Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Developer Brent Arnold talks about making just about every element in the game into a means of making endless (immoral?) profit.

The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry. Game Developer and GDC are sibling organizations under Informa Tech.

Final Profit: A Shop RPG is a game about making profits to fend off financial predators, and just about anything in the game world can be brought into your business if you’re savvy enough to use it.

Game Developer caught up with Brent Arnold, the game’s sole developer, to talk about the benefits and frustrating stigmas that come from making a game in RPG Maker, the importance of opening up every element of the game to be abused for the goal of maximum profits, and the moral questions that come from the game’s capitalistic goals.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Final Profit: A Shop RPG?

I'm Brent, the Australian solo indie dev who created Final Profit: A Shop RPG.

What's your background in making games?

Before going solo, I worked at an indie studio on the game Necrobarista as its cinematographer. I fell into the role accidentally out of university where I had studied animation and intended to go into film rather than games, but the job listing came my way and I applied for it using the 3D short film I'd made in my last year at university. They brought me in for a test and I got it. Before that, I'd done some pixel art commissions for small games, as well as the soundtrack and audio design for a mobile game that sadly no longer exists.

As a teenager I would make animated short films with friends that were all set in a world that has evolved into the one used in Final Profit. There are sneaky references to it that only a few people would recognize, but I hope to continue to expand this setting with further works and bring some of those old characters back into the foreground.

Images via Brent Arnold

How did you come up with the concept for Final Profit: A Shop RPG?

It started as a hobby project. Initially, I was just interested in building the basic shop mechanics, I think the itch pushing me to do so came from the shopkeeper minigame in Digimon World (PS1) I played as a kid. I took inspiration from other concepts in that game too like its level design/interconnectivity and having the game change and grow as you progress. But the minigame just served as thematic inspiration, as Final Profit plays completely differently.

I figured out what I liked and didn't like mechanically through experimentation, developing three prototypes before settling on how the core shop plays in Final Profit. Early on during the fourth iteration, I had some friends try it out and one of them said to me "Oh, this is actually good" and that's the moment I decided to pursue the project for real.

The 'critique of capitalism' element wasn't present in the first two prototypes, but as I was working on them, I was also researching how capitalism really works, not just at the meme level but really digging into it. Once that understanding was in place, I was able to build a world and story that is much more believable, with choices, conflicts, and consequences that can be a real challenge to the player’s morality. But the game also doesn't beat you over the head with the message. The depth is there if you want to dig in and think about it, or it can just be part of the background as you make that number go up.

What development tools were used to build your game?

My engine of choice is RPG Maker. I wanted to see if it could handle what I wanted to build and how far I could push it. Turns out it's capable of a lot more than I thought. Additionally, I composed over 30 original tracks for the game using KORGs iPolysix (love me some synth), as well as Gadget and REASON. And recorded over 150 unique voice sound effects that play as characters speak (Banjo-Kazooie and Undertale-style) using Audacity. When sprite edits or custom images were needed, I used Affinity Photo which is like Photoshop but without promising your firstborn to Adobe. And, of course, who could forget trusty old Notepad.

What drew you to work with RPG Maker on your project? What challenges and benefits did you find in working with it?

I've got a long history of hobby projects in RPG Maker, so part of the draw for me is how familiar I am with it, and therefore am able to bend it to do outrageous things. I do have experience in other engines (Unity, Godot, GameMaker) but I still really like RPG Maker for how quick and usable it is. Development speed is one of its great strengths.

One of the things fans of Final Profit often praise is how quickly I've been able to put out patches and respond if a bug pops up, sometimes getting a fix live in as little as 15-30 minutes. Also, having major content patches coming roughly once a month on top of that (although that has slowed down at the moment because the scale of the next patch is bigger than those that came previously). I've been going through and adding lighting to every map, which is a good place to pivot to speaking about the biggest challenge when working with RPG Maker: established bias against the engine.

The greatest hurdle that I continue to face is that the game looks like it was made in RPG Maker, and that turns some people off at a glance regardless of the quality. I've put a lot of care into every aspect of the game, including visuals, so it does sting when I see people dismiss it like that. The new lighting in the upcoming patch is intended to be another point of difference to that typical look. With my background in cinematography it's been easy to slide back into that role, but it's still a really big job.

The game has been up for 5 awards now and I keep wondering at what point will acclaim start to override that bias? I am still very happy with how the game has performed so far, but I know it's good enough to do better. There has been a noticeable boost of attention since the IGF nomination, so I'm hopeful that it will continue to gain awareness, and I'm very grateful towards the judges who gave the game a chance, as well as the dedicated fans who continue to help spread the word.

Images via Brent Arnold

Final Profit: A Shop RPG takes place in a world where almost anything—down to the people, the stock market, and the buildings—can become a part of your business. What thoughts went into designing a game world where almost every piece of it can be used by the player in some way?

Expanding beyond just being a shop into all kinds of different economic systems felt like a natural progression for the protagonist’s goal. In order to rise through the ranks of this capitalist structure, she should be exploiting the system everywhere and every way she can.

I spoke earlier about what influenced the shop side of things, but there was another major influence from the start and that was Fable 2 and 3's real estate system. I knew very early that I wanted to get to a point where I could implement something like that so I built towards it, not knowing if I would actually get there or how extensive it would be if I did. But one hazy evening after all the exterior maps were complete, I decided to commit and go hard, making every single on-screen property purchasable—an absurd and huge endeavor.

It also throws a curveball to the player quite late that changes the gameplay dramatically, though I hope they are somewhat accustomed to being surprised by new systems by that point as it's something the game will constantly pull on you. But real estate in particular is a very key (and cruel) part of capitalism, so I felt it was important to include. Alongside the stock market, these systems promote minimum effort for maximum profit, which is an ideal that is so addictive and desirable even though it causes so many issues in the structure of society, and I think the gameplay captures that quite well even though players may not notice without some introspection. But all these systems are mostly optional; it's up to the player to explore the world and experiment to find what works for them.

What challenges did you face in creating a world that was so interconnected? How did this outlook on the game world affect how you designed it?

Interconnectivity is something that I put a lot of care and effort into because I think it creates a much richer world and experience. I have an advantage when it comes to thinking this way through my autism, which allows me to hold a great deal of information at once and make broad connections with ready access. But on top of that, I keep extensive documentation. One of the lingering benefits from university is that it made me into an Excel/Sheets nerd, which has become critical for keeping on top of the complexity.

The game is interconnective in many ways through the systems, level design, worldbuilding, and story. The game systems often influence each other. This is most present in the shop which I try to tie everything back into—for example, how envelope sales affect the post stock price, or how commodity supply in the late game only refills based on other products sold. Another place this manifests is how most systems tend to improve or unlock additional features through engaging with them, such as how product quests unlock through sales, or how the cap on stock dividends can be doubled by filling it up. The general idea was to make it so that the more you used something, the better it would get for you—a kind of organic specialization.

For level design there's a similar ideal at play. Shortcuts unlock often through engaging with things in the area and they are placed in ways that make them more useful the more you unlock, with little mini-hubs emerging as the interconnectivity increases. This is sort of like bringing Metroidvania level design into an RPG. Eventually getting around becomes something of a minigame as you learn to plan your journey based on your map and shortcut knowledge.

For the worldbuilding and story, I try to keep track of what characters are up to offscreen, with things happening that the player isn't always involved with. Some players have been picking up on things in the game alluding to these events and making predictions about the sequel which has been fun to watch. The player's choices also have long-reaching consequences that affect how things develop as you progress, changing systems partially or sometimes entirely.

I'll lean on the envelope product and post stocks again for an example. After selling enough of the product, a quest becomes available where you can choose how you'll choose to support the post office financially. You can choose to reinvest your dividends in them which will lead to a steep increase in envelope sales much later on, or you can lower the sale price of your envelopes now to increase how many will be sold, accelerating how quickly their stock price goes up. Both options lead to very different streams of income, with other negatives and benefits attached to each that I won't spoil here.

You have mentioned that there were several prototypes before you settled on the format for Final Profit: A Shop RPG. Can you tell us a bit about the past versions and how they lead you to this one?

They were a way to explore shop mechanics, looking into what makes them engaging or if they would even work at all in the engine. The basic premise of a shop where you place items on a table and customers come to buy those items stayed throughout, but there were significant differences in the approach to that concept.

Originally there was an on-screen timer and when it ran down all customers would arrive. This was quite stressful, feeling beholden to the timer. So, in future, it was no longer visible and each customer would operate on their own timer, changing the feel from an ON/OFF dynamic to a constant flow of keeping on top of problems. The item selection on the table also started out letting you place any item anywhere rather than having set places for each type. This sounds good in theory, but quickly devolved into only placing the best item and nothing else. So, the change was made to keep the player invested in multiple things rather than putting all their effort in one place which would get boring quickly. I've since had ideas on how to make that work better in future games, but that's a discussion for another time.

The disappointment mechanic also started very differently. In the final game, it's something many players may not even notice but it makes customers visit less frequently if the items they want aren't available. This organically regulates customer frequency to what the player can handle, though it's quickly made irrelevant as automation is implemented. Originally the disappointment value was not on the customers, but on the player character. It still increased when customers didn't buy items, however its effect was to make the player slower. And to reduce it you had to keep a fire at the back of the store stocked with firewood.

I still like the idea of it affecting the player, but speed was not the way to go. It just became impossible to move and harder and harder to get more wood while also getting products. But there was another iteration on the disappointment mechanic where the greater it became, the further you could venture into a maze where you would unlock new products and space to grow things. That concept developed into what the Apple Maze became, giving the Apple collectables found throughout the game a use as they originally did nothing. But now, not only do they grant access to the maze, they also unlock the Apple Treasure Chests which function like the Silver Key Chests found in the Fable series. And a bunch of Apple themed lore has sprung up around it too, it's become an integral part of the setting.

Customers also worked differently originally. Instead of having a set list of items that they will or won't buy, they would make purchases at random because it was frustrating to get a bad streak of no sales. I realized that the things that I found fun and engaging about the shop loop was predictability. If you know what an item is worth and who will buy it, you can make more interesting decisions than if things are just flying off the shelf willy-nilly.

The story also changed over these iterations. Originally, you played as a character called Vend who had inherited a shop and a debt. They were working to pay it off but weren't really sure if it was what they wanted to be doing. That one was quite short with multiple endings you could reach quickly—my favorite being just walking out of town and deciding that it wasn't at all what she wanted to do (in Final Profit as an easter egg Vend is the NPC who owned the Enterpriston store before we arrive on the scene, once again having decided that shop life isn't for her).

But Biz (the protagonist) did emerge shortly after that, as did the idea of a hidden Fae kingdom being encroached upon by a capitalist society called Industria. She'd begin the game with the full support of her kingdom, but no one there knew anything about capitalism so you were going in without knowing what you were doing, with Fae showing up intermittently with ways to help out. Eventually I dropped the idea of the Fae being a hidden society because it made the political situation more interesting. Industria was scrapped in favor of a corporate entity called the Bureau of Business. Originally, Biz was going to lose the support of her people gradually as she became corrupted by business, but I think it played out better having the story open with that story beat instead, starting with nothing and having to gradually earn back support.

There was also originally turn-based RPG combat as it felt like a mandatory thing to include in an RPG, but it was used sparingly. To automate a product, Biz would lure the product vendor out to a Fae ritual site where she could use her power to awaken the corrupt aspects of the vendor, they would turn into a monster, and by beating it you'd complete the automation requirements and learn a new combat spell. There was also a group of adventure customers that Biz could outfit and go on expeditions with to fight monsters for quest specific reasons. But it all felt very dissonant to the shop side of things and the idea of fighting capitalism from the inside, so it was scrapped entirely. I think for the better.

Images via Brent Arnold

There are many compelling shop-management games out on the market. How did you work to make sure yours felt unique? What ideas were core to making this something special for you, as a developer?

It often surprises people to hear that I hadn't actually played Recettear when I began development seeing as that's what people usually refer to first when looking for a comparison, but Final Profit is quite unique in the way it brings so many different things together (and that makes it really hard to tag on Steam!). I did check Recettear out halfway through development and found some surprising connections, but they are coincidental.

I didn't set out to compare against or draw from any other shop game; I simply made what I would enjoy—the core of which would be the predictable customer/product interactions rather than RNG-based ones. The exclusion of a time system (because I find them stressful and artificially limiting), which allows the player their freedom to pursue whatever activity they feel like in the moment. The constant progression of systems—building upon what you have to reach further while automating away the stresses it took to get where you are. A dense/detailed world to explore filled with secrets. And, of course, the story, world, and underlying themes exploring the issues that arise under capitalism.

What thoughts went into designing progression and stats around running a shop? How did you create progression outside of purely making more money?

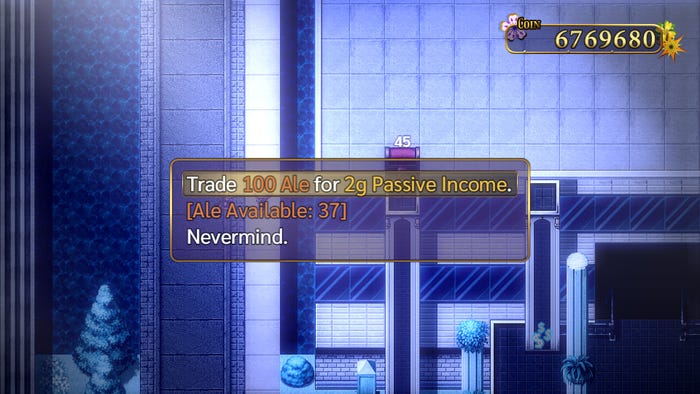

For ideas on how to approach progression, I looked to clicker type games. I was having a good time with Cookie Clicker at the time and took inspiration from there. But I didn't want Final Profit to just be an idle game—those elements are present and make it possible to play in a less active way, particularly in the endgame once the passive income system becomes available, but doing so is not optimal. I put a lot of care into adding compelling play options to keep the shop engaging once all the products become automated. These gradually unlock at times aimed to fill those action gaps as you progress.

There's also a lot of RPG elements targeting progression as well like levels, stats, equipment, spells, items, and quests. Equipment was actually a very late addition, only getting added in the final months of development. I felt the game needed more customization options and they provided an avenue for players to spec into specific playstyles, as well as giving me an option for impactful rewards to divvy out among the puzzles and secrets of the game. Most systems also have upgrades and tiers of improvement, usually unlocked by engaging with those systems or by spending sizable chunks of coin which serves to keep the amount of cash the player has on-hand in check while simultaneously giving them a permanent improvement to how much they can generate going forward. All of this together is a complex, messy web, and is very difficult to balance around the central thing they all impact: coin, the game's currency.

Since making money is the main thing you're doing most of the game, it's very important to balance the rate of income vs expenses while also keeping in mind how much upgrades should cost at different points of progression. The way I managed to keep on top of balance is through rigorous testing, playing through from the start over and over constantly to see how much money players would have at any given time and how changes would affect that at different stages. I'm very lucky to have a few friends who were willing to do playtesting as well. Playtesting is also how I anticipate the quality of life needs of the player. Many systems start out taking a bit of work, and just as that starts to feel like too much, the game will offer a way to ease the burden. Even now, I still watch carefully when players stream the game or put out videos to keep on top of any pain points that need improvement.

Automation is a useful part of the business process in Final Profit: A Shop RPG. What ideas went into the game's automation systems? What drew you to let players automate certain things to save time for finding more ways to make money?

I realized early in the prototyping phase that even the simple task of keeping products on the table became nearly impossible to keep on top of as more things to manage kept unlocking. So, I decided that automation would be necessary if I wanted to keep expanding the complexity of the game. But it was too powerful to give instant speed automation straight away, although I still wanted it to be available immediately.

Since the player wouldn't have high amounts of coin in the beginning to afford something so strong, I split it into a tiered system where you can get slow automation fairly cheaply, and then pay more later to improve it. This keeps manual table management relevant in the early stages when customers are coming in faster than slow automation can handle, especially with those that buy a lot of one thing such as the bees with the first drink item. And it's especially important for keeping everyone's favorite customer Magnolia (the chicken) happy (and who really begins to shine as everything reaches tier 2 automation). I wanted players to learn a task, master it, and then be able to put it behind them to learn and master the next thing, each time building upon your earning potential and opening new possibilities.

Since automation is such a key part of the game, I had to make sure that players would encounter it quickly. You get a taster in Tutetown with the basic automation pillar after selling 15 hats, which also serves as a way to encourage players to leave the shop to get Mana and hopefully explore on the way. There's a lot of things happening in Tutetown to encourage exploration outside the shop, as an early pitfall I noticed was that people would sit in there selling the two items obtainable inside and not realize that there is so much more to the game. And then, once you reach Enterpriston getting that first automation pillar set up is mandatory to progress. I prefer to not use such railroad-y tactics in my design, but it was too important an element to leave for the player to find (or not) on their own, especially with how much the exploration options expand at that stage.

With such a focus on making profits, what thoughts went into the morality system in the game? What feelings and consequences did you want to touch upon in the protagonist's journey to collect wealth to save them from financial predators?

Rather than the typical karma stats of Good and Evil, Final Profit uses Generosity and Ruthlessness. The difference is very intentional because choices are not always 1 to 1 good vs bad. Instead, these stats are rewarded based on Biz's intentions when making decisions. But her goal is still to profit either way, which is inherently exploitative because it involves extracting more value from someone in a transaction than what you offer in return. It's my hope that by immersing the player in this system that it may prompt them to think about how much of the inequality and unethical practices that arise under capitalism are actively encouraged by this reward structure.

I also wanted the choices themselves to be more important than the karma system. They have far-reaching consequences that change elements of gameplay and affect the story way down the road. The point isn't to stick to one side or the other; it's to really think about what you're doing and how it will affect you and others. So, there are no checks present asking you to have a certain amount of Generosity or Ruthlessness because that would incentivize piling mindlessly into 1 stat. The game does however care which one is higher, and there is an early choice that breaks this ideal because it will only appear if you have 0 Ruthlessness. That is present simply to make a 0 Ruthlessness run possible because I know some players want to play that way, and even though it's not my intended way to play, it's still something I want to accommodate.

Biz's actions and even goals are not always morally sound. She wants to save her people but is quite happy to exploit the humans to do it, and by time she gains enough influence to have a hand in her own people's affairs again she (and the player) have become so focused on profit that they're willing to exploit them, too. Because making a number go up is addictive, it's true in a video game and it's true in our economic system. But there are other characters with very different ideals actively working towards their own goals. Again I'm not trying to portray any of them as correct. I’m just demonstrating their points of view and actions.

When I began writing the story I envisioned a certain ending, but that's not where Biz's journey took me. Instead, we end with a very volatile situation that is going to be tough to handle, both for the characters involved and for me when I start work on the sequel.

You May Also Like