Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

"If you give players too much information, the game design isn't challenging, and just becomes an operation they do as you prod them."

One of the biggest emotional problems for game designers of single player experiences is when players don't finish your game, says Suehiro Hidetaka, also known as Swery. Speaking at Nasscom GDC in Hyderabad, India, he says to do this, "you need to make sure players don't get bored with your games."

Back in the '90s, when working on arcade games, Swery says he "took care of how I defeat players, and how I can make them unable to complete the game. Because at that time, the business model and user demographic was different."

"With arcade games in particular, the business model is one point, one play. Basically you want them to continue as much as possible, which increases revenue. The most important thing was how you make them unable to finish."

Now though, as games get bigger, the number of games players actually finish has decreased without us noticing. The initial concept for the last game Swery directed, D4, was "100 percent of players will reach an ending."

Although 100 percent of players didn't actually finish the game, the completion percentage was very high for Season 1. Unfortunately, due to no longer working at D4 developer Access Games, he can't say exactly how high.

One of the things he believes will keep players pulling through is a compelling narrative; one which focuses on making a world, not a "story." That's because a game world-focused narrative lets players move around of their own free will.

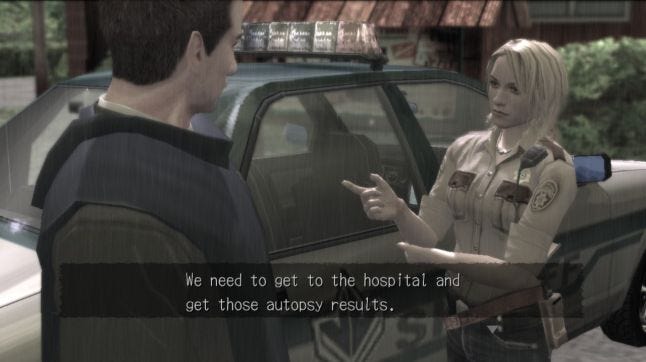

"With Deadly Premonition, there was game design at first -- players chase a murder case in an open world,” explains Swery, before outlining the creation process. "In order to do research, the team visited a place similar to the town where the story is set. We took a lot of photos, and made interviews with a number of people. With that, the story started to take shape."

"From this we identified those factors which were essential to the town," he says, such as what kind of places there would be for story nodes, where you could buy items, and what sorts of things would happen there. For example. if there's a sawmill, what might take place there?

As the world becomes clear, Swery explains they looked to figure out who the residents would be. "We finished drawing a map, and I imagined looking at this map, with these interviews, the manager of the supermarket must be like this," he says. "Through this process, the game gradually got its life force."

After getting a sense of the townsfolk, they started to throw in an outline, and a premise. In Deadly Premonition, the premise is "a young woman's dead body was found in a country town in the U.S., and an urban FBI agent has been brought in to solve the crime."

Now, questions arise. Who is this woman? How does this affect the people who live there? Who did it? "Like this, we answer questions one after another," he says. "Now, the story can run itself."

"If you give players too much information, the game design isn't challenging, and just becomes an operation they do as you prod them."

A story isn't a series of bullet points, Swery continues, but a connected line. Jumping around from point to point is not a good way to create story. So how do you make people feel as though some dots are part of a connected line? Cliffhangers! "The car which the hero drives falls off a cliff, with an explosion. To be continued," he jokes.

But players may drop out after one of those story nodes, and quite often he found players would complete an assignment, see the results screen, and then drop out.

"With this approach, a player might quit the game at this time. That quitting might be forever," he says. "So I change the pace of the results screen, putting the next assignment before the results screen shows up." After watching the result, players will remember the task they just saw, so they'll continue to play the game.

"What are reasons why players stop playing?" he asks "Perhaps the story is boring, they don't have enough time, or some other title was released -- there are tons of reasons. One of the big reasons is they give up because they can't defeat some segment."

There are two main reasons he thinks this happens. Shortage of information, such as not knowing how to solve a puzzle, or difficulty, where players can't defeat enemies or can't act as they want.

"A shortage of information is a very difficult problem," he explains. "If you give players too much information, the game design isn't challenging, and just becomes an operation they do as you prod them. But many players tend to seek not for hints, but an answer. If they can't find it themselves, they just look for an answer on the web."

For core gamers, hints are just fine. But for more casual players, they may just give up. At the very least, Swery feels the destination should be clear, even if the process of getting there isn't. That way the player always has hope of finding a solution.

But he cautions against adding hints in every place players come to a deadlock during user tests. "We creators are always self-conceited, and are under the impression that players will understand whatever we put upon them."

When it comes to difficulty, you've got the same problem. What's appropriate difficulty? This depends on the abilities of each player. There's a big difference between someone playing video games for the first time, and the core gamer who plays online games every day.

Ultimately, he recommends tuning difficulty based on the player, not based on enemies or challenge. This is, he says, "because the player character is the center of game design, and embodies what the player is able to do. Everything else branches from that."

You May Also Like