Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

When the team at Failbetter Games decided to make a sequel to their survival roleplaying game, Sunless Sea, there were a few areas they highlighted for improvement. One being progression.

When the team at Failbetter Games decided to make a sequel to their survival roleplaying game, Sunless Sea, there were a few areas they highlighted for improvement. One being progression.

According to Chris Gardiner, the narrative director at Failbetter Games, a lot of players had given feedback that they had “wanted to like Sunless Sea more than they did”. But the game’s fiddly progression system and lack of tangible reward had stopped them from becoming more invested.

So, in response, Gardiner devised a new kind of progression system for the sequel, Sunless Skies, one based around the idea of facets.

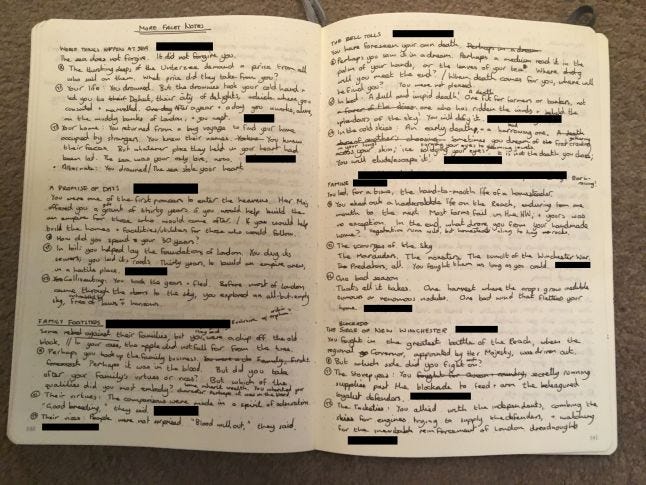

In Sunless Skies, players would be able to captain a locomotive and explore the unknown, being fed chunks of descriptive text, while trying to stay sane and stave off hunger. Yet, now, whenever they leveled up, they would be able to make a choice between a number of short narrative details about their past, called facets, that greatly increase one attribute while mildly improving on another (hearts, iron, mirrors, veils):

Hearts – “The skill of convincing and enduring”

Iron – “The skill of confronting and overpowering”

Mirrors – “The skill of investigating and deducing”

Veils – “The skill of deceiving and evading”

Some of these facets may be related to deeds the players themselves had accomplished, such as surviving after taking heavy damage to their hull; or expanded details about their past or their selected origins such as: street urchin, soldier, poet, academic, priest, zee captain, auditor, and revolutionary. The stats given from these could then be used by the player to pass skill checks..jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The inspiration for this concept came from a few different places, one of these being the character generation screens from Sunless Sea and Sunless Skies where you need to pick an origin and that then decides the stats you are going to be starting out with.

“My idea was to take that sort of choice and extend it throughout the character advancement,” says Gardiner. “So you’re not frontloading all the decisions about that character. You’re going to make those choices all throughout the game.”

In addition, Gardiner also took influence from several tabletop roleplaying games and their progression systems. A few which he calls to mind include Warhammer Fantasy Roleplay, where you can pick a career and increase your stats within that chosen area; Burning Wheel, which uses a system called lifepaths, that lets you follow a character through different roles; and Cubicle 7’s One Ring game, where advancement is unique to the specific culture you’ve chosen.

“It’s kind of a combination of all those things percolating in my head,” he says. “It goes back to this mantra of ‘let’s put story in it’. Wherever we could find an option to do it, we would put story into a mechanical system and add flavor to it that way. It opened a bunch of options to us. It became a good way to deliver more information about the world and the setting, which is baroque and complicated, and we [didn’t] want to bombard people with lots of stuff to begin with.”

When the decision was made to include facets as the reward for progression, another problem soon emerged. Mainly, how to make each decision feel impactful to your character, as given the sheer amount of options available not a lot of narrative consequence could be placed on any one decision. As Gardiner explains:

“[Facets] are really difficult to write […] because they have to be these really short, punchy initial situations, and then each of them has two little sub-choices attached to them. And both of those have to be meaningful in relation to each other. Choosing one over the other has to feel like a real decision because if you are one of them, you are not the other.”

To accomplish, Gardiner opted for broad strokes over specificity. This way they could introduce the player to a prompt, and then allow the player to use that as a way of contextualizing their own experiences and choose how they reflect on that.

“We have to leave a bunch of fruitful space for the player to fill in details,” says Gardiner. “So each of these can’t be too specific. So, for example, there’s one called ‘A Lost Love’, which is you’ve loved and you’ve lost and how does that affect you? We talked at one point about having a whole story about that where you could explore and kind of decide who it was that you’ve lost, and then kind of dig into that more. But in fact, it’s more useful for players to be able to decide that and make that part of their story.”

Already, the developers have seen this facet lead to some interesting stories emerging from the game’s community, given that they never explicitly state the identity of the lost love. Some players, for instance, have taken the facet and applied it in a way to create a relationship between their current captain and their previous one, while others have devised their own personal histories with some of the NPCs they’ve encountered in the skies. It also means players aren’t forced into heterosexual relationships and that they have the freedom to decide who they are.

As for the types of prompts they introduced, Gardiner took a thematic approach. Each batch of facets in the game had to relate to one strong, core theme, with the idea being to give them a sense of cohesion and grandeur.

“So, the first batch I wrote was all themed around menaces and bad things that had happened to you,” explains Gardiner. “And these were all taken from one of our other games, Fallen London our browser game. Death doesn’t happen there. But there are menaces that can happen to you, like scandal and wounds. And when those reach a certain point, you go into a menace state. Like you’re exiled or you’re imprisoned or whatever.”

Other batches included some facets related to individual origins, such as ‘An hour in Gethsemane’ where players that had picked the priest could decide whether or not they had lost their faith, and another based on the concept of the four horsemen of the apocalypse (death, famine, plague, and war).

“It was looking for big, kind of chunky themes that could support a range of different facets,” he says. “And that ended up making up a fairly diverse jigsaw.”

Facets weren’t the only change made to the progression in Sunless Skies, however. Pages, an attribute from Sunless Sea representing knowledge and trickery, was also taken out of the game. In Sunless Sea, players could use the pages attribute to earn more secrets, which could then be used to raise specific stats. But the conditions necessary to raise your pages were often vague and difficult to achieve. On top of this, there was also another problem.

“Anything that speeds up leveling up is a very powerful thing and it drastically affects how different players experience the game,” argues Gardiner. “So players are just going to get more powerful […] more quickly. And that’s very difficult to design around.”

The solution they came up with for this was to tear pages out and redistribute certain aspects of it into the other skills. For instance, military knowledge and tactics were moved to the iron stat, scientific knowledge shifted to mirrors, and knowledge of criminality switched to veils. This made the progression system slightly less complex for players to get their head around and also helped the developers keep parity between what skills were receiving the most attention.

As a result of these considerations, the progression system in Sunless Skies feels like a vast improvement on its predecessor. It constantly rewards the player with more details about their captain and offers incremental increases to their abilities, while giving them the room to interpret information in their own way. Gardiner, too, is proud of what he has achieved, but that hasn’t stopped him from worrying about what others will make of it.

“It was something that I was really happy with,” he says. “And I think that players have responded really well to it. It’s one of those things where you put a lot of time and thought into it and you’re never quite sure if any of that comes across.”

You May Also Like