Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

CD Projekt Red's Damien Monnier and Rafal Jaki explain the background of The Witcher 3's collectible card game Gwent.

Last year’s The Witcher 3 gave players the opportunity to travel the Northern Kingdoms, slay monsters, delve into politics…and ask nearly every single person on the continent if they would like to play a round of Gwent. At this year’s PAX East, unofficial Gwent leads Damien Monnier and Rafal Jaki of CD Projekt Red gave a presentation (starting at on how the game-within-a-game came to life.

Gwent, for the uninitiated, is a deckbuilding card game within The Witcher 3 that lets players buy, steal, and compete for rare cards around the entire game world, facing off with major story characters and random shopkeeps alike. It’s a feature that won a lot of praise from players shortly after release thanks to its surprising depth and its presence both as an unconventional quest reward and occassional quest driver.

Its origins, however, weren’t nearly as grand as its reception. Monnier, a senior gameplay designer at CD Projekt Red, and Jaki, who works in business development, began their work as fans of tabletop games who thought having one in The Witcher 3 would help improve the game. Minigames like dice poker and arm wrestling had been present in the previous two entries, and the pair also felt that minigames like Gwent provide non-combat ways for players to relax and add new layers to characters in the game.

They’d begun by soliciting card game ideas from outside developers, but found that none of the results were satisfactory for studio owner Adam Kiciński. At the last minute, they petitioned Kiciński to let them try to make their own card game, to which he replied “you have three days to make it.”

“We came out of the room, both smiling, and literally looked at each other and we were crying inside,” says Monnier.

“He wasn’t trying to be cruel,” Jaki clarified, “we were occupied with our own tasks on the Witcher team, and he wouldn’t want to waste more time pursuing something that wasn’t going to happen.”

After a long weekend of hashing out possible game ideas, and reaching for inspiration from games like War, Netrunner, and Condotierre, the pair arrived at a working demo that would ultimately get the sign-off from Kiciński.

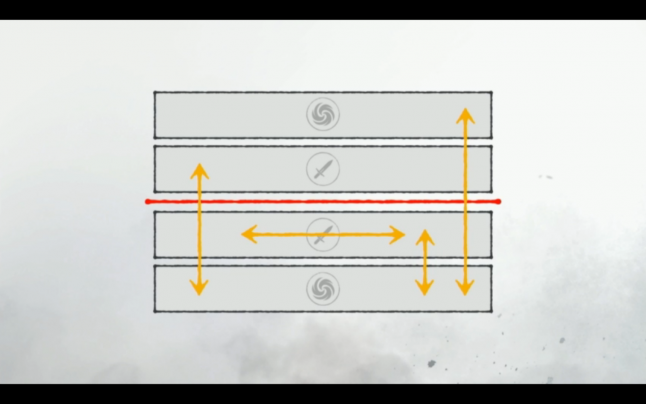

Monnier shared some of his diagrams representing early builds of Gwent, and how the game’s flow ultimately drilled down to the placement and movement of cards. One early version, seen below, shows how a version of ‘soldiers and mages’ didn’t work because mages assisting a players’ own soldiers conflicted visually with attacking soldiers on the other team.

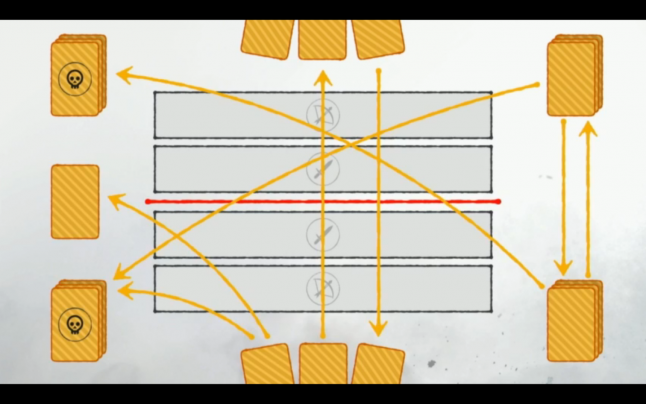

The final version, closer to the diagram below, kept the game neatly organized along vertical lines, and gave players clear direction for where cards would come from and where they could go, helping Monnier and Jaki realize it was more fun to place cards on the other side of the board for price then manipulating too many variables on a player’s own side.

There was one major cut to Gwent during this timeframe, as Jaki explained. “You never steal cards from your opponent’s hand. If you play a card and I steal it, maybe that’s punishment for a bad play, but if I steal it from your hand, it’s unfair.”

There was one major cut to Gwent during this timeframe, as Jaki explained. “You never steal cards from your opponent’s hand. If you play a card and I steal it, maybe that’s punishment for a bad play, but if I steal it from your hand, it’s unfair.”

From here, Monnier and Jaki explained that even with Kiciński's approval, Gwent still needed an ad-hoc team of developers, artists, and writers from across the studio to bring it to life. Instead of lobbying producers however, they built a development team by luring officemates into games of Gwent and inviting them to help develop if they thought was cool.

Ultimately, the pair assembled interdisciplinary team where translators, marketing artists, and programmers stepped outside their traditional roles and helped bring the game to life.

Gwent’s inception as a side-project from passionate developers does showcase the promise of how pet projects can influence a larger AAA game. And for readers looking for a similar opportunity in their studio, it’s a lesson in considering what other skillsets their colleagues might possess outside of their job titles.

You May Also Like