Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The colorful dev Jeff Minter and the Llamasoft team transposed their trademark shooter style into VR for their latest title Polybius, without sacrificing quality or giving the player motion sickness.

Working in virtual reality poses a number of interesting problems that aren’t found anywhere else in games development. For the veteran development studio Llamasoft (Space Giraffe, Tempest 2000), this was how to transpose its trademark arcade style of gameplay into VR for its PlayStation VR title Polybius, without sacrificing on quality or giving the player motion sickness.

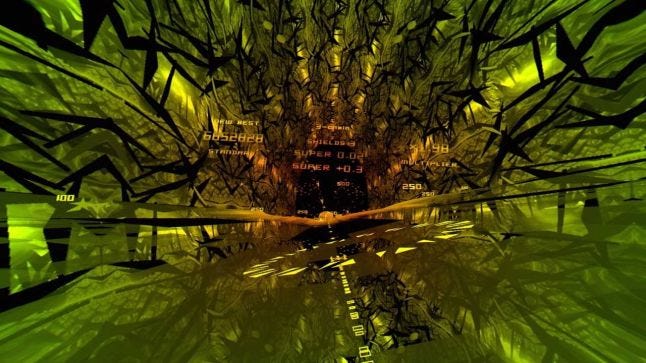

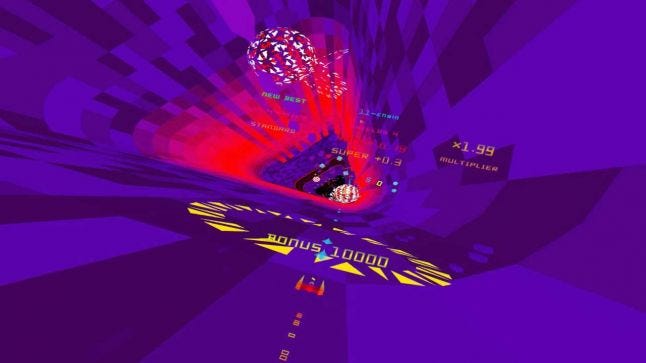

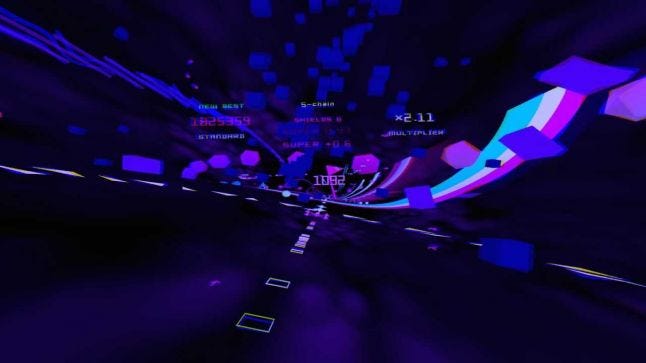

In Polybius, which launched earlier this year, you control a spaceship hurtling down a long tunnel. The aim is to shoot the obstacles that appear in your way, as well as boost your speed by moving through gates littered across the level. The more things you destroy, the higher your overall score will be. The real star are the distinctive visuals.

Distinctive is an understatement. Its look is so unique that Trent Reznor cold-called Llamasoft to ask if he could use footage of the game in a Nine Inch Nails video.

But even the compulsively watchable music video, which was made using a special PC build of the game with a configurable effects sequencer, doesn't capture the sensory overload of playing the game in VR.

To make this frenetic shooter work in virtual reality, Llamasoft used its own engine to get the most of the PlayStation VR’s native 120Hz display, and kept the focus in one direction to prevent the player from becoming disorientated. The final product may well be Minter's most successful stab at VR, which he's been experimenting with for over 25 years.

"I’d heard about the Polybius urban legend for years. I thought it’d be quite nice to do some VR game based on my own idea of what Polybius might have been like. But, obviously, instead of trying to make it harmfully addictive, I aimed to make something that would make you feel good."

It’s important to note Polybius wasn’t Jeff Minter’s first experiment in VR. It was in the early ’90s that Llamasoft’s founder first started messing around with the technology, borrowing a dev kit from his friends in the industry.

His first project in VR wouldn’t be until much later, however, when he decided to reimagine his popular mobile game Minotaur Rescue for Oculus Rift, Samsung Gear VR, and the prototype PSVR. This was followed soon after by a doomed VR adaptation of TxK – a game that was unfortunately shut down by Atari, the original publishers of Tempest 2000, for issues with copyright.

After TxK VR was cancelled, Minter found himself back at the drawing board, and so started spit balling ideas for a new PSVR title. It was then that he found inspiration from an unusual source -- the urban legend of Polybius, a mythical black arcade cabinet that was said to have caused a string of deaths in the early 1980s.

“I’d heard about the Polybius urban legend for years and years. I thought it’d be quite nice to do some virtual reality game based on my own idea of what Polybius might have been like," he says. "But, obviously, instead of trying to make it harmfully addictive, I aimed to make something that would make you feel good instead of end up damaged by it.”

"There was a meeting with Sony and I was supposed to show first playable and I didn’t have anything."

Though he had the general idea for the game, Minter was still having difficulty defining the central gameplay hook that would keep players coming back for more. This was something he found himself agonizing over.

“I knew I was going to do something where you were flying forward over a surface. And I was trying this and I was trying that and I found that six months had gone by and I still didn’t have a game.” He recalls, “There was a meeting with Sony and I was supposed to show first playable and I didn’t have anything.”

Minter eventually devised a rough prototype with a spaceship flying over a flat surface. But it wasn’t until he came up with the idea of little gates that would increase the player’s speed that he had a breakthrough. This would come to form the basis of the game.

"VR is very demanding. A lot of early PSVR stuff used a fairly low-resolution memory target, which meant that it tended to look quite grainy. And a lot of the earlier stuff didn’t actually hit 120FPS, which we can. "

The energetic gameplay came with its own set of challenges. One of the most pressing was how to make it appear as smooth as possible on the display. To accomplish this, the team at Llamasoft opted to use their own engine, and optimized the code to maintain an extremely high frame rate.

“VR is very demanding," Minter says. "A lot of early PSVR stuff used a fairly low-resolution memory target, which meant that it tended to look quite grainy. And a lot of the earlier stuff didn’t actually hit 120FPS, which we can. That makes it look really solid and really nice.”

The person responsible for Llamasoft’s robust engine is Minter’s partner, Ivan ‘Giles’ Zorzin. His expert coding allows the game to maintain that high frame rate, which lends the hallucinatorily intense VR experience an almost eerie level of clarity. “The fact that we’re able to hit such performances levels on the PSVR was all down to his hard work,” says Minter.

“It’s quite funny, because I remember we went to one of the first PSVR dev cons and they were explaining the various different modes it runs in and said, 'Here’s the 120 Hz native mode.'" he recalls. "The guy said, 'Look, hardly anyone is going to use that, because it’s really difficult to get it to work well', and Giles said, 'Well, we’re going to use it.' He worked his butt off to make that work.”

"That was something that I really wanted to do, to give you a speed rush without giving you nausea."

Another important issue they had to overcome was how to give the player a sense of speed without making them experiencing motion sickness. The 120fps gameplay arguably helped with this. But Llamasoft also came up with several other solutions to decrease the chances of this happening.

“That was something that I really wanted to do, to give you a speed rush without giving you nausea.” He adds, “It seems to me it was quite simple. We keep your attention focused way off into the distance, so you’re not looking around all the time. Secondly, we avoided any kind of yawing, rolls, or any kind of excessive change of acceleration.”

It did the trick. The result is an experience that feels exhilarating to play, but not nauseating.

"I looked up and there’s a giant pair of testicles up above me."

There were also some unforeseen problems with coding for VR. Unsurprisingly, they involved ruminants.

As in many of his other games, Minter decided to add ruminants to Polybius, decorating the sides of the stages with bull. His first attempts at incorporating this into the VR version, though, though, didn’t go according to plan.

“We’d written this code to import the bull model into VR. When we first put it in, I went to check it out and I thought, 'I got it wrong. I can’t see the bull.' Then I looked up and there’s a giant pair of testicles up above me. The bull was on the ceiling.”

Polybius very much feels like a Llamasoft game. It’s an extremely streamlined arcade experience, with psychedelic visuals. And cows. As for the future, Minter seems excited about continuing to work in VR, and this shows in his plans.

“We’re going to finish Tempest 4000 [fruit of his reconciliation with Atari] before Christmas," he says. "Then we’re going to finish the PC version of Polybius and get it out next year. After that I want to go back into VR and do more stuff. I’ve got some ideas and I want to schedule time to work on them, get down to prototyping, and go from there.”

You May Also Like