Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Road to the IGF 2022: Cai Cai Balão gives players a glimpse into the dangerous world of Brazilian balloon artists. Once a proud tradition, this art style has been criminalized by the government, pushing these artists underground.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series.

Cai Cai Balão, which was nominated for Best Student Game at this year's IGF Awards, gives players a glimpse into the dangerous world of Brazilian balloon artists. Once a proud tradition, this art style has been criminalized by the government, pushing these artists underground and forcing them to take great risks to preserve their art and culture.

Game Developer spoke with Look Up Games, developers of Cai Cai Balão, to talk about the importance of capturing the dangers of this form of artistic expression, the members of the culture who all helped contribute to the game, and what they hope to accomplish by spreading awareness about the art and its persecution through a game.

What's your background in making games?

Sissel Morell Dargis, Cai Cai Balão game director: This is the first time I had an opportunity to direct a game.

How did you come up with the concept for Cai Cai Balão?

Dargis: They say that ballooning is like a disease—that once you’ve been infected, there is no going back.

Your life changes and evolves around the balloons. That’s pretty much what happened. I was 19 when I released my first balloon. The more I got dragged in, the more wild it became that nobody really knew about this. I guess it’s natural to want to share what you love, and for people to understand you—especially when it’s demonized in the way it is in Brazil. And as more and more friends got arrested, balloon workshops invaded, and penalties rose, we wanted to make something that could bring a different light to the culture.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Dargis: We used a very traditional setup with Unity as the game engine and Github Desktop as source control. Unity has, of course, a lot of build-in tools and options to create custom tools that we used. If we were to highlight any, it would be a custom event system we used for audio and game events, as well as an animation recording tool that was used to generate data of bone positions throughout an animation. The latter was what made Motion Matching possible. Since we used an agile development approach, we also used tools like Trello to keep track of tasks, and for our testing station we used Jenkins to deploy the multiple builds to a QA computer.

Cai Cai Balão draws from a vibrant history of Brazilian art. Can you tell us a bit about this culture and scene built around creating flying artistic displays using balloons? And about the criminalization of this art style?

Dargis: The balloon culture is more than 300 years old, brought to Brazil by the Portuguese—who traditionally used the balloons to celebrate Sao Joao, but it slowly became bigger and bigger as a culture for itself. Throughout the 80's, the balloon culture grew, both in sizes of balloons and number of "baloeiros" (members of the culture). The old timers of the culture, who experienced it before the criminalization in 1998, say how the sky would be so covered in balloons; it was like the Milky Way descended.

The main argument for it to be a crime is that they can create fires. However, there are many other theories to why this exact culture was hit so hard by the authorities. And a lot of speculations of why it was never reconsidered in a regulated, legal form. Some say that it’s because nobody saw it having any commercial benefit, and therefore nobody fought for it. So the culture continues in its marginalized and criminalized form, which in the eyes of the government means an uncontrollable “air terrorism” (as labeled in media).

However the balloon culture has many rules and codes within that are to be respected and followed. As in any other community or brotherhood.

Can you tell us how the modern scene in this art style inspired the gameplay of Cai Cai Balão?

Dargis: We wanted to convey the thrill of the balloon hunts, as a counter to navigating in a world that, at times, is hostile, and where the police persecutions happen every day. We wanted to show the balloons as the art pieces they are, even though the digital versions are just snippets of what these things actually are.

We also tried to emphasize another side of daily life in a favela—of keeping together and helping each other.

What interested you in capturing this scene with your game? In creating a gameplay experience about baloeiros?

Dargis: Because it is a crime, the balloon world is a very closed world that few can enter. Even though it’s huge. You get 500 dollars for snitching a baloeiro, so of course they have to remain secret and hidden.

However this is not what the majority of the baloeiros would want it to be. They were forced into hiding, which then also leaves a lot of power to the media who can say whatever they want, as no one counters that image. Our dream was to create an experience that would serve as a window into the balloon culture.

I believe games can sneak into different spheres of society, if we want to. Of course, there are limits to how much a small game like this can do, but I believe that all small steps are important. Just the fact that this game can make people discover or appreciate balloon culture is already a big victory.

What challenges came from capturing this experience of rushing after balloons while avoiding police, dogs, and snipers?

Dargis: I had been on a lot of balloon hunts myself, and even though it’s like a game in real life, real life, makes it thrilling in a different way. Because you can actually die or get beaten up by a cop.

With other baloeiros, we would come up with a bunch of things we wanted in the game and the designers and programmers would very patiently explain what was actually possible with the resources we had.

I think the biggest realization, was that what's intriguing in real life might be super boring in a game. And that was really hard to accept. Because I have a lot of respect for real life. Real life is wild and intense, adding up all kinds of juicy funky stuff to make it even more crazy, felt like a lack of respect to the actual suffering or consequences that real life has. However, it goes the same way for the sense of victory. In real life, the stakes can be felt on the skin. In a game, the stakes are forcefully raised so we can feel them, even when they’re not on our skin. So I guess I realized I can never fully convey real life as it is. But I can come close enough for people to taste it.

I think you have to be open to explore these fusions with real life and see them more as metaphors and perhaps accept that what you are creating just becomes another interpretation/expression of the culture.

You've stated that you involved actual baloeiro artists in the narrative and voice acting. Why was that important to you to do? What made you involve these artists directly in this story?

Dargis: This dream was not only mine, but that of my baloeiro friends. This includes Ton, whom the story of the brother—who is the older baloeiro—is actually based on. Many baloeiros always talked about how they had dreamed about a balloon game since childhood. So, there was no way it could be done without them, and that was always what made the project alive, you know? It’s made with friends; with real people who are all giving a little piece of themselves, either by voice, anecdote, or video.

It was super hard as well, of course. Because everybody had really high expectations of what it should include, and as I explained before, it’s really hard to translate real life into game mechanics (that can actually be done). Then Sergio, my sort of godfather in balloons, died three days before delivery. This was one of the harder things about dealing with real life. Polishing was done with tears.

Cai Cai Balão features a striking musical and visual style as well. What inspired the style of the game? What drew you to the musicians you used in the game?

Dargis: I think when you do things with no budget, you can basically only rely on the love from people that believe in either you or the project, so it’s like a natural selection process of who actually sets their mark on the product.

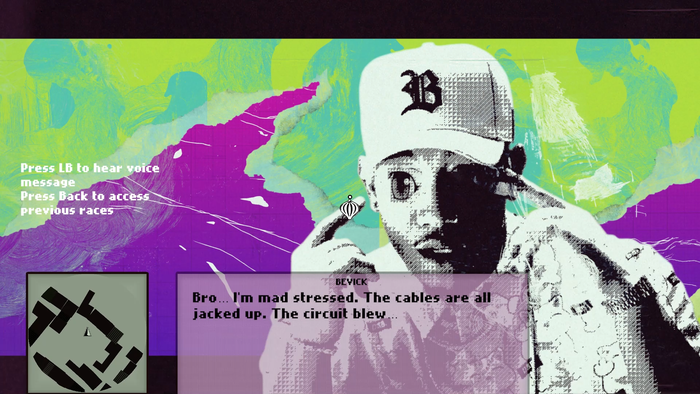

All the voices from baloeiros, musicians, visuals—are an expression of this. Dj Gordinho is the local deejay in the favela, Rocinha, and he provided most of the upbeat baile funk in the best Rio style. Bevick is an artist from Sao Paulo who mixes different styles of baile funk and rap. His flow was a bit different, so we gave him another area in the favela map. Gui, who did the acting of the brother, also had some rap tracks he wanted to get out, so we put them in a more chill area.

Like the balloons are tributes to other artists, friends, family members, I try to do the same with everything I do.

Sometimes it’s totally illogical. But I think it makes the process and collaboration more rich for everyone. Like working with some friends in Cuba who have a studio, Sindicato Havana. They made all the 2D graphics.

In terms of the art style; we wanted to reflect the balloon world aesthetics, which is a strange mix of beautiful colors, folklore, pop culture, and biblical iconography. No one can really put a finger on exactly what the aesthetic rules are, which is what makes it even more intriguing. It’s always a little surprising. To build the world, we used visual that resembled some of the earlier GTA games to give an illusion of a somewhat “recognizable world,” but with a different twist.

In contrary to GTA, you are never giving the opportunity to be violent. Yes, the world is violent, and you have to watch out just like in real life. However, that doesn’t mean that you as the baloeiro ever pick up a gun. It was important for us to counter the image the Brazilian media have condemned the baloeiros with.

What do you hope to evoke in the player by sharing this art style with them?

Dargis: For many, the balloon art seems irrational, incomprehensible. But baloeiros are just artists who have created a game around their art. Every balloon is a new adventure a new dream. I hope people will feel enough curiosity to support our next version of this game.

This game, an IGF 2022 finalist, is featured as part of the IGF Awards ceremony, taking place at the Game Developers Conference on Wednesday, March 23 (with a simultaneous broadcast on GDC Twitch).

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2022You May Also Like