Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Today at GDC Sony sponsored a talk on developing for PSVR, debuting an informal "VR consultation service" for devs and pitching them on PSVR's capacity to allow for local multiplayer VR games.

Today at GDC Sony sponsored a talk on developing for its upcoming PlayStation VR headset, and some of the takeaways may be of use for VR-curious game makers.

Speaker Chris Norden has been working with the technology for some time in his role as a senior dev support engineer at SCEA, and one of his first moves after taking the stage was to assuage developer concerns that PlayStation VR is intended to be a walled-off, proprietary platform separate from the rest of the burgeoning VR industry.

“We’re all friends; the VR industry is really small and really tight,” said Norden. “The VR industry needs to succeed, and everybody inside of it needs to succeed.”

As far as the hardware goes, Norden advises devs to develop to a headset with a 1920x1080 OLED panel with a 120hz refresh rate and the capacity to track either two PlayStation Move controllers or a PlayStation 4 gamepad.

He also recommends PSVR devs keep a defined “play space” in mind, which can seemingly encompass any area the PlayStation 4 camera peripheral can perceive.

“If you want to have a small area, if you want your players to be seated, to be standing, that’s okay,” said Norden. “Don’t feel like you’re constricted to just one thing," -- but also make sure to clearly communicate your players what sort of play area they need to play your game.

PSVR devs will also be capable of sending warnings to the player when they reach the edge of a defined play space, as the hardware wiill have system-level notification systems to warn a player when they get too close to edge of the play area (a system event sent to the game title.) The system will also be capable of flashing a big “Out of play area” warning when the camera can no longer see the player at all.

Norden also encouraged developers to consider players’ IPD (interpupillary distance) when designing their games, because it’s key to displaying an accurate, comfortable world.

“The PlayStation VR is designed to accommodate a wide range of IPDs,” said Norden. “There will be a way to set it, per user, in the system software.”

Each person’s PlayStation user ID will be tied to their personal info, including their IPD, so theoretically, says Norden, devs won't have to worry about setting it at all -- just developing to accommodate a wide range, as players can just log in to the PlayStation 4 using their PSN ID and the system will automatically adjust to match their IPD settings.

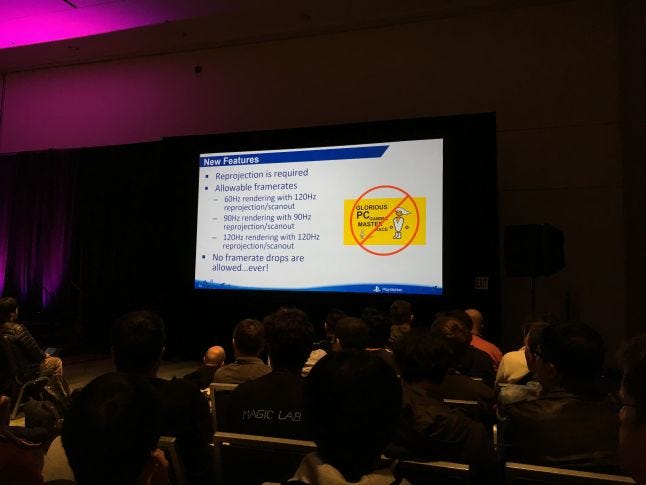

"You cannot drop below 60 frames per second, ever"

Norden seemed especially passionate about warning PSVR developers against letting their framerates drop below 60, even for a moment. Low or varying frame rates are bad news for VR game players, said Norden, and therefore it's bad news for PSVR.

“Frame rate is really important; you cannot drop below 60 frames per second, ever,” said Norden. "If you submit a game to us and it drops to 55, or 51...we’re probably going to reject it.”

“I know I’m going to get flak for this, but there’s no excuse for not hitting frame rate,” said Norden. "It’s really hard, and I’m not going to lie to and say it’s extremely easy...it’s really difficult,” said Norden. Still:

"60hz is the minimum acceptable framerate. Everybody drill that into your heads.”

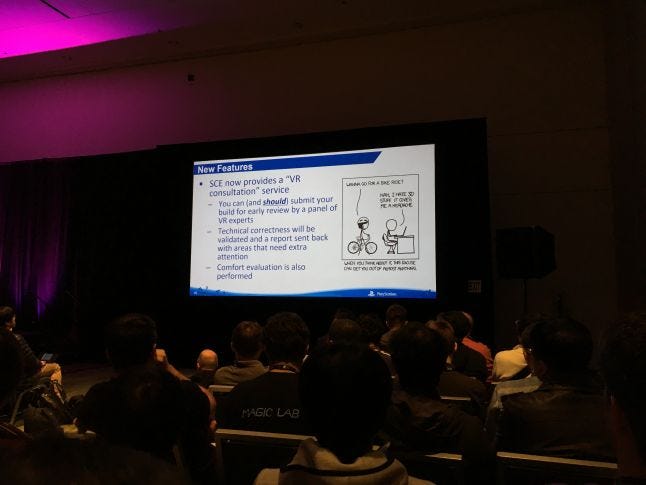

To stem the tide of bad VR design, Sony is launching a VR consultation service for devs

SCE is also moving to provide devs with a “VR consultation” service, which has the express purpose of minimizing how many nauseating, confusing or just plain bad VR games get pitched to PSVR.

The idea is to help VR devs sort out potential VR design hurdles early on, long before the games come in for cert. This “VR consultation” service isn’t mandatory, advises Norden, but it is strongly encouraged.

“We have a team of VR experts that will play the game...and look for technical correctness,” said Norden. “We’re not going to beta test your title or anything, but we’re going to provide you kind of a report of ‘oh, this is a possible nausea trigger. Oh, here you’re dropping frame rate.’”

Devs also shouldn't rely on using the PSVR's breakout box for any added juice, said Norden, because -- despite some reports to the contrary -- that's not at all what it's for.

“I see a lot of media misreporting what that little black box does, and it’s driving me crazy,” said Norden. He’s talking about the Processur Unit, the PSVR’s “little black” breakout box, and it’s not designed to offer extra GPU power, extra CPU power, or any kind of development expansion -- in fact, says Norden, devs are not meant to access the PU in any way.

What it does do, according to Norden, is object-based 3D audio processing, as well as displaying the social screens in PSVR (i.e. what outputs to the TV while someone is playing a PSVR game) and the PS4 system interface in PSVR’s “cinematic mode.”

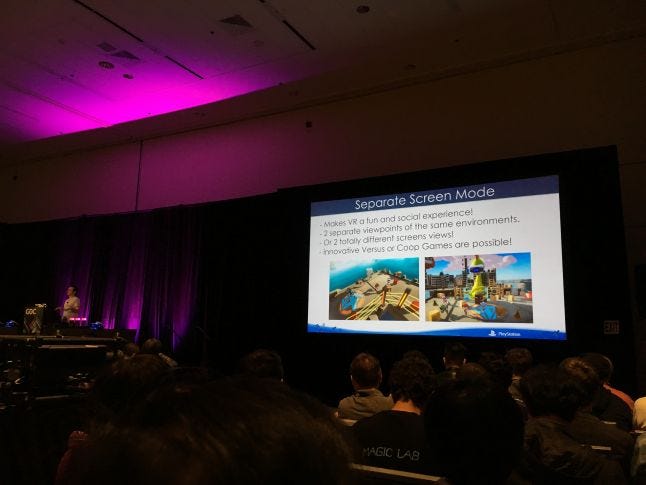

Norden confirmed that PSVR devs can either mirror the PSVR game to the TV or display something completely different (at 1280x720 30 hz) from what the PSVR wearer is seeing (potentially opening up room for designing asymmetric PSVR local multiplayer games.)

Sony is pitching "VR party games" as one of PSVR's potential strengths

Incidentally, the base PSVR (so, not counting regional bundles/deals) ships in October with one pack-in game/experience -- Playroom VR. SCE Japan’s Nicolas Doucet served as creative director on the game, which he describes as a “VR party game.”

“VR is often seen as a solitary experience,” said Doucet, briefly taking the stage to talk in depth about how Sony hopes devs will use PSVR’s separate screen display mode. “As we thought about it, PS4 users also have a TV in their living room and….surely the TV screen is something we should still use.”

Doucet pitched this to potential PSVR devs as a unique strength of the platform: the ability to create local multiplayer VR games, something Doucet has been experimenting with for some time.

The first prototypes were created in 2014, so they existed when PSVR was announced as Project Morpheus -- they just weren’t in a state where Sony felt comfortable showing them publicly.

As an example, Doucet showed a demo of a game where the PSVR wearer is a giant monster and four other players (who have PS4 controllers and are playing on the TV) are tiny robots trying to stop the beast from destroying a city.

This kind of demo is a good example of how the PSVR's 3D audio is meant to work: it’s object-based audio rendering (which Norden says are similar to Dolby Atmos or DTS X) that’s spatialized and is meant to work with headphones jacked into the PSVR’s cable. If you output sound to the player’s TV (as part of your local multiplayer PSVR game, for example), says Norden, don't expect it to be 3D in the same way.

Devs can also expect to have access to a “forced VR” mode that allows you to force all output to display to the headset as if ti were VR. You’ll also have a debug mode and a mode for displaying the “safe area” inside the headset where it’s most comfortable for players to look. That’s important to use, says Norden, because the pixel density of the headset lowers at the outer edges of the players’ view.

“In VR it’s important you don’t put things the player really needs to focus on outside the players’ vision,” said Norden. “If you’re going to glue something [like UI or a crosshair] to your face, even though we tell you not to, make sure it’s in that safe area.”

“Internally we’ve created a special sample which we’re calling the ‘comfort sample’,” says Norden. It’s now on PlayStation’s internal dev network, so “if you’re a PlayStation developer, go grab it,” because it’s an interactive demo that will help game makers quickly toggle back and forth between examples of good and bad PSVR content.

“I recommend you have everyone on your team try it,” said Norden. “Your artists, your designers, have everyone try it out.” The idea is to show VR developers what doesn’t work in VR, why it doesn’t work, and how they can fix it.

There was, of course, also a strong pitch near the close of the session (but before an awkward live demo) for developers to create games and experiences for PSVR (which launches in October for $400) because of the large established PlayStation 4 playerbase.

“We’ve sold over 36 million PS4s so far, since launch,” said Norden. “That means you have an audience of over 36 million people who can immediately pop into your VR game.”

Read more about:

event-gdcYou May Also Like