Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Many games reward the player for using its systems properly by allowing them to progress. If you learn how to play the game well, you move on through the game's narrative to greater challenges. Pony Island is different.

Many games reward the player for using its systems properly by allowing them to progress. If you learn how to play the game well, you move on through the game's narrative to greater challenges. Pony Island is different. It arguably rewards the player for doing something they're not supposed to be doing: manipulating and breaking the game's code.

The game looks like the sort of straightforward and kid-friendly experience you'd expect from something called Pony Island. But players soon discover that a demonic spirit hides in the guts of the game's code, and the only way to exorcize it is to penetrate the game's cute exterior and hack away at its properties. Its multilayered gameplay and dark humor are earning it raves.

"I was always intrigued by the idea of poking around at something dark and mysterious, and I like the feeling of playing something that feels like I wasn't supposed to play it." says Dan Mullins, developer of Pony Island. His vision for Pony Island involved a game that desperately doesn't want players to be able to complete it.

Accomplishing that, from both a gameplay and narrative perspective, would not be easy. How do you establish a mood where the player feels that the game itself is antagonizing them? How do you instruct the player on the proper way to play the game, when playing the game properly requires you to break the game and mess around with its code? How do you make players feel like they're doing something they're not supposed to be doing... when it's actually precisely what they're supposed to be doing?

Crafting that dichotomy started with giving no instructions during the phases where the player was altering the code of Pony Island. It had to be something the player figured out on their own.

This didn't mean that Mullins couldn't hint at what to do through the visuals. "One of the ways I make a puzzle intuitive and understandable is by tapping into knowledge the player already has." says Mullins.

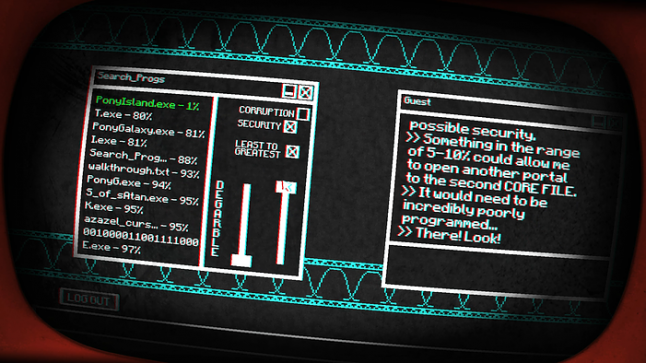

When you suddenly find yourself staring at a list of strange commands after all you've been previously doing was pretending to be a pony jumping over fences, it can be daunting and confusing. What do you do with these lines of words? Where do you want the cursor to go?

Players come to your game with a certain knowledge base already in-place. This can be something as simple as knowing that keys open things, or that double-clicking an icon on a PC will run a program. Not exactly life-changing knowledge, but for Mullins, those items could be used to teach the player about the game's coding world without having to come out and tell them how it worked.

"There was a long period of time in which the coding puzzles did not have the key and keyhole images," says Mullins. "Instead, the key was just a triangular pointer and the goal line was just a different color." Players didn't understand the puzzle system because they didn't understand what their goal was.

"When I realized this, I tried adding images that made the goal intuitive--'Fit the key in the slot' is so much easier to understand than, 'make the triangle point at the different colored line,'" he says.

Most players, even young ones, would know that keys go in keyholes. It's a kind of universal knowledge that would transcend language and culture as well, providing a clue to any player on what to do just from looking at the screen. "It sounds obvious in hindsight, but some problems like this refuse to present themselves until you watch someone else play your game." says Mullins.

With clear visual communication, he still just had a bunch of code on a screen. What else could he do with this segment to make it feel vaguely menacing uncomfortable for the player? Part of the process involved adding nebulous, unknown text in the coding segments.

"I think the lines of text in these puzzles being very difficult to read while still providing some notion of their meaning added a lot to this effect. When you don't fully understand all the text, you aren't entirely sure what the effects of your tampering will be. I think that contributes to the feeling of uneasiness." says Mullins.

"I think the lines of text in these puzzles being very difficult to read while still providing some notion of their meaning added a lot to this effect. When you don't fully understand all the text, you aren't entirely sure what the effects of your tampering will be. I think that contributes to the feeling of uneasiness." says Mullins.

This taps into some fears computer owners likely have. Even a savvy computer owner has, at some point, gotten into an area of their operating system that they didn't understand. Many of us have accidentally or purposely deleted or altered some key file, named in some incomprehensible (to us) way, and unwittingly caused catastrophic damage.

That is a simple, but common, fear. Pony Island's unsettling mood comes less from making the player fear the evil force in the code, but more about whether they're doing damage to their computer or the game itself. The code looks real enough that it creates a worry that maybe you are doing something you shouldn't be. It plants seeds of real fears in the player.

"This feeling of being somewhere that you shouldn't be and toying with a system that you may not fully understand is unsettling." says Mullins. The player understands enough of what is going on, again by bringing in the (possibly limited) knowledge of computers they would have to possess to turn the game on, and that knowledge is used against them feel nervous. Are you truly sure you're just playing a game? That strange words on screen look vaguely reminiscent of what you saw that time you screwed up your registry.

Mullins didn't stop there. Pony Island layers on levels of meta on top of the gameplay. There are faked crashes, error sounds, Steam friend messages, and other unexpected intrusions that we won't spoil here. It seems to reach out beyond the confines of the game itself and start messing with things in your computer, or in other programs.

"A big part of Pony Island is taking your expectations about how a game should work and flipping them." says Mullins. "The fake game crash and fake Steam messages were just more ways to surprise the player by doing things they would never expect a game to do. I think these elements were important in creating an uneasiness about what would happen next."

Through careful planning and shrew leveraging of common points of reference, Mullins crafted a game that taught the player what to do while simultaneously creating a mood that made the player unsure of their every action. He was able to create a terrible fear in a game about keeping pretty ponies from tripping over fences.

You May Also Like