Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

This priority system aims to help game designers reward players well and keep them playing. Cross checking your games with this can reveal strengths and weaknesses in your reward structures and provide guidelines for improvement.

Introduction

Rewards are an important feature of any game, and as such, can be found everywhere across all genres. Rewards can come in any shape or size, and when given to the player appropriately can greatly increase their enjoyment of a game, motivating them to continue to play.

Rewards can even have a player do something that they don’t want to do, or don’t enjoy doing (which is quite opposite of the purpose of playing a game). Many players will do annoying, tedious or boring things for rewards. The ability to have a player do what they dislike of their own volition attests to their power. They are an essential tool to a designer.

Designing Reward Structures

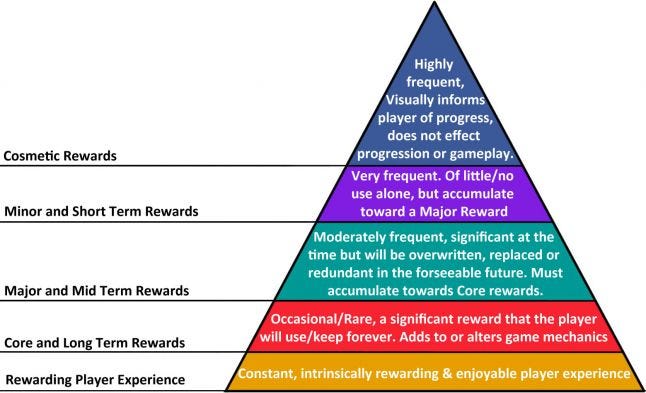

Rewards shouldn’t be included on a whim; they must be scheduled and structured. The following diagram is a hierarchy of needs, adapted for reward structures.

Fig 1: Hierarchy of Rewards in Games

Based on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, each section is a prerequisite to the one above, and can greatly enhance the one below. If a section is missing, however, those above it become ineffective. When designing a reward structure, it is important to work from the bottom of the hierarchy upwards to achieve a solid foundation. It is therefore important that each section is linked to the next. The higher up in the hierarchy, the more frequently the reward should be distributed; a fractal-like pattern should emerge (i.e. 10 minor rewards = 1 major reward, 10 major rewards = 1 core reward). It doesn't have to be strictly fractal of course, but minor rewards should considerably outnumber major rewards, and so on.

As we move upwards through the hierarchy, rewards become less intrinsic/more tangible. The bottom of the hierarchy is the most fundamental and intrinsic of rewards to the player – the player experience. At the other end of the scale, the top is purely cosmetic and cannot exist without the rewards listed below – however it works to enhance those below. Think of a scope for a rifle. The scope is great, and makes the gun much better; but it is completely worthless without the gun.

The following gives an overview of each section of the hierarchy and what kind of rewards may be found therein. Examples here will often be of the kind found in adventure or RPG games, but the principles can be applied to any genre. The rewards structure should always be designed in order of importance - from bottom to top.

Rewarding Player Experience:

Before considering anything else in detail, the player experience must be perfected. Good gameplay and immersion must first be obtained through the mechanics, aesthetics and UI (including essential player feedback). It is difficult to define whether this section is fulfilled, as fun is something that can only be experienced. The player must enjoy simply playing around with the game. The Grand Theft Auto franchise achieves this very well - who hasn’t switched it on, then ignored the missions and started wreaking havoc until they’re killed? There is no set goal to this, no rewards given (in fact the player is punished by losing ammo and paying hospital bills), but people do it because the gameplay/mechanics themselves are so much fun and intrinsically rewarding. Few games are fun to the extent that a person will play them with no prospect of rewards at all. Perhaps this is why GTA is so successful.

Core and Long Term Rewards:

Once the player experience is perfected, consider the core/long term rewards. These are very big rewards that the player will have forever. Examples include major plot developments, major milestones in opening new content (reaching a new island in Grand Theft Auto for example), or receiving a new game mechanic, such as those given after every boss fight in Crash Bandicoot 3. As these are the biggest tangible rewards that the player will receive and can affect the intrinsic experience, they should be given only occasionally. This retains their value and prevents annoying the player. People would become frustrated if they earned a new ability every 10 minutes; they'd never learn how to play.

Major and Mid Term Rewards:

These may be levelling up, completing quests, gaining large quantities of XP or money, etc. These rewards are significant to the player at the time but are not end rewards that are kept forever. They are very rewarding in themselves, but are also means to and end and will eventually be overwritten, replaced or become redundant.

Short Term and Minor Rewards:

These are small, frequent rewards which on their own do not benefit the player, but accumulate towards a bigger reward. Examples include collecting an item, small amounts of money/XP for defeating an enemy, or completing a stage in a mission. Just as Major rewards are means to a bigger end, Minor rewards are also means to an end on a smaller scale (the end being major/mid term rewards).

Cosmetic Rewards:

This is the final section to be considered. At the top of the hierarchy, they are purely cosmetic, serving only as a visual measure of the player’s progress. In some cases they are simply informative, such as numbers appearing on screen when you add to your score, or the squad selection screen in Mass Effect – the player can guess that they’re about halfway through when they’ve filled half of their squad slots.

On the other hand, visual progress elements such as unveiling a map or filling a bar can actively encourage players to do things that they would not do otherwise, as can achievements depending on design. A player might play for 10 minutes longer where they would have otherwise stopped because their XP bar shows them how close they are to levelling up. They may not attempt to round up and defeat 10 enemies with 1 grenade if there was not an achievement challenging them to do so, and may not just run around the entire area if they weren’t revealing their map.

While a game can still be enjoyable if the cosmetic rewards are removed, they will enhance the player experience as players like to see how they're doing. Visual rewards are vital in helping the player to gauge and anticipate rewards which is an encouraging motivator. Visual rewards never actually affect progress or any other aspect of the game at all.

There is a blurred line between the player feedback (mentioned at the bottom of the hierarchy), and cosmetic rewards (at the top). Player feedback is essential communication to the player, but cosmetic rewards can exist on their own (as with achievements, etc), or tie into player feedback for visual enrichment. One big difference between the two is that omitting essential player feedback can be game breaking, or at least break immersion. An example of essential feedback is seeing your avatar animate as you move around in the world. if it simply floated across the landscape this would completely break immersion and make it unplayable to many players. A problem like this is found to an extent in Oblivion and Fallout 3 (3rd person). The avatar animates but not it doesn't match its direction if running diagonally, so the character appears to float around. When playing in 3rd person this can completely break immersion. You can see an example of this here.

While it should be designed bottom up, the player will often experience much of this hierarchy from a top down perspective. They will experience cosmetic elements and minor rewards to begin, such as obtaining a task (this is where they are initially given the prospect of rewards), then minor rewards such as collecting items and XP, which lead to major rewards earned by completing the quest or levelling up, and eventually core rewards such as a new mechanic or unlocking a new world.

Application to a successful game:

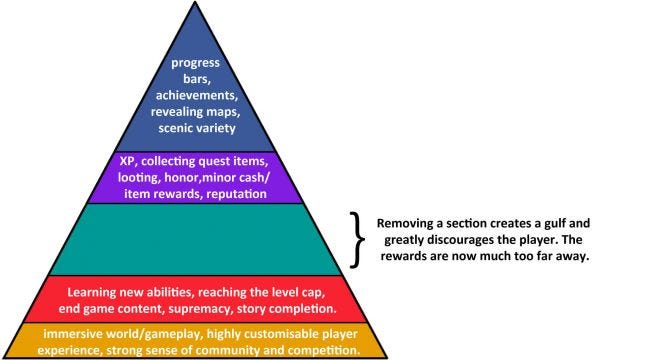

This hierarchy includes rewards featured in World of Warcraft, a very popular (and notoriously addictive) game.

Fig 2: A Basic reward structure of World of Warcraft

(does not include all rewards)

These are just a selection of the rewards offered, but it is clear that the game is abundant in rewards on every level. The world and the gameplay are immersive and such high customisation of the player experience (classes, specialisations, PVP/PvE, RP, and so on) means there are hundreds of player experience combinations in one game.

Add to this the limitless supply of rewards of all kinds which all tie in to one another and accumulate towards something. Then, to top it off it is peppered with random chance rewards. Even the most mundane creature can drop disproportionately powerful rewards on very rare occasions. There is always a reason to keep playing; this is clearly a very strong reward structure in every aspect.

Application to an unsuccessful game:

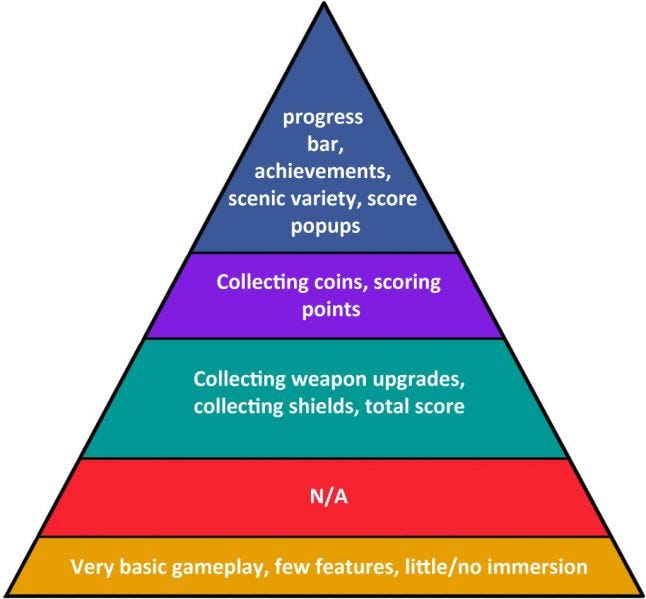

As part of an experiment for my dissertation I created a very simple 2D space shooter game. Though it was fit for the purpose of an experiment on rewards and yielded conclusive results, the game would not be popular or successful in the real world. After developing this hierarchy I decided to apply it to my game:

Fig 3: Reward structure of a basic 2D space shooter

The game is strong at the top and gets weaker as we get to the fundamentals of the hierarchy. There is no hope for this game on the market today no matter how good the upper sections are, because the lower sections are not fulfilled. As well as gameplay being lacklustre, an entire section is missing. Tight time and resource limitations meant that the game focused on tangible rewards which could be created quickly and easily. There was no time to invest in excellent gameplay; it just had to work.

It is easy to draw a comparison between this game and popular arcade games from the 70's. These were successful in their day, though they did include the long term reward of top slot on the leaderboards - but today their main appeal is arguably nostalgia. Todays games have far more sophisticated gameplay and reward structures, so a game like this cannot compete.

Consider the World of Warcraft hierarchy if a section is missing:

Fig 4: World of Warcraft’s reward structure with a section removed.

With this section missing, the hierarchy doesn’t make much sense. Level increments are gone, for example, so now the player must go from level 1 to level 90 (or whatever its new name would be) in one grind. The player would be consistently weak and the suddenly immensely powerful, but only after an inordinate amount of time. Needing 999,000,000,000 XP to reach the next/last level is far too discouraging when the player is getting 20XP per enemy, even more so when their XP bar never seems to budge. Bitesized chunks are essential.

The removal of this section has completely devalued those above. The minor and visual rewards contribute so little to the next goal that they don’t feel very rewarding at all. Players are much happier and more likely to play if they feel that their goal is realistically obtainable.

Summary

Quality does not equal quantity, but it is important to have at the very least one reward in each section. Aim to fulfil each section of this hierarchy to a high standard and ensure that they accumulate towards one another. Though it has not been around long enough to be tried and tested on a large scale, following this structure should achieve a strong, structured, rewarding player experience.

While many of the examples throughout this article are based on action adventure/RPG type games, they can be applied across any genre, from puzzle games to sports and racing. By applying this model when designing a reward structure, the designer can ensure that the game has solid foundations and is rewarding enough to make the player feel good. This can ultimately keep them playing the game.

Though I've tested theory this on multiple games and have developed it over time, I am always keen to improve. If you have any suggestions feel free to let me know (:

Thanks for reading!

Read more about:

BlogsYou May Also Like