Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Reflections and musings lamenting the death of the 'jump' button in adventure games and the impact this has on challenging game design.

In the office recently a discussion arose about ‘good old fashioned platformers’. You know the kind: Banjo-Kazooie, Spyro, Super Mario 64 – basically anything from the Nintendo 64’s hey day. Or made by Rare before they, well, you know… The general point of the discussion was why aren’t these kinds of games as popular as they once were? Whilst Ratchet & Clank are still going strong, many other beloved characters have either gone to pastures new – Spyro to Skylanders – or just gone altogether (whatever happened to Croc?).

To be honest I’m not here to discuss the rise and fall of the ‘N64-era platformer’. Whilst I’m sure that discussion is fascinating and has been tackled before, it led me to thinking and reflecting about something else: are gamers losing their ability to navigate game spaces or, more specifically, are gamers losing their ability to jump? And why?

Consider this scenario inspired by one of gaming’s favourite heroes – Lara Croft. Having scrambled up a ravine, negotiated around a mighty waterfall, shot an endangered species in the face, scaled a UNESCO-endorsed structure deemed sacred by the indigenous population and found some ancient Beretta ammo, Lara encounters her greatest challenge yet: a jump from one ledge to another. Carefully manipulating the camera we judge that a running jump will be required. Clutching the R1 button we cautiously position her on the edge, a couple of deft taps of the down D-pad button hops her back a square or two. We’re ready for take off. Holding down the up D-pad button, Lara hurtles forward like a bat out of hell. By god she can run, the edge comes closer and closer, a tap of the square button launches her into the air. We scramble for the X button. Lara reaches out her hands. The ledge comes closer … but not close enough. With the shrill death cry of a wounded hawk, Lara plummets to her death. Would you like to reload your previous save? If only you hadn’t pressed square so soon…

Chances are many a gamer has experienced this situation. The hope and excitement of the initial jump quickly followed by the crushing realisation of having to start again. The cycle of failure and progress is an inherent element of gaming and game design. Designers test the skills of the player; challenges create moments in which skills are refined and pushed to truly experience the game world. The ability to ‘read’ the game world has been a staple skill of games since Pong and Tetris. Understanding how the environment affects the player-character is key to progress – identifying when a running jump is required over a standing jump in Tomb Raider – whilst knowing which combinations of input to use and timing them correctly is the key to success.

But here’s the thing: I’m worried the ‘jump’ button – or more precisely, ‘failure’ - is becoming an endangered species in modern game design – especially in the high-stakes world of AAA game development.

Let’s consider the natural successor to the Tomb Raider crown, Uncharted. It features a jump button, true, but all the jumps are the same. All jumps are running jumps regardless of distance. Navigating the game’s [beautiful] 3D environments amounts to little more than aiming Nathan Drake in the clearly marked direction and pressing ‘X’. The environment is not actually a part of the gameplay. The ‘jumps’ are merely a means to add variety to what is essentially a linear path. No matter the terrain or the angle no thought is required from the player beyond press ‘X’ when in a large safe zone on the edge of a jump. The cinematic thrills of Drake’s acrobatics overrule the potential for gameplay thrills by blanketing the challenge to the player’s skill until they’re required for a gunfight (the true meat and bone of Uncharted’s challenge).

The Assassin’s Creed games take this design to the nth degree by making jumping and grabbing an automated action as soon as the player-character reaches an edge. On top of this, should the player-character (I’m going to choose Edward because he’s, you know, a pirate) leap from the top of a building directly to the ground not only does he barely take any damage at all but they instantly heal! As much as I adore the Assassin’s Creed games, I can’t help but feel they’re missing out on the potential to really challenge the player’s relationship with the incredible environments within. When jumping and grabbing is done for you there is zero fear of failure to keep the player focused. When understanding the layout of an environment in all dimensions is made irrelevant, grand 3D cities lose all meaning. By comparison, the Prince of Persia games (the spiritual predecessor to Assassin’s Creed) use the game’s environments and controls to great – and challenging – effect. When The Prince falls, he dies. When the player lets go of the grab button at the wrong time The Prince falls – and he dies. If the player wants The Prince to jump off of one wall to another they have to time their jumps accordingly. I fear it is this ability to use the skills/verbs available to the player in relation to a game’s environment that are being lost in favour of skills and verbs that only affect other characters e.g. ‘run’, ‘steal’ or ‘kill’.

Perhaps what I am truly lamenting is the separation of environmental puzzles from action-adventure games. The environments in Tomb Raider, Banjo-Kazooie and Prince of Persia were ripe with action and puzzles. Unlike a lot of modern games in which the only hindrance to progress is ‘kill this many enemies’, these older games used logical problem solving as a means to challenge progress on top of the enemies within them. Games such as Portal and QUBE show that environmental puzzle games – in which misreading the environment is the ultimate penalty - are still being made (and made well), but at the cost of any visceral challenge i.e. enemies.

Is it me, or are game environments becoming flatter? The inability to die or take damage from falling and invisible barriers keeping players safe effectively makes any sense of verticality moot. You might be on a ledge but that ledge has no relationship with the ground below it because you’re perfectly safe. One of the few new games I’ve played recently that still embrace the three dimensions of a 3D environment are the Dark Souls games. Keeping an eye on your enemies and the environment around you is essential for survival. It’s telling that a game with this kind of design is marketed as one of the hardest games around. Is it though? Yes, at first, but once you learn to consider each environment in three dimensions it becomes a much more manageable experience.

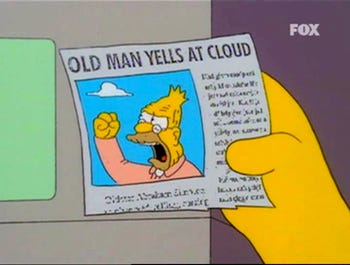

Experience. That might be the crux of the issue here. Once upon a time the nature of a game was to challenge the player, but as games have grown they have become experiences more in line with films and books. You can’t fail a film or book. You apply your attention and get instant gratification (assuming it’s well made of course). By softening the amount of input a player has over a game they are safe to simply absorb the experience before them; Drake freely climbs and jumps through ruins unhindered, Edward can’t fail as the hero. Current audiences don’t want the challenge of being these characters, just the experience. I don’t agree with the design ethos of punishing a player in order to teach them something; punishment is not learning. But neither do I agree with the current vogue of games which offer player’s nothing to learn beyond ‘press X to do X’ without truly appreciating the outcome of their actions. Going back to the original point about the lack of ‘good old fashioned platformers’, perhaps this is the reason why? In the current climate, as games diversify across wider and wider audiences, experience trumps challenge. Maybe somewhere there’s a happy medium to discover or maybe I’m just becoming a grumpy old gamer.

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like