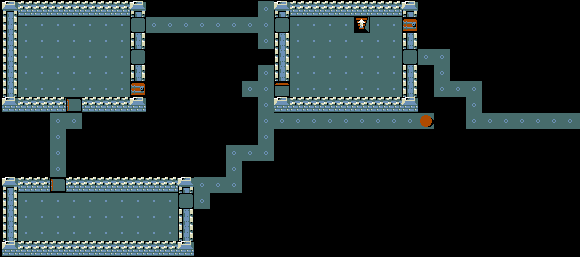

Encounters are housed on a dungeon map, a region of maze laid out along the lines of a grid. The grid itself is not shown on-screen; instead, the player's perspective is shown as if standing in the maze, facing either north, south, east or west. A simple algorithm, much-used in RPGs of the time, is used to render the walls and corridors in the party's sight.

The grid-based layout of the dungeon and atomic, space-by-space nature of the party's movement combine to make rendering relatively easy to implement; this is how Wizardry was able to present a 3D world to players a decade before Wolfenstein 3D. It was much copied, to the extent that it shows up in some far-flung products: the original Phantasy Star uses a much more attractive implementation for its 3D dungeons; retro action games like Fester's Quest and Golgo 13 also implement their own takes.

The 3D effect makes mapping essential. The grid layout both makes mapping easier, by conforming it to a grid, and harder, by making it easier to trick the player using map gimmicks to fool him into mapping incorrectly. (Mapping tricks are explicitly mentioned on the OD&D books as a useful tool for the DM, so blame them.) One such type of trick, a particularly mean one, is the teleporter, which invisibly sends the player to another spot in the maze, sometimes one that looks similar, but not identical, to the previous one.

Another cruel gimmick is the spinner, which randomly flips the player's facing direction to a random direction upon entering. If the player didn't notice that his facing has changed, a spinner can easily mess up an entire map. Wizardry even has dark areas that provide no vision of the corridor ahead, requiring that the player deduce where the walls are solely though the "Ouch!" messages that appear when the party collides with one. These tricks make coming up with an accurate map one of the biggest challenges of the game, and as a result it's rather satisfying to finish out an entire level.

Of all the games listed here, none is as inseparable from the act of mapping as Wizardry. An automapping feature would arguably ruin the game, because it'd reveal information, such as having been teleported or spun around, that players are supposed to deduce for themselves. Many players now would view that as being screwed with and abandon the game, but it's important to remember that being screwed with, and overcoming it, is one of the great joys of classic Dungeons & Dragons.

Even though there are many scripted encounters, or "specials," a key difference between Wizardry and the D&D sessions it seeks to emulate is the absence of a flexible DM to allow the players to try things that aren't offered in the basic ruleset. There is no jumping up on tables, swinging from ropes, prodding with 10-foot poles, knocking on walls, or listening at doors or using them to block pursuers. Monsters don't exist until they have been triggered, and once a fight begins it takes place entirely in that square of dungeon map, and cannot sprawl out into the dungeon.

It is important to note that, in the 25-plus years since Wizardry was released, no CRPG has satisfactorily addressed this limitation, that of system inflexibilty. The lack of verisimilitude remains the most grievous difference between them and pen-and-paper games.

Wizardry's dungeons feel more in line with the D&D archetype than has been in vogue in more recent times. It casts the dungeon as bizarre magic place where things don't always make sense. The player has no way to determine what's in there before he enters it, unless told by another character. If the player explores every space of the dungeon but the one with the essential object in it, then he'll still have no hint that it exists. This is usually partly countered by dungeon design: a 3 x 3 room with a door will have its relevant encounter placed by the door so as to provide the illusion that it fills the space.

One thing about these early RPGs is that it's much easier to get them into an entirely unwinnable state than in more recent games. A dead low-level Wizardry character can only be revived by paying at the temple, and that costs good money. This is entirely in line with early D&D, where a hopeless case can be simply re-rolled, and indeed this can be done in Wizardry too, generating a new character to replace the dead old one. This idea is nearly alien in later games, but still shows up in weird places; one of the best Dragon Quest games is the third installment, which isn't so easy to make unwinnable—but still has this sort of replaceable character system.

A consequence of the system is the failed game, a way that a game of Wizardry, and some Wizardry-like games, can actually be lost. It's possible for your whole party to die, and be so low on money that they cannot be revived. This state is most common at the beginning of games, and often it'll take a player several attempts before he is able to get a group of characters to a survivable level.

Wizardry is hard—almost as hard as early OD&D and AD&D. Wizardry, however, provides the player with a way around this through its use of saved games. In D&D, players are not supposed to go back to prior states of the game. If everyone agreed to there's nothing to say they couldn't, but they don't. This aspect of simulationism has never left pen-and-paper RPGs, even those that don't try to simulate anything pose irreversible choices, primarily because, with multiple players involved, it's unfair to the other participants to back up for one's convenience. But the effect is more profound than you might suspect; the ability to save and load games makes CRPGs allows those games to subtly focus on exploring multiple branches of the game's probability-space, instead of going down a single path.

Designed by: Richard Garriott (main designer, creator)

Influenced by: Difficult to say. Definitely D&D, but the dungeon exploration mode looks too much like the PLATO/Wizardry system to be accidental, although it's possible the algorithm was independently-derived.

Series: Nine "core" games were made by Origin, but Ultima VII had a couple of large expansions that are by all rights games in themselves, there's a still-extant MMORPG, and there are several other side-games made by them. Japan has a couple more games, the Runes of Virtue sub-series.

Legacy: The Ultima series is the forefather of the vast main category of CRPGs.

Wizardry didn't change much among the majority of its lifespan, but the Ultima games changed greatly during their early years. This article is mostly concerned with the earlier games, but the flow of its design can be traced up as far as Ultima VII, generally regarded as the zenith of the series' popularity and influence.

The first games (technically the first Ultima game was Akalabeth) were dungeon-crawly things, but without the benefit of Wizardry's many specials or mapping tricks. Dungeons were primarily just places with monsters, and the occasional important plot item. They tend to be less interesting places than Wizardry's treacherous dungeons.

That's okay however, for Ultima brought us what has become known as an "overworld," a tile-based world in which the dungeons are set as special locations. It also brought us real towns, and a routine for speaking with people (instead of treating them as another thing to handle with specials).

Later Ultimas would even allow for interactive conversations with characters. This was usually handled using keywords, where speaking with people would reveal some things that could be asked about, either with that character or others.

Ultima IV (Screenshot courtesy http://braid-game.com/)

Another difference between the two is that story is of much more import in Ultima, and ties more deeply into the play mechanics. One result of the difference in focus is that the original Wizardry holds up much better today than the first two Ultimas, whose story was rather slight, and even a bit goofy. Later Ultimas, however, have a world with nearly unequaled depth and complexity. The third installment has a whole hidden continent to explore, Ultima IV brings NPC relations to the true heart of the game in its virtue system and bossless design, and Ultima VII may have the most engaging RPG world ever devised.

Sadly, the last Ultima game was released over a decade ago now, and between Richard Gariott's exile from the company and Electronic Arts' decided lack of interest in their older properties, this state of affairs might never change. Ultima Online continues to cling to life, but the days of it being the MMORPG leader are long over. When it finally goes dark, it'll be the end of the greatest series of CRPGs ever known.

Further reading: Blogging Ultima

Designed by: Brian Fargo, Ken St. Andre, Alan Pavlish and Michael A. Stackpole

Influenced by: Post-apocalyptic pen-and-paper RPGs, with a bit of D&D wilderness exploration.

Series: Wasteland's sequel wasn't produced by the original developers and is widely regarded as inferior. The Fallout games, three of them as of this publication, are similar in many ways.

Legacy: The Fallout series. The Elder Scrolls series also seems to borrow from its wide-open design. Its implementation of multiple ways to solve some problems, is influential... but nowhere near as influential as it should have been.

In the early days of computer RPGs, there were a good number of games that were more wide-open in design than we know today. The lack of computer power, in a perverse sort of way, helped the cause of these games; because people didn't expect their eight-bit machines to be capable of realistic graphics and greatly-detailed world maps, developers didn't have to spend the manpower to provide them. Those days ended when games started showing that they were capable of providing a bit more meat on their grid-based worlds, and Wasteland, still fondly remembered by many, was one of the games that showed what those machines were capable of.

Wasteland has a weird position of being a kind of companion game to The Bard's Tale (a highly popular Wizardry-like game also made by developer Interplay). It contains a couple of sly references to that earlier game, and the screen has the same half messages/character roster, quarter character portrait, quarter display/battle messages system. Fights play out similarly too, down to using Bard's Tale's enemy groups and distance elements of combat.

And yet, behind the scenes, it appears that Wasteland is rather more ambitious than BT in its combat system; monsters exist as an entity on the tile-based map, and combat begins when the party enters their view.

Although the action of the fight, after actions are determined, is played as a stream of battle reports, as the monsters and the party close in for battle the player can check their locations on the area map at any time.

It's even possible to split the party up into multiple entities, each moving independently of the others in almost a roguelike fashion, and characters can even be in combat simultaneously in different areas, although as the developers note in the manual, playing the game this way is probably too annoying to be worth it.

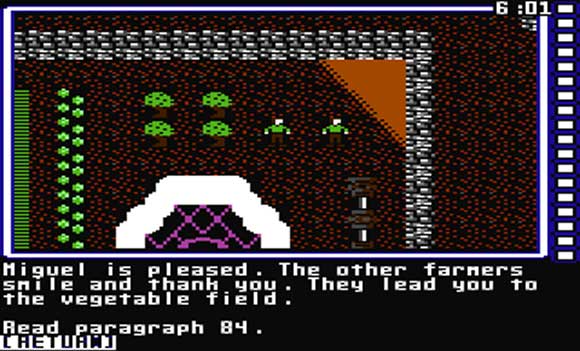

Wasteland (Screenshot courtesy http://nuttersmark.com/blog/)

One interesting thing about Wasteland is that, despite the harsh setting, the game is actually more forgiving than you might expect. Running out of health will often not spell doom for a character. This is particularly good because there is no way to revive a dead one. So long as a character remains no worse than Unconscious condition, he'll naturally regain hit points and wake up before too long.

Sometimes combat will reduce a character to Serious condition however, and that requires rather a bit more to overcome, including applications of another character's Medic skill. If not treated, Serious characters worsen over time and eventually die. There are also ailments characters can catch that can only be fixed by visiting a doctor.

The main reason Wasteland seems to be remembered today is the depth of its game world. It was one of the earliest games featuring quests to solve that offered multiple ways of carrying them out.

Some item-based goals had multiple copies of the needed object placed in the game world, allowing players to complete them from different places. The skill system aided in this; each of the player's four characters had skill ranks in a variety of skills, ranging from brawling to perception to lockpicking to more esoteric specialties.

Skills are quite expensive for a character to begin with. The first level in a skill costs one or two skill points, but each level beyond that doubles the cost of the previous one. Skills also increase with use, however.

There are too many skills for one character to know them all to any degree of quality, but by having them each specialize in some field, the player can cover most of the bases, and the holes in the party's skill set, once out in the world, help to distinguish each playthrough from each other -- and also, if one of the characters should happen to die, to make it easier to recover from the loss.

Designed by: Jim Ward, David Cook, Steve Winter, Mike Breault (Pool of Radiance), others

Influenced by: D&D, obviously. Also Wizardry, especially in its use of specials.

Series: SSI made many of these, at least seven. SSI also made a couple of Buck Rogers games using the Gold Box engine, and the original Neverwinter Nights (an early AOL offering) was essentially an MMORPG Gold Box game. There was even a publicly-released Gold Box AD&D construction kit in the form of the Unlimited Adventures tool.

Legacy: Probably every D&D-licensed RPG to come after owes a tremendous debt to the Gold Box line.

And so we return to Dungeons & Dragons for a moment. Let's first review the progress of the pen-and-paper game between OD&D and AD&D 2nd edition, which is the version that the Gold Box games utilize.

OD&D gave rise to two different, popular branches of the game, a version called just "Dungeons & Dragons" and was handed to TSR staffers to design, and "Advanced Dungeons & Dragons," which was Gary Gygax's baby, and substantively looked like a version of OD&D with all the supplements rolled in, as well as some additions.

OD&D contained a good number of "rule hacks," weird little special cases introduced for one reason or another. For example, in the original books, elves were the only race with special status, able to play as either Fighting Men or Magic-Users, but only one at a time, per adventure. A supplement turned this into D&D's strange "multi-class" rules, giving them the ability to do both, splitting experience between their classes.

It also opened up the ability to pick different classes, and allow other races to multi-class. But since the purpose was to allow races to seem special compared to ordinary people, humans didn't get access to these rules. But then humans began to look like a fool's choice for race, so they introduced the "dual class" rules.

The result was that the rules became ever more complex, and only really understandable to people who had played from the start. Then 2nd edition came out (after Gygax had been forced out of the company), and the rules became simple in some ways, but combat became even more complicated. These are the rules upon which the AD&D Gold Box games are based.

Up until that point, TSR had viewed the burgeoning field of computer RPGs with suspicion. They had released a couple of tools for 1st edition DMs (shamefully, still the best such official tools ever produced), but nothing much in the way of games. This changed with the introduction of Pool of Radiance.

AD&D was not designed to become a computer game, and thus there are some unusual interface challenges at work here. A big advantage coming from its trying to replicate a official pen-and-paper RPG is that some aspects of the game world which almost invariably get simplified out of a concession to workability on a computer did not with the Gold Box games.

Take, for example, Vancian magic, the (in)famous aspect of D&D versions 0-3 that had wizard and cleric characters memorize spells at the beginning of an adventuring day. At "the beginning of a day," even in table sessions of Dungeons & Dragons, is a simplification; 2nd Edition established complex rules determining how many hours of preparation magic users had to undergo before beginning to memorize spells, then the actual amounts of time needed to commit them to retain them. In play sessions DMs usually, and rightly, glossed over this needless complication.

In most computer RPGs, something as weird and flavorful as Vancian magic (something that is only really effective for people who have read Jack Vance's fantasy work) would be considered too much of an interface hassle to make up for the fairly-minimal atmospheric effect from using it. The Gold Box games do include Vancian magic, even though it required a great deal of interface programming at the time to accommodate it -- the games even accurately tally up the hours spent in memorizing spells. They also track encumbrance, and even the funky multiple coin types D&D used at the time, with at least one inn even refusing payment in anything but platinum.

The games themselves are remembered fondly by many players, probably because of their strong non-linear nature and challenging play. Like a semi-directed tabletop campaign, players are given many different possible tasks to accomplish and can do them in the order the wish, or switch between them. Many of the obstacles have multiple ways of overcoming them.

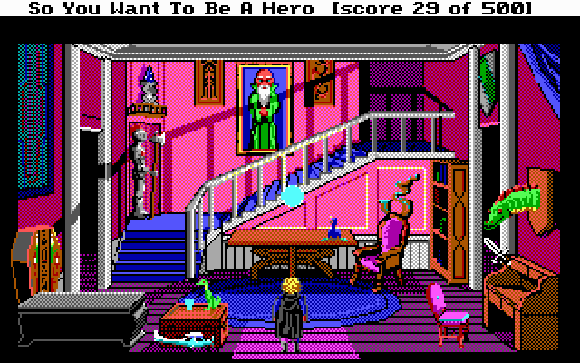

Pool of Radiance (Screenshot courtesy http://www.joystickdivision.com/)

For example, to enter the dragon's lair at the end of Pool of Radiance, the player's group can either fight its way directly in, or find the laundry and dress up in disguise to avoid some trouble, or rescue a prisoner to get a password to infiltrate the castle, or find a teleporter to take the party directly to the dragon. Pool of Radiance, in particular, was designed so much like an actual D&D adventure that TSR later released a module based upon it.

Second Edition D&D was still a fairly difficult game, and the Gold Box series didn't skimp on that difficulty, but they are leavened tremendously by the save game feature. Second Edition had the most complicated character generation of all the books, so abuse of the save game feature was pretty much required to make headway.

Technically players could switch out permanently dead or ruined characters with new ones, Wizardry-style, but the newcomers would join at the lowest level allowed by the scenario, but without the benefit of all the early experience opportunities his predecessor was able to claim.

I should say a few more words about ruining characters. D&D had resurrection spells, but they were risky. If the character failed his roll he'd be left dead permanently, and even if he survived he'd lose a point of Constitution, which meant lost maximum hit points for some characters.

Additionally, there was the Haste spell, which doubled a character's actions and movement for a short time, but at the cost of a year of permanent aging. Aging is one of those things that gets thrown around as a different kind of drawback in other games, but D&D aging is fairly difficult to overcome. And the Forgotten Realms and Dragonlance Gold Box games are arranged in a sequence, allowing for characters to move from scenario to scenario. Aging a few Haste-caused years per game, characters could easily be too old to function effectively by the end of one of the later games.

Pool of Radiance gets most of its exploration interface from Wizardry. Those games with an overworld present it as single screens of wilderness, with encounters sprinkled around. One of the things that 2E brought to D&D, and works fairly well for the computer games, is its "non-weapon proficiencies," which we might know better as, simply, "skills".

The crowning achievement of the Gold Box games was their fidelity to the 2E rules, which were generally unsuitable to computer play. They are not a direct port; there are plenty of spells, even the basic ones in the core rule books, that aren't present. (Some of them, like Reincarnation, would by mere implication have made the game much harder to develop.)

Many previous CRPGs unofficially used some version of the D&D rules as their base. (One of the telltale signs, visible in Wizardry and Bard's Tale, is the use of "armor class," and whether it counts down as it's improved.) AD&D 2E was the zenith of the game in terms of independence from computer simulations. It has been observed that a likely inspiration for 3E was its suitability to adaption as computer games, and that 4E seems downright MMORPG-like.

Further reading: GameFAQs hosts an excellent guide to the 2nd Edition AD&D rules.

Designed by: Corey Cole, Lori Ann Cole

Influenced by: D&D, graphic adventures (Sierra style).

Series: Five games. Even though considerable time elapsed between the later installments, it's still possible to take a character through all five adventures.

Legacy: RPGs seem to be coming back around to adventure game design, particularly in their use of object manipulation puzzles.

The time was that adventure games and role-playing games were considered close kin. Pen-and-paper Dungeons & Dragons adventures are held in what could be termed "narrative space," the players forming a mental image of the area using a description provided by the DM, stating what their characters were doing, which the DM folded back into his own internal representation.

Back and forth their descriptions go, defining the world's progress in an iterative fashion. Early adventure games were inspired by this kind of interaction, and even drew from some of D&D's other aspects; Zork had a fight with a troll the outcome of which was determined randomly.

But then the two genres split apart. Adventure games became about puzzles, especially object manipulation puzzles, but usually things that worked the same way each time. Meanwhile, RPGs went towards statistical simulation: things that were influenced by numbers and contained a strong random element. Further, the narrative gap between the two genres widened. In an adventure game, you played the part of some specific someone, someone like Arthur Dent, King Graham, or Roger Wilco, all of whom have a personality -- even if it's a fairly generic one. RPGs let the player create a character to take the role of protagonist.

But the key aspects of adventure games and RPGs are not incompatible; they just evolved along different tracks. In fact, most RPG characters end up doing many of the same kinds of things that adventure game characters do, just in a different interface.

They take things from place to place, they speak with other characters, they solve puzzles that often have to do with putting a specific object in a specific-object-shaped hole, they push magic buttons and pull switches. The real difference is that in RPGs this stuff is just a means to an end, something to break up dungeon exploration and combat sessions. (This also means adventure games tend to have rather better puzzles, since they aren't distracting from the "real" game.)

Considering the two genres' common roots, it's amazing that there aren't more crossovers between them. Probably the best known, most popular such crossover is the Quest for Glory series, a sequence of Sierra On-Line graphical adventures that handily combines the best of both worlds.

Quest for Glory (Screenshot courtesy http://hg101.classicgaming.gamespy.com/)

At the start of a game, the player chooses a class, Fighter, Thief or Wizard. The choice of a class determines which skills they get. There's an experience score, but it's mostly just points, without an effect on the game. Skills can be advanced by practicing them, however, causing them to creep slowly upward.

The most interesting thing about the game is that it is filled with skill checks that demands a player have one skill or another, but all the major puzzles can be solved with every class. There's multiple ways to solve most puzzles.

There's also a few things that can only be one with one character, but they aren't required to win. Ultimately this is the same idea that was used in Wasteland, indeed all skill-based RPGs, and it gives the game a surprising amount of replayability.

Best of all, like Wizardry, the games in the series allow the player to import a character from one game to the next. It's possible to take a hero from the beginning of the first game to the end of the last one, four games later, taking his skills and some equipment and money with him.

Very few games try to do anything like that today; it's a feature that seems to have mostly died off from gaming, although it still shows up in strange places; the Gamecube/Wii Fire Emblem games allow the player to import his party from one to another, which remains, to this day, the only use a non-Gamecube game has had for the memory card ports on the side of the Wii unit.

Designed by: Jon Van Caneghem (original designer, creator, producer)

Influenced by: Old-school D&D and Wizardry.

Series: Nine games, plus the spin-off "Heroes of Might & Magic" (itself a revision of New World Computing's King's Bounty) and some other side games.

Legacy: Difficult to say. Of all the classic RPGs, Might & Magic is the one entered most shamefully into obscurity.

Might & Magic is a series that's fallen into disuse lately, which is a great shame because, in many ways, it is the most faithful homage to the old-style, exploring-for-its-own-sake D&D campaign ever sold as a computer game.

First off, it is highly non-linear. Each game's dozens -- maybe even hundreds -- of quests and tasks tend to be scattered around the world in a semi-scrambled fashion. Players are left to their own devices as far as figuring out what to do and what level they should be at to do it.

I must remind the reader that this is a style of game that relies on the use of unlimited game reloading, so players can recover when they unpreparedly run into that group of Cuisinarts while less than level 200. Usually the player has no clue an area is out of depth for him until the monsters wipe him out.

Once granted this quirk, the M&M games are marvelously open-ended and wondrous experiences. They remain one of the few games to adequately express one of the most unique joys of the old-school RPG experience: that of unabashed powergaming. Might & Magic II has a magic space in one of its caverns that grants all the characters, one time only, a thousand free max HP.

Might & Magic

The series does have a story but it tends to be fairly... I suppose the word I'm looking for is "crazy". For example, in the World of Xeen games, the players are quested by the Dragon Pharaoh to save the world from the two evils of Lord Xeen and Alamar.

Along the way they beat up elemental lords, fall out of cloud worlds (probably multiple times), befriend a bunch of palindrome-talking monks, collect Mega Credits with which to pay for building a castle, stop a witch who likes turning kids into goblins, and many other things; these are just the top of my head. Most of these things can be done in any order, and there are literally dozens of other things to do in the game.

In Might & Magic II the players meet Lord Peabody (after rescuing "his boy, Sherman"), travel in time to prevent a fight against an undefeatable Mega Dragon, sack innocent orc villages, and at the end must solve a cryptogram within in a time limit.

These kinds of things could have felt like a massive series of fetch quests, but Might & Magic is too varied for this to become too noticeable by the player. The game allows players to spend time wandering around and getting into trouble however he wants.

It's not uncommon to have accomplished a half dozen quests before the player even knows someone in the game wants them done, and so ends up getting rewarded the moment the quest is officially granted. I'll tell you right now that I don't consider this to be a bad thing at all.

One of the most interesting design choices made by designer Jon Van Caneghem is the use of two types of currency, the usual gold pieces, and gems. Awards of both areas tend to rise as the player explores harder and harder areas, but they also both tend to ultimately be limited in number.

They're not always hard-limited, but there comes a time towards the end of many (if not all) of these games where all of the areas have been explored and there's no more to be found, even if there are ways to continue to earn experience points. The thing is that gaining a level requires both experience and gold, and while experience is the limiting factor in the early stages of the game, it is the player's gold reserves that more often limits towards the end.

Gems are an even more useful type of wealth that is used up in casting the more powerful spells. All of the revival spells, particularly, cost gems, as do spells that can permanently enchant items and perform other tasks that would break other games.

Tying this magic to a second type of wealth, and allowing scarcity to limit the supply of that wealth, helps Might & Magic's spell system to avoid some of the limitations that magic in other games suffers from.

They're supposed to be wizards after all; what's the use in having a wizard if you don't get to bend the rules sometimes? Might & Magic's chief innovation is in allowing just this sort of thing to happen, while keeping it within the balance of a larger game.

Designed by: Jay Fenlason, Andries Brouwer (original Hack), Mike Stephenson, Nethack "Dev Team" (Nethack), many contributors

Influenced by: Rogue, Hack, D&D.

Series: Just the one, although I suppose one could count variants as being of the same "series." In that event: Nethack TNG, Nethack --, Nethack +, Lethe Patch, Wizard Patch, SLASH, SLASH'EM, Sporkhack and others.

Legacy: Diablo and Diablo II were not directly influenced by Nethack, but they share Rogue as a common ancestor. A long-lived JRPG series, Mystery Dungeon, is informed by Nethack's design strengths.

For useful background information on the concept of a "roguelike", check Gamasutra's earlier article on the topic of Rogue.

Above, in the section on Wizardry, I remarked that the biggest thing that pen-and-paper RPGs had, and still have, over CRPGs is lack of flexibility. The player characters cannot do everything they could in a real situation because the computer cannot generalize the environment to the degree that this could be done, and doesn't have the creativity to improvise things in response to player actions.

The standard CRPG method of dealing with this is to provide the most important and obvious actions: Move, Attack, Search, Eat, Rest and stuff like that, and to specifically reduce the importance of other things. Nearly always this results in a game world that's lacking in scope for player action, since a truly ingenious player can often come up with something bizarre and useful to try.

The only RPG genre to make any headway against this long-standing limitation of the form is the roguelikes. Of all of them, they're the one to have overcome it the most. Indeed, the shining beacon that shows us that after all these years the problem may yet prove not to be completely insoluble is Nethack.

Nethack's solution, admittedly, may not be universally applicable. It solves the problem of players not being able to communicate what they want to the game by giving them an over-abundance of options, and it solves the problem of not offering players things to do with those options by using a lot of random content generation, hidden uses for abilities, and being content to let a few of those commands be usable only in occasional instances.

On that first problem, about communication with the game: Nethack has dozens of commands. Players can sit down, throw or wield anything they can carry, dip objects into potions, fountains or standing water, write on the floor, play musical instruments, disarm and reset traps, make offerings to the gods, and many other things. Not all of the commands are needed to play through the game, but Nethack's game universe is complex enough that the best players know them all, and know when they're useful.

On the second problem, that of what to do with the options allowed, it uses a lot of knock-on monster and item properties. Every item has a composition; things made of paper could be burnt by fire attacks, those made of metal rusted by water.

Monsters which are orcs automatically take extra damage from the sword Orcrist. Monsters with sight can be blinded by expensive cameras. These incidental properties provide a fair amount of Nethack's depth. Interestingly, they don't come as a result of an object-oriented design. Nethack is implemented in straight C, with nary a class statement to be found!

Nethack

Nethack

Nethack is a roguelike, and so I'm required to say something about one of those games' most controversial features: permadeath. (Okay, I admit it—I've been leading up to this.) Since Ultima and Wizardry, but unlike pen-and-paper games to this day, players are allowed, and even encouraged, to save games and return to them if things go badly, a design characteristic that makes it almost impossible for anything really bad to happen to the player's characters.

I make no secret the fact that I consider this one of the most pernicious aspects of CRPG gaming, that permanent disadvantages acquired during the course of play cannot be used by a designer because the player will simply load back to the time before the disadvantage occurred. Admittedly, the prevalence of this attitude comes from some older games that could easily be made unwinnable if the player wasn't careful.

However, it's reached the point where "adventuring" in an RPG rarely feels risky. Gaining experience is supposed to carry the risk of harm and failure. Without that risk, gaining power becomes a foregone conclusion.

It has reached the point where the mere act of spending time playing the game appears to give players the right to have their characters become more powerful. The obstacles that provide experience become simply an arbitrary wall to scale before more power is granted; this, in a nutshell, is the type of play that has brought us grind, where the journey is simple and boring and the destination is something to be raced to.

Nethack and many other roguelikes do feature experience gain, but it doesn't feel like grind. It doesn't because much of the time the player is gaining experience, he is in danger of sudden, catastrophic failure. When you're frequently a heartbeat away from death, it's difficult to become bored.

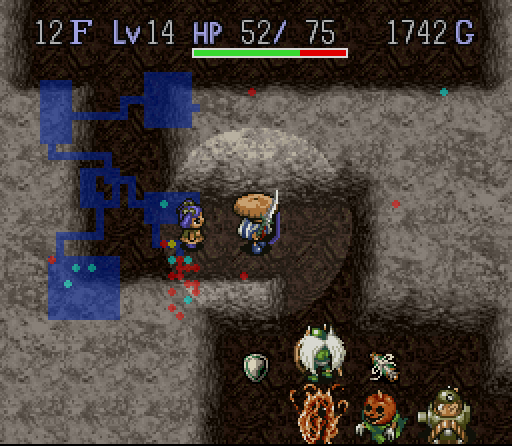

Designed by: Vijay Lakshman, Julian LeFay, Ted Peterson (Arena), Julian LeFay, Bruce Nesmith, Ted Peterson (Daggerfall), Todd Howard, Ken Rolston (Morrowind), Todd Howard, Ken Rolston (Oblivion)

Inspired by: Ultima Underworld, pen-and-paper RPGs

Series: Four main games, with a few expansions thrown in

Legacy: Fallout 3, also created by Bethesda Softworks, follows the open-ended style of the Elder Scrolls games, among other influences

The Elder Scrolls games take the non-linear approach to its height. Each is a full world to explore with many things to do which are not strictly necessarily to win. Morrowind, infamously, a multi-CD game, could be won in under eight minutes if the player knows what to do.

Of course, doing that, you don't get to see much along the way. And there is much to see! These games create huge expanses of territory to explore, huge caverns and dungeons, and have thousands of people to speak with along the way. Lead designer of Morrowind, Ken Rolston, an old hand in pen-and-paper RPGs design, has said this was to try to bring that kind of the free-form experience to the game.

How successful is this free-form experience? How wide-open is the game? Well, according to the game's Wikipedia page, the second Elder Scrolls game, Daggerfall, contains not one, not ten, not a hundred, but 15,000 towns. Italics, indeed! It takes several hours just to walk across the game's gigantic map.

How did something like this become possible? Wouldn't it take millions of man-hours to create all that space, and logic-defying compression techniques to squeeze it onto a CD? Well, no -- not if you create it all through fractal generation techniques, like the game world in space games Elite and Starflight. In other words: they used a pseudo-random generator, seeded with set values tied to each sector of game world, to algorithmically create terrain and contents.

The drawback of that approach, however, is that it's really hard to make interesting random content. Roguelikes are generally best at it (although those space games mentioned are no slouches). As a result, most people only say dull placeholder text, dungeons tend to be fairly lackluster and lacking in design, and because of some bugs in the generator there are a good number of bugs that make playing the game difficult, if not impossible.

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion

The Elder Scrolls IV: Oblivion

Later Elder Scrolls games went to using handmade terrain, and as a result have much smaller (but still huge) game worlds. And yet, the problem with creating thousands of game characters remains; many of the basic man-on-the-street inhabitants of the games' towns could nearly be clones of each other.

One advantage of the huge-world approach of game design is that there is room for a great number of sub-quests. Players can run assassination missions for important people, join and rise up the ranks in the guilds or military, join clans and houses, steal from merchants, create spells and potions, and permanently enchant items.

It's not quite as bizarre as Might & Magic, I notice, but there does seem to be considerable non-placeholder content there. The depth of the subquests is surprisingly deep considering that many people never see much of the content developed for the game. Daggerfall, Morrowind, and Oblivion all allow players to become vampires as a side-quest.

The initial state can be acquired as a status ailment in a fight, and then either cured or encouraged. While a vampire, players can drink the blood of sleeping characters and participate in vampire scripted quests, provided they stay indoors during the daylight hours.

Designed by: Ray Muzyka (director)

Inspired by: D&D, Gold Box and possibly Black Box games, perhaps Wasteland

Series: Two main games and two expansions. A few spiritual sequels using the same engine, the Icewind Dale series and Planescape: Torment, were produced by a different company.

Legacy: Neverwinter Nights and its sequel, but really, the continued relevance of the Dungeons & Dragons brand to computer gaming is largely due to Baldur's Gate.

Baldur's Gate was the game that rescued computer D&D from the wastebasket. SSI's bug-ridden Black Box games had nearly destroyed the venerable property's reputation. It was rescued by one of the coolest computer games ever to bear the brand. The game is still clear enough in the memory that it seems like it must have used 3rd Edition rules, but it turns out that it doesn't: all the mainline Baldur's Gate games used 2E rules.

Unlike the Gold Box games, Baldur's Gate doesn't use a first-person perspective, and it doesn't force the characters to stick together in one unit either. This is one of the more inventive breakthoughs of the game, in fact, and it seems like it may have been inspired by Wasteland's party-splitting feature. At any time, the player can switch to combat time, giving characters actions as if they were in a fight.

Baldur's Gate (Screenshot courtesy http://nostalgeek.wordpress.com/)

During fights the game can either be played in real-time or, since the pause feature allows commands to be queued to characters, as a kind of turn-based game. The game can even be switched to multiplayer mode, allowing a different human player to take the role of each character.

Although there are many NPCs in the game who can join the main character, in multiplayer mode individual characters can be rolled for each of the six party characters, instead of just the leader, a feature that was expanded upon in the later BioWare game Neverwinter Nights.

Another particularly awesome thing about it (and the later Neverwinter Nights) is that most of the NPCs in the game, in addition to having scripted dialogue and often quests and rewards to impart, are also attackable characters with stats should the need to use them in combat arises.

This helps the game to remain more open-ended and available to multiple solutions to problems than linearly-scripted. Baldur's Gate is possibly the game to best marry the old-school simulation approach of the early CRPGs with the later tendency to provide unalterable, hard-coded stories.

Finally, I don't think I can let this game pass by without noting the extremely well-done characterization of the potential party characters. I am not aware of anyone who has played this game who had a certain ranger named Minsc join his party who wasn't utterly enthralled by the character.

It is rare that a CRPG can produce a character with the kind of life and wit that you can imagine a tabletop player investing in his charge. He even has a Wikipedia page, which confirms that he had his origin in social pen-and-paper sessions. Go for the eyes, Boo!

Designed by: Rob Pardo, Jeff Kaplan, Tom Chilton

Inspired by: Earlier MMORPGs, Diablo

Series: One game with two expansions

Legacy: Oh, the games that have tried to copy World of Warcraft and have failed.

And so we have finally arrived at this: the 10-million-plus subscriber mumak in the room, the game that made mainstream in a way not seen since the days of D&D, the game a legion of other MMORPGs so desperately wants to be. What is the attraction here? Why is it that this game broken through the pop cultural barrier and gotten a South Park machinima episode?

It is not an easy question to answer, actually. If it were, Age of Conan would be doing better in its fight for survival. But there are some things that Blizzard is doing well that are easy enough to point out.

First, the game is unusually accessible to uninitiated players. In the tradeoff between ease-of-play and depth, it seems that Blizzard made a conscious decision to go with the former. The previous occupant of the throne of MMORPG King, EverQuest, took slow character growth to an extreme unmatched even by classic D&D. A player could spend weeks between levels later in his adventuring career, and getting killed even once was a huge setback in progress towards the next.

Most other MMORPGs games didn't slow character growth to that extent, but neither made it as quick as World of Warcraft, in which an avid player can gain a level in a single evening. If the game's systems weren't simple enough for an average player to understand then the game couldn't be as popular as it is now.

Second, the game allows for a lot of flexibility in character design. This fits in with the accessibility in that, once a character reaches maximum level, he can start over with a different character and have nearly an entirely different experience.

Part of this, perhaps, comes from the company's experience in developing the Diablo games, which bear a certain superficial similarity with World of Warcraft's equipment game. (Perhaps it should be said that the stock MMORPG equipment game is heavily influenced by Diablo.)

World of Warcraft

World of Warcraft

But do these things really explain World of Warcraft's popularity? By now, WoW's continued ascendancy seems largely assured just by virtue of its huge subscriber base; social pressures make MMORPGs more addictive when there are more people playing them.

WoW grew rapidly from the start due to Blizzard's massive reputation from its Warcraft, StarCraft and Diablo games, and made no obvious mistakes to drive people off. Just over a year later, the game already had five million subscribers, has over 10 million today, and in the absence of Star Wars Galaxy-style player disgruntlement catastrophes, looks to remain on top for the near future.

And yet, for its accessibility, there is a surprising amount of depth here for player-vs-player combat areas. Normal areas don't typically require players to obsessively tweak their armor or skills, but intraplayer combat areas tend to force players to optimize their characters to the height of their ability.

This is one of the hidden reasons some players hate PvP: it basically requires players to pay a lot more attention to their builds, since the standard a player must meet to succeed isn't an arbitrary monster yardstick set by a developer but the most effective builds that other players can devise.

As the user base discovers better and better builds, the players who really care about PvP optimize their characters according to that knowledge, forcing participants of that subgame towards being less casual, more serious players.

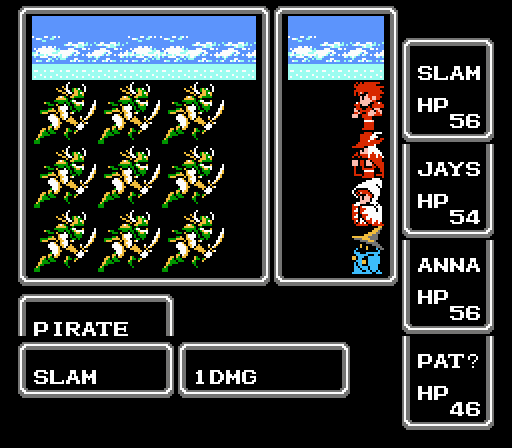

Designed by: Yuji Horii (scenario, creator)

Influenced by: Wizardry, probably also Ultima

Series: Eight to date, with a ninth on the way, and plans afoot for a tenth. There have also been numerous side series: Dragon Quest Monsters, Rocket Slime, Dragon Quest Swords... and Mystery Dungeon was originally a spinoff.

Legacy: Practically all JRPGs (the ones that didn't ape Wizardry, anyway.)

The story goes that series creator Yuji Horii was directly inspired by a copy of Wizardry seen at a Mac show. When he got back to Japan, he began work on one of the longest-running JRPG series of all, if not THE longest-running.

While other long-lived series have strived to keep up with the times and update their look and play mechanics, Dragon Quest has remained stubbornly a relic. The fighting mechanics are still similar to those from the original 1986 game. While the overall theme of the games has changed, the mechanics underpinning them remain the same.

And it seems to work. Dragon Quest has remained stubbornly old-school long enough that the nostalgic urge that has brought some of the older JRPGs back into prominence has arrived to find that DQ is still kicking it.

It doesn't get released nearly as often as it used to, but the same guy still writes the scenario, the same guy's in change of the music, and the same guy, Dragon Ball creator Akira Toriyama himself -- who probably has so much money now that he could buy Tantegel -- still draws the character art.

Hey, at least it's job security. The fact that the games remain the most popular series in Japan suggests that the basic mechanics of the series may be timeless.

Dragon Warrior III

Dragon Warrior III

The result is that the combat, which remains simple, takes up a lesser portion of the game's experience than the stuff around it, allowing it to slip, a little, into the background. Until Dragon Quest VIII, the game wasn't even 3D. DQ8 did a lot to revive the series' moribund fortunes.

Instead of driving further towards photo-realism as did the Final Fantasy games, it aimed instead to replicate Toriyama's character art as much as possible, with startling results. The series' lo-fi presentation has enabled it to target the Nintendo DS for installment IX, and plans are underway to produce DQX for the Wii, a decision that surprised some observers.

As for the games themselves, their use of some of the generally-abandoned features of older games means they have managed to retain some of the strategic depth that attended the classic computer RPGs.

Dragon Quest games still use, for instance, cursed items, gauntlet dungeons that players must conserve resources to pass, difficult boss monsters, and a generally upbeat atmosphere. The fact that the game can be slowly and steadily conquered by all players, equipped only with perseverance, seems to be key to the series' popularity in Japan.

Designed by: Yoshio Kiya (producer)

Influenced by: Early CRPGs.

Series: Eight games. To this day, only three games in this series to have made it to the U.S. One is the NES' Legacy of the Wizard, in Japan known as Dragon Slayer IV: DraSle Family. The other, Sorcerian, got a limited PC release by Sierra On-Line. Dragon Slayer: The Legend of Heroes hit the TurboGrafx CD. The NES sleeper action-RPG Faxanadu is a side-game to this series.

Legacy: It's actually hard to point to conclusive evidence of the games Falcom inspired, but the tendency to rework the entire game system for each installment was probably an influence on Final Fantasy.

I'm going to cover these game by game, because they're different enough from each other that describing one doesn't begin to explain the others:

Dragon Slayer:

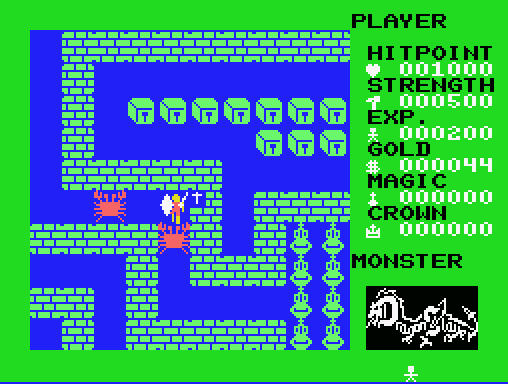

In a huge, deviously-constructed, tile-based world, a hero fights monsters and harvests items (by carrying them, laboriously, one at a time to his house) to increase his power so that he can fight more monsters. After hours of this, he becomes powerful enough to kill the biggest monster, the Dragon, and so proceed to the next level. (Level?!)

The hero can move his house around by pushing it, making the trip to carrying things home less time-consuming. Visiting home replenishes hit points, carrying a sword makes the player able to kill monsters, carrying home a power stone raises his strength, and so on.

The hero also has spells for some utility purposes, such as tearing down walls. Overall he is extremely fragile, so he must plan carefully in order to succeed.

Dragon Slayer (Screenshot courtesy http://hg101.classicgaming.gamespy.com/)

Dragon Slayer prominently displays a number of stats (using eight-digit numbers with lots of leading zeros) and pits players against lots of strange monsters, but it's more of an action game, really, than an RPG. Still, its loot-based character advancement system is in line with the older D&D way of doing things.

Xanadu:

Dragon Slayer is an overhead game. Its sequel, Xanadu, is more of a side-view platformer, although, when contact is made with a monster, the game switches to another screen for the battle sequence.

Battle is real-time and consists of the usual Falcom combat scheme, also used in the better-known Ys games, of ramming into enemies and hoping your health holds out longer than theirs. Despite the similar combat, Xanadu doesn't have a whole lot to do with Dragon Slayer, an aspect that became typical of the series.

Romancia:

Number three in line. Not a long game, and not a complicted game, but an incredibly difficult game all the same. The game is an RPG platformer, and this time doesn't switch to a separate battle screen for combat.

It's got quite a lot of obscure tricks that must be performed to proceed, sort of like Namco's Tower of Druaga. It also has a strict 30 minute time limit! There is a fan-made English translation of this game, which also fixes some minor bugs and restores some features found disabled in the code.

Drasle Family, a.k.a. Legacy of the Wizard:

One of only three Dragon Slayer games to make it to the U.S. It's infamous there for its immense difficulty, and excellent music. I've played all the way through this, and can say that it's incredibly large, extremely hard, and yet strangely fun to play.

The game makes you work for every little thing, but it's very satisfying when it's all pulled off A Let's Play video report on the NES version of the game is up on YouTube, and demonstrates well the game's many insidious traps.

Sorcerian:

It's a side-scrolling action RPG with a four-member party and Wizardry-like character creation! Your party members follow behind sort of like the options from Gradius. It's especially interesting because, also like Wizardry, there were further adventures that could be purchased to take your characters into. The game got a DOS release in the U.S. under the auspices of Sierra On-Line, although none of the add-on disks made it over.

Dragon Slayer: The Legend of Heroes:

A standard JRPG, nominally in the Dragon Quest mold, with the usual town/dungeon gameplay split, turn-based battles, and strong story elements indicative of the genre. As Xanadu earlier spun off into its own series, so did Legend of Heroes series; games in this series continue to this day in Japan.

Falcom's greatest hit was Ys, which is a shame as, for its good points, Ys is still painfully straight-forward. The Dragon Slayer games, for their weird action elements and platforming, paradoxically kept in closer contact with the spirit of old-school roleplaying. What a strange and wonderful collection of games.

Sources:

- HG101

- YouTube demonstration of Romancia

- Translation patch for Romancia (Geocities link)

Designed by: Shouzou Kaga (original), Keisuke Terasaki (director), probably others

Influenced by: Strategy wargames

Series: There have been many Fire Emblem games, and most of them never made it to the U.S., although this is changing; the original game finally made it to America recently as a DS title.

Legacy: The Shining Force line of tactical wargames is obviously directly inspired by this. A more indirect inspiration was probably Tactics Ogre, which went on to directly affect Final Fantasy Tactics and, later, the Nippon Ichi (Disgaea) tactical JRPGs.

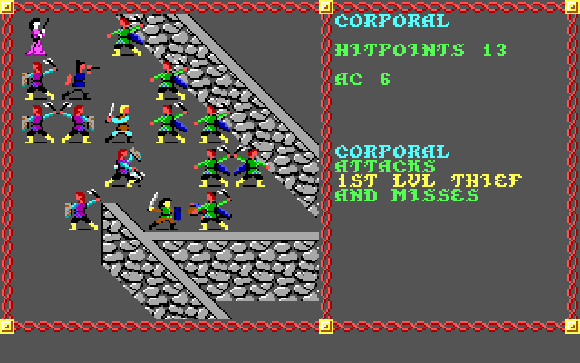

Fire Emblem is the first tactical JRPG wargame released, an inspiration for what would become an entire subgenre. It's a tile-based man-level wargame set on a grid with role-playing elements. Unique among computer games of the time, characters weren't interchangeable pawns but each of them unique, both in class and in stats. The more a character is used in battle the more experience he earns, making him subtly better in many areas.

Fire Emblem is a game of slow character growth. It's not hard for a unit to gain a level, but the primary advantage from this is each of his stats might increase by one. Every unit has its own level advancement percentage chance for each of its stats, information which is kept secret from the player, but even a character with great growth chances might just fail to gain a point in any one, or even any, of its stats, leaving him underpowered.

The Fire Emblem series are notoriously difficult games, so a bit of bad luck like this could make following battles rather harder. It's not unknown to reach the final battles of the game and reach opponents with defense stats so high that only one or two characters are capable of inflicting more than a few points of damage.

Fire Emblem (Screenshot courtesy http://hg101.classicgaming.gamespy.com/)

This is a bad situation for the player to be in, because if an enemy isn't killed in one hit, if it's in range it gets a free counterattack, and these same high-defense characters tend also to have high attack power. In Fire Emblem games, a character who runs out of hit points is usually dead forever. If this happens with a very useful character, the loss could be enough to make the game unwinnable in the end.

If you compare Fire Emblem to the third or fourth edition of D&D, the ones that emphasize tactical movement, they don't really look all that different from each other -- right down to the "support" for permanent character death.

Fortunately for players, the game does allow free restoring to the state at the beginning of a battle, so a favorite character can be saved... provided the player is willing to abandon all progress yet made in that fight. The ending even subtly changes based on who remains alive at the end of the game.

In some ways, Fire Emblem is more realistic than D&D. Magic users are relatively rare; most characters would be classed, in a D&D campaign, as some kind of fighter. Most weapons are non-magical, and even those that are have a limited durability. And most opponents aren't monsters but human characters.

D&D got its start in the rules of Chainmail, a not-dissimilar tabletop game which focused on the efforts of whole armies. It was Gary Gygax's idea to reduce the scope and add in fantasy characters and an overall "adventure" overgame to wrap the fighting. In Fire Emblem, the merest hint of that elder pastime can still be seen.

Designed by: Hironobu Sakaguchi (the original and many sequels), others

Influenced by: Dragon Quest, Falcom RPGs and (superficially) D&D.

Series: Twelve main games and XIII and XIV on their way. There have been a huge number of side games as well; the best-known are probably Final Fantasy Tactics, Crisis Core, Final Fantasy X-2, Chocobo's Dungeon and, more prominent in recent years, the Crystal Chronicles sub-series.

Legacy: A huge swath of JRPG production has been directly influenced, if not trying to outright ape, one or more games of the Final Fantasy series.

Is there anything to say about this series of games that hasn't already been said? Ah well, I will give it a shot anyway. Ahem.

Final Fantasy! Single-handedly saved Square from obscurity! Injected new life into the JRPG genre!

Final Fantasy! Made the fortunes of the Sony PlayStation! At long last brought JRPGs to something approaching cultural relevance!

Final Fantasy! Aped by countless game companies, stagnant and wallowing in its own cinematic pretensions. Seems not to know how profoundly goofy it has become. And yet, FFXIII will almost undoubtedly outsell every other game released the month it hits shelves.

Final Fantasy (Screenshot courtesy http://socksmakepeoplesexy.net/)

Final Fantasy (Screenshot courtesy http://socksmakepeoplesexy.net/)

These things do not concern us here, but what does is its design, and the Final Fantasy games, since about IV on, have had excellent design. Like the Falcom RPGs that came before (although not to their extent), Final Fantasy games have always made it a point to redesign the core systems for each new game.

Usually, each game features some key feature that serves to distinguish it from the others. Sometimes, as with Active Time Battle and the Job System, the feature proves to be so engaging in its own right that it's returned to in later games, or even become nearly standard through the industry. The mechanics are well-planned, they make characters powerful without becoming too powerful -- unless the player works hard to gain well-hidden super abilities.

It's good that Final Fantasy has such strong straight design elements because frankly, as a medium for actual role-playing and realism, it's sorely lacking. Every game system Final Fantasy has introduced has been something purposely counter to the traditional values of role-playing games. Active Time Battle: it's cool and all, but menu selections in real-time? Job system: does it make sense that a high level fighter be able to instantly become a wizard, or a dancer or a chemist, on a whim?

Espers and Materia: what now? Did anyone fantasize about these things before they were built into Final Fantasy? Those are the more defensible elements; let's not even get into "Dressspheres" and "Sphere Grids" and whatever else they're putting spheres into today.

Probably the most damaging influence it has wrought upon the JRPG field is Final Fantasy's complete divorcing of play mechanics from reality. Some of those systems award the player's characters a resource called AP, or sometimes JP. (Usually Ability Points or Job Points.) Often the fights that award high AP are completely different from the fights that award experience points. What AP is supposed to represent has never been adequately explained.

Increasingly in JRPGs, awards and points are bestowed more for the role they play in the fill-in-the-blanks design template, where spending time in the game makes characters more powerful, rather than even pretending to be depicting processes that could happen, even in a fantasy world. The source of this tendency I trace to Final Fantasy.

Why is it, exactly, that racing Chocobos should grant the player access to a hideously overpowered mega spell? Why does spinning the wheels of a slot machine cause damage to a foe? How could a character change so utterly that he has completely different skills and abilities just by picking up a new "job?"

All RPGs traffic in abstractions. To some degree, an RPG can only be as successful as the extent to which he causes the player to ignore how arbitrary it all is. One of the signs of the aging of the JRPG genre is how its games have, recently, become less careful about how blatantly made-up their various systems are.

Final Fantasy games are where this tendency originated. Its item screens, character clothing, magic trinkets and board games have become synonyms for each other, anonymous resources that mean nothing beyond the story events that provide them and the various advantages they grant. They may all be balanced (more or less) regarding the place they hold in the game, but, why? And yet, due to Final Fantasy's massive popularity, the tendency to tack on a strangely-named "system" has spread out to the whole of JRPGs.

In terms of game design, I must reiterate, all these things are perfectly fine. In terms of RPG design, though, they seem out-of-place. These games have turned into a strange amalgam of things that Gary Gygax would not have recognized.

Take Paper Mario, for instance. I love the Paper Mario games; they are as well-written as any other game you could point to, but are they really RPGs? Does the person sitting at the controller "play the role" as Mario, any more than he does in a typical side-scroller? Paper Mario also has a charming battle system, but it barely pretends to simulate anything.

The opposite approach, at least in the context of JRPGs, is that of Dragon Quest, which has kept pretty much the same battle system since the '80s. It's been updated with better graphics, and animations, and the occasional add-on feature (and sometimes those fall prey to the same thing as Final Fantasy), but it's still recognizably the same mechanism by which the blue-suited warrior went forth and slew the Dragonlord.

It is true that Final Fantasy games have been so influential because of their great popularity, and that popularity didn't arise randomly. But that popularity has resulted in people uncritically copying the negative aspects of the series in additional to the positive ones. Just like how everyone's trying to be World of Warcraft now by duplicating what they notice about the surface aspects of that game, without considering the strong design foundation the game is built upon.

Am I being too literal-minded, here, in my treatment of "role-playing games?" I may well be. But I have discovered that attempting to put Gygax and Arneson, OD&D and the era of Lake Geneva into any sort of context with late-era JRPG weirdness is asking for disillusionment. The disconnect between them is unavoidable, and too seldom remarked upon. It is the reason why I, and many others, feel I must add that "J" to the initials RPG here, instead of sticking with the letter "C."

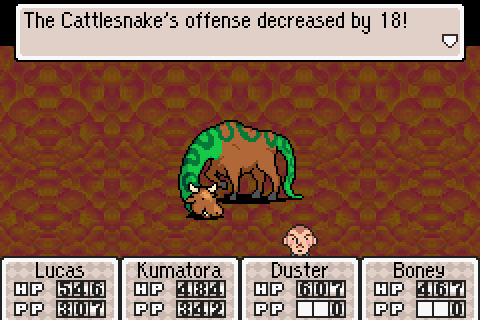

Designed by: Shigesato Itoi (director)

Influenced by: Dragon Quest, popular culture

Series: Three games, but they're incredibly fondly-remembered.

Legacy: Hard to say. As is sometimes the case with works of utter genius, they prove difficult to draw from. The early DS game Contact seems to draw inspiration from it in both art style and humor.

The game system of the Mother series is lifted, almost entirely, from Dragon Quest. Even in the days when the series began back on Nintendo's 8-bit Famicom, this was something of a throwback. While the story of the first game is good, it's not until the second game where the play of the game began to branch out.

Unique among JRPGs, and superior to most CRPGs, the Mother games are well-written and engaging far beyond the call of duty. Where many JRPGs are content to throw together a bunch of musical terms, a war between "light" and "darkness," elves and catgirls for party members and a whole lotta grinding for experience, the Mother games provide instead an astonishingly witty and erudite set of references, and yet the game doesn't throw them around haphazardly (as does, say, Xenogears).

Many articles on the series make it a point to mention that they are games that take place "in the present day" instead of in a fantasy or sci-fi setting. This quality isn't as unique as it used to be, but the game still succeeds because of its near total lack of JRPG "quirks."

What do I mean by that? Okay. The series doesn't have any of these things: anime character art, spiky-haired protagonists, emo drama binges or moony amnesiaics. Instead of trying to impress players with "dark fantasy" that reads like a teenager's poetry journal, the mood of the Mother games is generally light and silly.

Yet, it can turn on a dime to cosmic horror (end of Mother 2) or genuine anguish (an important event early in Mother 3, and its final scenes). Done falsely, the games could have turned out as tone-deaf as JRPGs often are, but instead the juxtaposition of the humor and the grief makes each somehow more effective.

Mother 3 (Screenshot courtesy http://mother3.fobby.net/)

To move to discussion of the game's play mechanics, one of the things that the game does fairly well is in its handling of status conditions. Most games are content to offer poisoning and leave it at that, but Mother 2 offers such bizarre ailments as mushroomizing (messes up controls & produces confusion in battle), possession by spirits (an invisible ghost opponent is added to fights who attacks random party members -- but can be harmed and even killed by enemy area attacks, curing the condition) and the dreaded diamondizing (sort of like a super-death; many means of character revival won't work on a character who's been diamondized).

One of the more gimmicky aspects of Mother 2 and 3's battle system is the "rolling HP counter." The party's HP totals are represented on-screen as numbers on an odometer-like readout. Losing hit points from attacks results in the wheels spinning and counting down to the new value.

However, a character doesn't feel the effect of running out of hit points until the number reaches its destination. So, a character who has "taken mortal damage," sending his dials on a trip to zero, can be saved by hitting him with a healing spell before the numbers get there.

The important element here is that the numbers count down in real time, regardless of message speed or paging frequency. It's a gimmick, but it does help to bring an aspect of panicky urgency to fights with strong opponents, which the Mother games have plenty of.

Mother 3 contains a new combat gimmick of its own, its much-discussed "sound battles." The previous games in the series would use different background music for different types of enemies. Mother 2 had rather a large number of these battle themes, and Mother 3 has even more, which is all the more impressive because the music affects battle.

Each background track has an unplayed "beat" track. If, after an attack, the player hits a button just in time with that beat, he does additional damage, and if he keeps it going he can do damage much in excess of the original hit.