Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Read More from GDC 2024 | Keep up with the latest game industry event coverage from GDC 2024, including news, talks, interviews, and more from the Game Developer team.

"[Interactivity] is a way to increase player engagement in story moments, which in turn maximizes immersion."

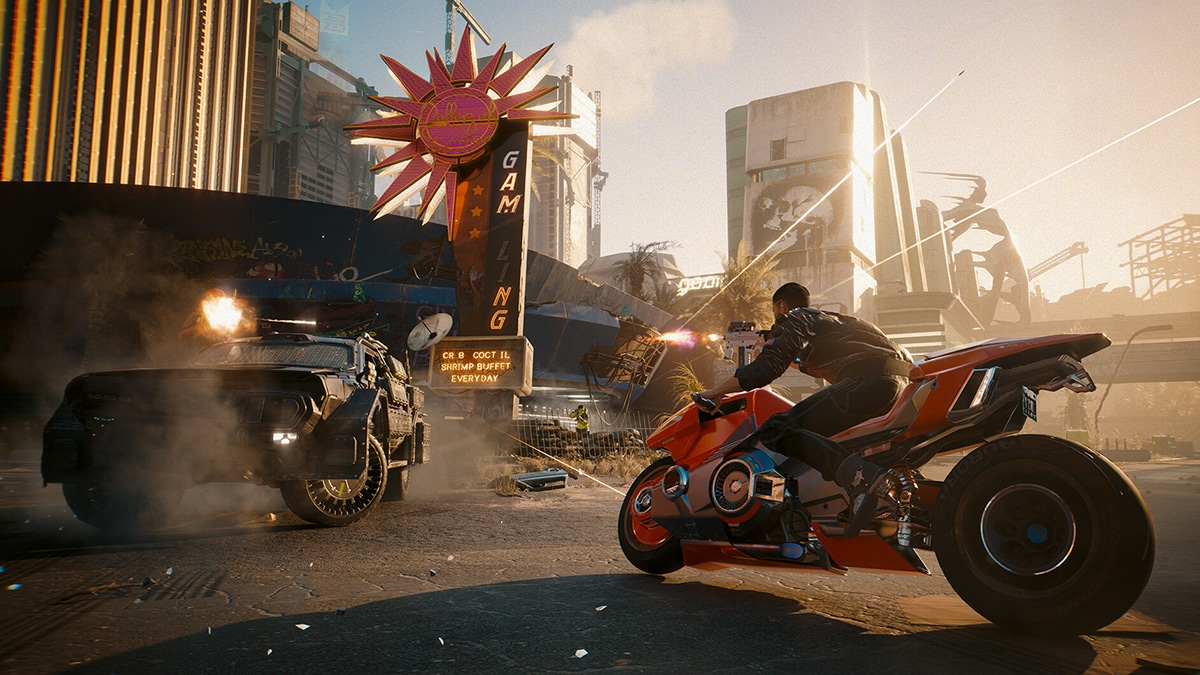

For Polish studio CD Projekt Red (CDPR), cinematics and interactivity are two sides of the same coin. The developer has made a name for itself building sprawling, multi-layered RPGs littered with choices, but believes it's the smallest decisions that can leave the biggest impact.

Discussing how the company adds layers of agency to cinematic scenes at GDC 2024, CDPR cinematic designer Kajetan Kasprowicz explains the trick is to create "hidden choices with small ripples."

For Kasprowicz, interactivity is defined as "the ability to control the flow of the cutscene not only with choices, but also with actions." That could mean allowing players to interact with elements of the world or engaging with (and perhaps even outright avoiding) certain dialogue options. He notes interactivity shouldn't be confused with reactivity, which is mostly concerned with acknowledging player choices.

Highlighting how that might manifest in-game, Kasprowicz, pulls up a clip that shows how, during one conversation in Cyberpunk 2077, players could either choose to respond to an NPC when beckoned or dismiss their summons and push deeper into the scene. There's no on-screen prompt that indicates this choice will have consequences, but there'll repercussions down the line depending on how players behaved.

"[Interactivity] is a way to increase player engagement in story moments, which in turn maximizes immersion, which helps [players] experience the story in the fullest way possible," he says, outlining why those moments are important. As for how CDPR defined "cinematics," Kasprowicz says they are basically "interactive story sequences."

"Whenever you talk to somebody in the game, it was a cinematic in our books," he adds. "They were structured similarly to a classic movie screenplay, so usually every encounter was written in such a way that it had some exposition in the beginning, a conflict, and the resolution at the end."

Even with those definitions to hand, combining both cinematics and interactivity became a double edged sword—largely because it was incredibly difficult to make the numerous confrontations players encounter pay off in a meaningful way. Kasprowicz says the sheer size of Cyberpunk 2077 meant implementing a myriad of substantial payoffs would have been "impossible," mainly because it would require the team to account for "tons of permutations" in the story. And yet, the studio noticed that in those moments where interactivity and cinematics did coalesce, players took notice.

"We course corrected for the expansion," says Kasprowicz, referring to how the studio adapted its philosophy for Phantom Liberty. "We felt that real interactivity was the next step, so we set our sights on exploring this aspect in the content we were making. Interactivity has a small caveat though. Similarly to action, it needs to be included in the screenplay to work well," he continues. "It's impossible to make it meaningful enough to warrant the extra cost after the script has already been written. But the payoff is worth it. Everything that players do themselves that is followed by a reaction has a much higher meaning to them."

As mentioned earlier, however, big interactivity is hard to achieve because you need those colossal payoffs. Yet, CDPR was reluctant to dismiss the idea entirely and began experimenting in shorter, more self-contained stories called 'Gigs.' Kasprowicz explains these stories could be created locally by individual teams and didn't need to slot into a greater whole. In the original Cyberpunk 2077, Gigs would be rather straightforward quests with clear objectives like steal a vehicle or wipe out mercenaries. In the expansion, the focus shifted towards creating "open gameplay experiences."

"They were stories that reflected the themes and tropes we touched on in the expansion but weren't necessarily connected directly to the main story," Kasprowicz adds. When it came to blending interactivity and cinematics in Gigs, he says CDPR wanted to create moments that were "indistinguishable from regular gameplay."

Offering an example, Kasprowicz rolls another clip that shows how players can resolve a hostage situation by choosing to pull out their gun and shoot the (potentially) hostile NPC at any given moment. Alternatively, they might choose to continue the conversation, waiting until the NPC places down their gun so they can snatch it away. Then, if combat is initiated, the encounter will be significantly easier. There are other resolutions, too. Players can let the NPC kill the hostage by refusing to intervene or even speed up the altercation themselves by offering encouragement.

The Gigs in Phantom Liberty are filled with interactive cinematics like this, many of which also push players to harness their specific character build in unique ways. Looking back, CDPR viewed the experiment as a resounding success. Kasprowicz says those smaller, more self-contained interactive cinematics effectively engaged players because they achieved a balance between interactivity and narrative flow. He claims it was absolutely worth investing in those scenes because they were hugely impactful in the eyes of players.. He even has the receipts to prove it, and says that a huge number of players dropped words like 'immersion' and 'story' in their positive user reviews.

Before bringing his talk to an end, Kasprowicz stresses that anybody eager to implement interactive cinematics, must effectively plan for them from the outset. If you attempt to retrofit them into your project, you'll only be setting yourself up for failure.

You May Also Like